Alexej von Jawlensky among his friends at Warmer Damm, Wiesbaden 1924. Photo: Private Archive Kirchhoff, Estate Mieze Binsack

‘They’re already expecting me in Wiesbaden,’

wrote Alexej Jawlensky to a friend in Zurich on 31 May 1921.

With the opening of the centenary exhibition The Lot! 100 Years of Jawlensky in Wiesbaden, Museum Wiesbaden and its partners wish to bring stories about the artist out into the city. Stay tuned and follow Alexej von Jawlensky's footsteps!

Wiesbaden Main Station

1. June 1921 – Jawlensky arrives:

‘They’re already expecting me in Wiesbaden,’ wrote Alexej Jawlensky to a friend in Zurich on 31 May 1921. The painter was sitting at the Badischer Bahnhof in Basel, waiting for the night train to Wiesbaden. The success of his exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden that spring had put the city on his map. The next day he arrived at the main station and received such a warm welcome that he soon decided to settle down there for good. The famous Expressionist painter, who had been a member of the artist group Der Blaue Reiter, would live at Nikolasstrasse 3 (today Bahnhofstrasse 25) until 1928. He then moved to Beethovenstrasse 9, becoming a neighbour of his patron Heinrich Kirchhoff. The local museum, today home to the most significant Jawlensky collection in the world, frequently exhibited the painter’s work during his lifetime. Jawlensky quickly felt at home in Wiesbaden—in part thanks to the large Russian Orthodox community, which has been here since the first half of the 19th century.

Adress:

Hauptbahnhof Wiesbaden

Mobilitätsinfo von ESWE Verkehr

Bussteig A

65189 Wiesbaden

Mela Escherich: the art historian and the artist

In 1922 Alexej von Jawlensky and his family moved into a flat at Nikolasstrasse 3 III, today Bahnhofstrasse 25. The art historian Mela Escherich had lived in the street for nearly twenty years, at house number 22 IV (today 40), located directly in front of you. Having completed a doctorate in art history, Escherich reviewed local contemporary art exhibitions for a variety of newspapers and journals, including Nassovia, Cicerone, the Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, and even the Wiesbadener Tagblatt. After Jawlensky moved to Wiesbaden, his art—and above all the series of ‘abstract heads’ that he developed here—became the focus of Escherich’s writing. Both the art historian and the artist were fascinated by the aesthetics of the mythic, and until Jawlensky’s death in 1941 they maintained a professional and cordial relationship, which remained unbroken even when the Nazis labelled him a ‘degenerate artist’. Knowing this, in 1946 the post-war museum director Clemens Weiler hired Escherich as a research assistant. She energetically supported the scholarly reappraisal of Jawlensky’s work, thus making a significant contribution to embedding the artist in the city’s cultural memory.

Adress:

Bahnhofstraße 40

65185 Wiesbaden

A new home in the best neighborhood

Back to Germany it would go – to Wiesbaden, to be precise, because there the people had been struck with “Jawlensky mania, ” as the artist’s agent proudly described it in the wake of the artist's markedly successful exhibition in the New Museum Wiesbaden. So, it was decided: The expressionist artist Alexej von Jawlensky moved to the spa town in 1921, where his family was to follow him in 1922. The Jawlenskys moved into their first shared apartment in Bahnhofstraße 25 (then, Nikolasstraße 3 III), an illustrious neighborhood: Not only was the Hansa Hotel a small architectural gem of its time, but its restaurant was also to become one of Jawlensky's favorite spots and, in turn, a gathering place for the avant-garde around the artistic circle of Otto Ritschl, Edmund Fabry and art patron Heinrich Kirchhoff. One can only imagine the plans that were forged here over a few glasses of wine and how much such a place must have meant to Jawlensky, who after all his years in exile in Switzerland not only found a home here again, but was even courted by the local art scene, no doubt to his great delight.

Adress:

Star-Apart Hansa Hotel

Bahnhofstraße 23

65185 Wiesbaden

Helene steps in!

Susanne’s Beauty Institute

In the late 1920s Jawlensky’s painting sales notably declined. On the one hand, this was due to the world economic crisis, which had severely impacted even wealthy patrons like Heinrich Kirchhoff. But it was also the effect of the emergent new cultural policies of the Nazis. To ease the family’s financial difficulties, Helene von Jawlensky trained as a make-up artist in Paris, and in the summer of 1928 opened ‘Susanne’s Beauty Institute’ diagonally across from the Museum Wiesbaden. On 15 January 1929 Jawlensky wrote to Erich Scheyer, the brother of Galka Scheyer, who represented the artist in the United States: ‘Helene works diligently in her salon, to great success.’ But on 17 February 1932, he told Galka that ‘Helene no longer has her institute.’ The beauty salon thus lasted just under four years. It is possible that she stopped working to tend to Jawlensky, who had become visibly sicker and required daily care.

Adress:

Hedegger GmbH & Co. KG

Wilhelmstraße 2–4

65185 Wiesbaden

The museum, the city, and the artist

The fact that Museum Wiesbaden today has one of the most comprehensive collections of Alexej von Jawlensky’s art is not only due to the artist having lived here for the last 20 years of his life. It is, above all, the merit of Wiesbaden residents who, for years, dedicated their lives in numerous ways to art and promoted Jawlensky’s artistic work throughout his life and after his death – making Museum Wiesbaden, by and large, the pivotal point of their activity. Today, Jawlensky is the namesake of a school, a bus stop, a street, and, finally, an art prize that extends his reach far beyond the museum itself. His fresh start in Wiesbaden, his new home, his circles, and the stories of his companions are told, now, through the museum’s extensive Jawlensky collection and can be experienced at the original locations on the Jawlensky Trail. You can start your Jawlensky discovery tour right here at Museum Wiesbaden!

Adress:

Museum Wiesbaden

Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 2

65185 Wiesbaden

Jawlensky’s second apartment in Wiesbaden

On 1 May 1928 Alexej von Jawlensky moved to Beethovenstrasse 9, together with his wife Helene and their son Andreas. The proximity to his patron Heinrich Kirchhoff, who lived at Beethovenstrasse 10, was perhaps a decisive factor for their relocation. Jawlensky died in his apartment on 15 March 1941. Four years later, on 2 February 1945, Allied forces bombed the building. Helene von Jawlensky survived and was able to save most of Jawlensky’s works, which were stored in the basement. Käthe Henkell, widow of the champagne manufacturer Otto Henkell (d. 1929), lived nearby at Beethovenstrasse 5. She sent her gardener over with a wheelbarrow to collect the paintings—a remarkably courageous move in a time when Expressionist art was considered ‘degenerate’. The current Jawlensky exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden presents the reverse of the painting Blue Mountains: the burn marks from this horrendous event are still visible.

Adress:

Beethovenstraße 9

65189 Wiesbaden

Jawlensky’s patron: Heinrich Kirchhoff

The art collector and avid gardener Heinrich Kirchhoff (1874–1934) lived in this grand urban villa (Beethovenstrasse 10), not far from the Museum Wiesbaden. He was Jawlensky’s first patron in the city, and one reason the artist decided to move from Switzerland to Wiesbaden after separating from his companion Marianne von Werefkin. On 9 June 1921 Jawlensky signed Kirchhoff’s guest book, describing himself as an ‘artist from Ascona/Ticino’. Kirchhoff had by then already acquired five paintings by Jawlensky. By the time of the collector’s death, he would own more than 100 of his works. In May of 1928 Jawlensky moved from Nikolasstrasse 3 to Beethovenstrasse 9, directly across the street from the Kirchhoffs. From that point, if not earlier, he was an integral part of their family, who enthusiastically invited him to family events. The villa next to Jawlensky’s flat was the home of champagne manufacturer Otto Henkell, also a patron of the artist. Otto’s wife Käthe Henkell was even a member of the Jawlensky friends’ association, founded in 1929 by Hanna Bekker vom Rath to support the artist, whose health and finances had taken a turn for the worse.

Adress:

Beethovenstraße 10

65189 Wiesbaden

A traveling exhibition, the Nassau Art Association,

and “Jawlensky mania”

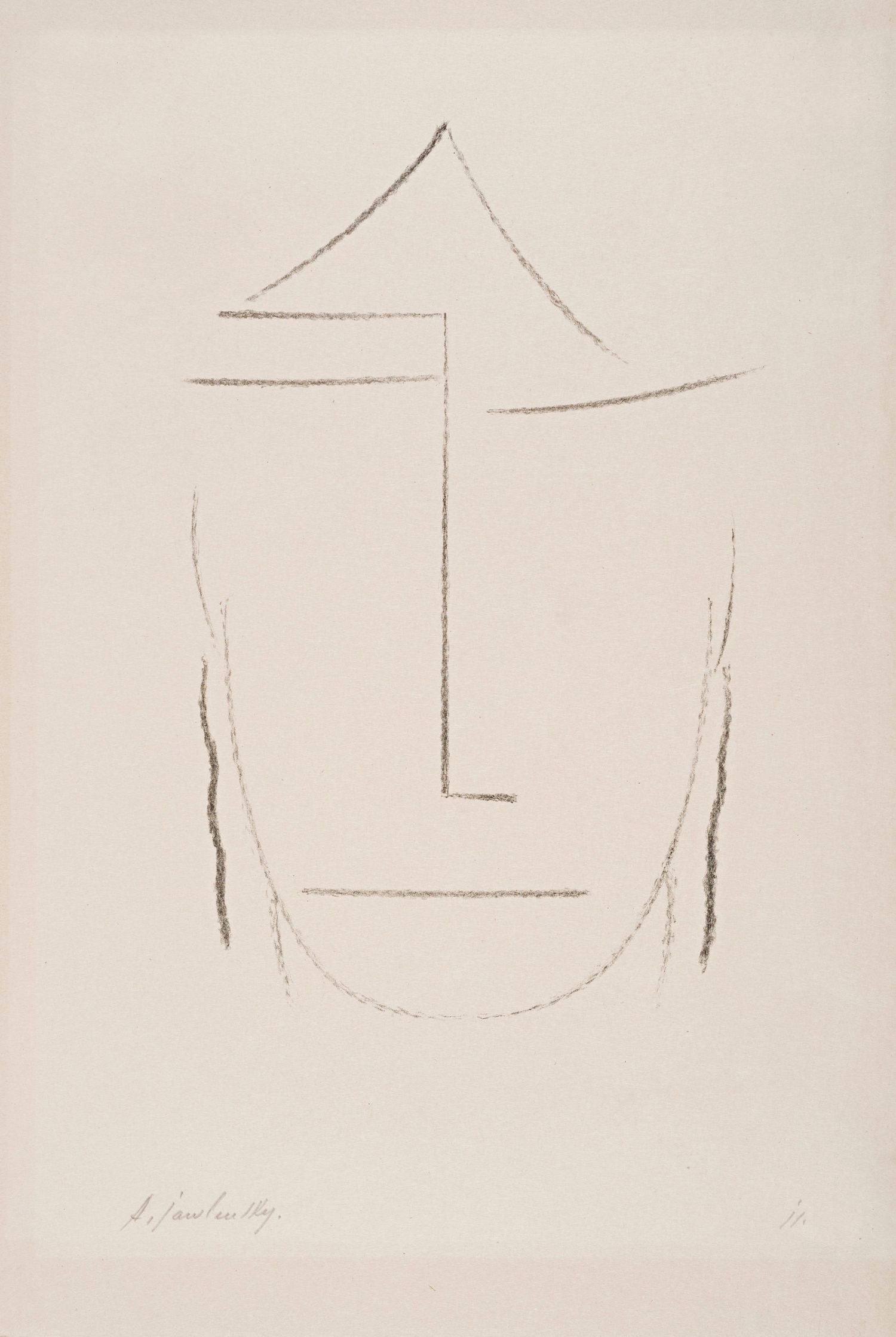

After shows in Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, Hanover, and Frankfurt, Wiesbaden 1921 is the sixth stop of Jawlensky’s traveling exhibition – and it is by far the most successful. The organizer of this Wiesbaden exhibition at the New Museum Wiesbaden was the Nassauische Kunstverein [Nassau Art Association]. Strictly speaking, it was through the Association that “Jawlensky mania” was awakened, as Galka Scheyer, the artist’s agent, later acknowledged to the city. The rest is history: Jawlensky decided to take a closer look at the city where he had had such success. He met Heinrich Kirchhoff, a patron of the arts who would become so important to him, and with the support of the Association, they found an apartment for the artist and his family in 1922, located at what is now Bahnhofstraße 25. That same year, the Association published Jawlensky’s graphic portfolio Köpfe

[Heads], whose six prints form the beginning of this year’s exhibition. Today, these works are an early testimony of the evolution towards Jawlensky’s Abstrakten Köpfen [Abstract Heads], which were to have a major impact on his art in Wiesbaden.

Adress:

Nassauischer Kunstverein

Wilhelmstraße 15

65185 Wiesbaden

The still life Bagatelles:

A sweet taste of Wiesbaden to come?

Around the turn of the twentieth century pineapple became available to the middle class in Germany, causing a stir similar to the exotic ‘super fruits’ that are touted for their health benefits today. It was also a pivotal moment for Konditorei Kunder: in 1903—four years after the long-standing confectionery shop opened its doors—Fritz and Hermine Kunder whipped up their first pineapple tartlet, a dessert that remains popular to this day. Jawlensky, who lived in Wiesbaden from 1921, could not have failed to take note of this polarizing confection—even if strawberries were his favourite fruit. The Russian avant-garde artist was clearly no stranger to pineapple, as the still life Bagatelles demonstrates. In 1904—seventeen years before he moved to Wiesbaden—Jawlensky painted a still life of a pineapple, positioned alongside two apples and a Japanese doll. In doing so, he joined a long line of European painters and sculptors who depicted the pineapple as a symbol of prosperity—a tradition dating back to the seventeenth century.

Adress:

Fritz Kunder GmbH

Wilhelmstraße 12

65185 Wiesbaden

A Piece of Russia at Home in Wiesbaden

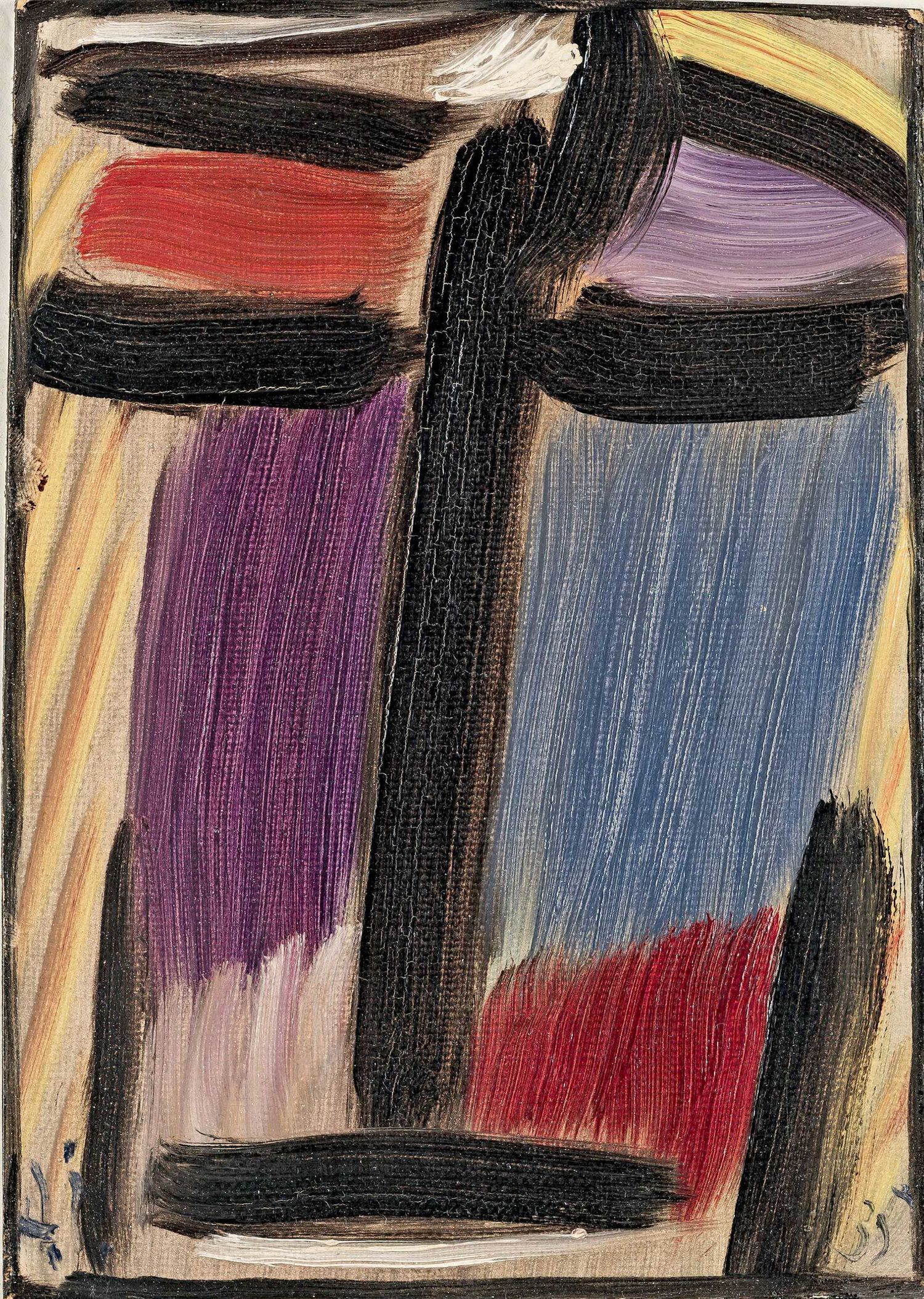

Surrounded and protected by Russian tapestries, Alexej von Jawlensky spent the last years of his life, for the most part, lying down. In the late 1920s, he was diagnosed with a severe form of arthritis deformans

that caused him to spend the last three years of his life almost completely paralyzed in bed in his apartment at 9 Beethovenstraße. The woven Russian fabrics provided warmth and comfort and most certainly reminded him of his native Russia, which he had not seen for decades. Interspersed with a myriad of ornamental patterns and richly detailed motifs, the formal language of tapestries accompanied the artist throughout his life. Their warm colors and textile structure can sometimes be recognized in the small-format Meditations, which were produced primarily in Wiesbaden (such as the piece Meditation:

My Spirit Will Live On) and which he created, almost mantra-like, beginning in 1934. Numerous works from this series will be presented as part of the exhibition The Lot!.

Adress:

Teppich Michel

Wilhelmstraße 12

65185 Wiesbaden

To see and be seen:

strolling in Warmer Damm park

Nestled between old town, the state theatre, and museum mile, Warmer Damm park has provided people with a place to relax in the middle of the city for over 160 years. Laid out in the style of an English garden, it was and continues to be an ideal location for a casual stroll—an activity that Alexej von Jawlensky, too, enjoyed. This photograph, in which the Schiller monument can be seen just left of centre, was taken in the mid-1920s. It shows Jawlensky, sauntering alongside his friends, the Kirchhoffs and the Reuters. Their joyful expressions suggest an exuberant mood. Jawlensky, standing in the middle with linked arms, appears to have fully arrived in the spa town.

Adress:

Warmer Damm Park

Paulinenstraße 15

65189 Wiesbaden

Raise your Moscow Mules, we have something to celebrate!

Alexej von Jawlensky has left his mark on the city of Wiesbaden as a center of culture for 100 years now. This is where the Russian artist spent the last decades of his life from 1921 to 1941, where he found a new home and renewed purpose as an artist, despite his debilitating illness and political disrepute. Today, Museum Wiesbaden is home to one of the largest collections of this renowned expressionist’s art worldwide and explores his work from ever-new perspectives. As a result, Wiesbaden today is both the final station and the future of Jawlensky’s art. As such, it closes the circle he himself opened in Moscow: It was there he discovered his love of art and laid the foundations of his artistic career with studies in St. Petersburg. After his travels in France, he lived in Munich and, for a time, in exile in Switzerland, before arriving in Wiesbaden in June 1921. Today, a street, a bus stop, a school, and now even a drink at BENNER’s: “Jawlensky's Moscow Mule” all bear his name.

Adress:

Benners Bistronomie

Kurhaus Wiesbaden Gastronomie GmbH & Co. KG

Kurhausplatz 1

65189 Wiesbaden

Citrus fruits and unstable still lifes

Whether Jawlensky had an affinity for confectionery and pastries is not documented, unfortunately. But for props in his still lifes he often reached for citrus fruits. He thereby demonstrated his familiarity with the work of Henri Matisse and above all Paul Cézanne, who influenced 20th century art like few others. Rolling fruits, strongly contoured draped tablecloths, and unstable perspectives are only a few of the parallels between Jawlensky’s work and that of his fellow artists. He thereby also reinvigorated the still life tradition. And because the subjects of his still lifes can also be read, quite simply, as summertime refreshments, it’s not much of a stretch to imagine Jawlensky stopping by today’s Café Blum. After all, it is located on the route between Warmer Damm park, where Jawlensky often spent his time, and the Russian Orthodox community on Neroberg, where he was buried in 1941.

Adress:

Café Blum

Wilhelmstraße 60

65183 Wiesbaden

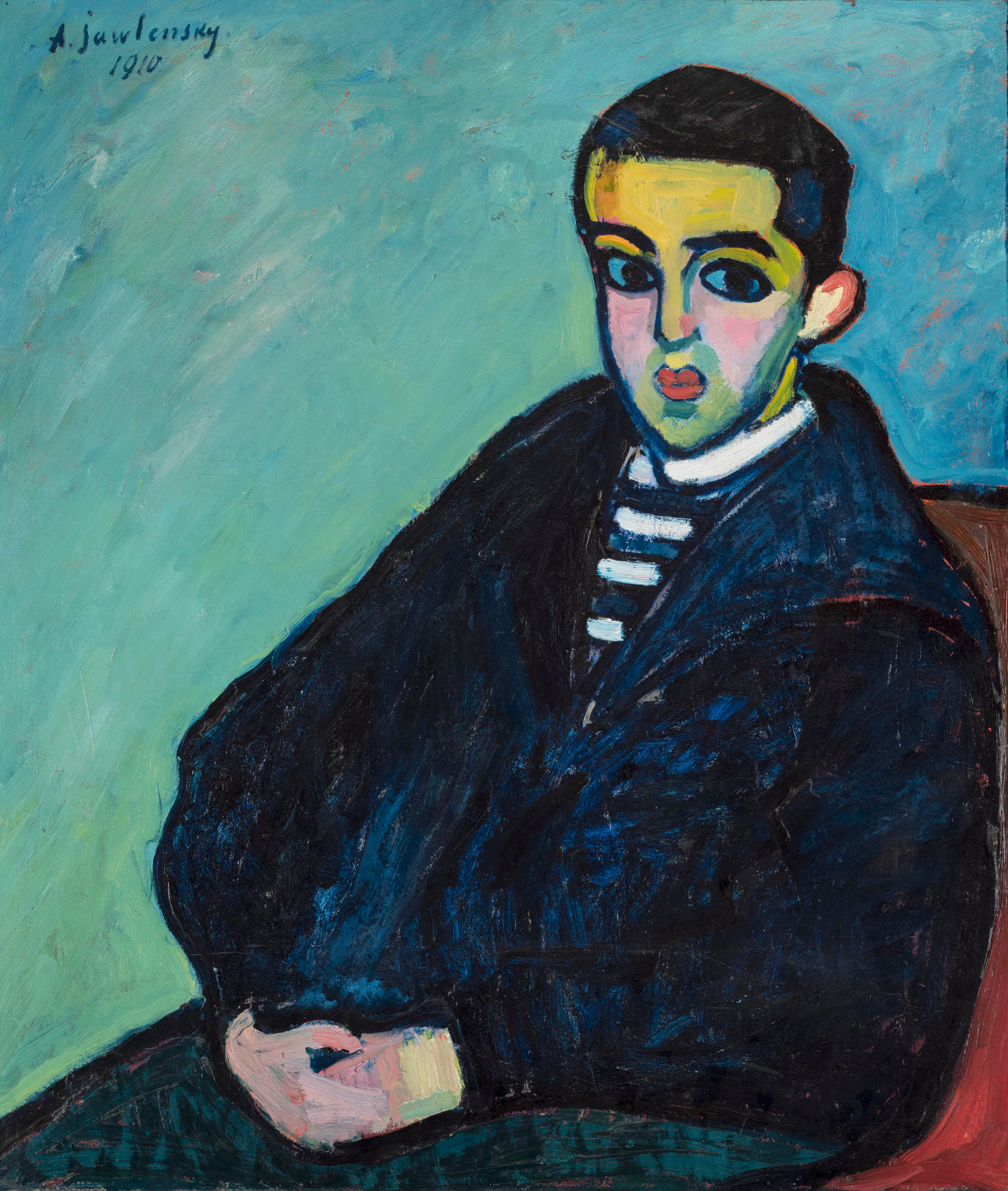

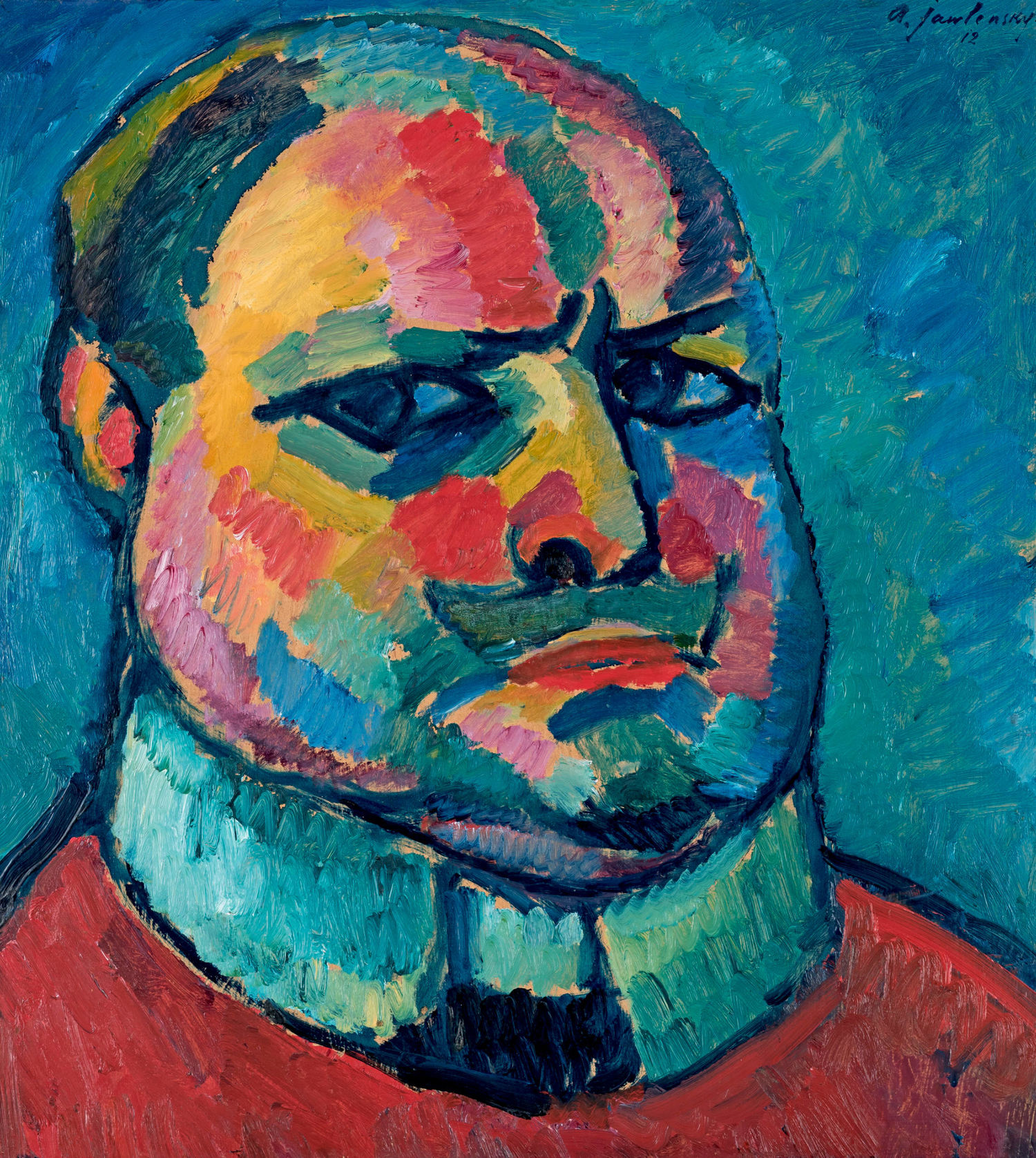

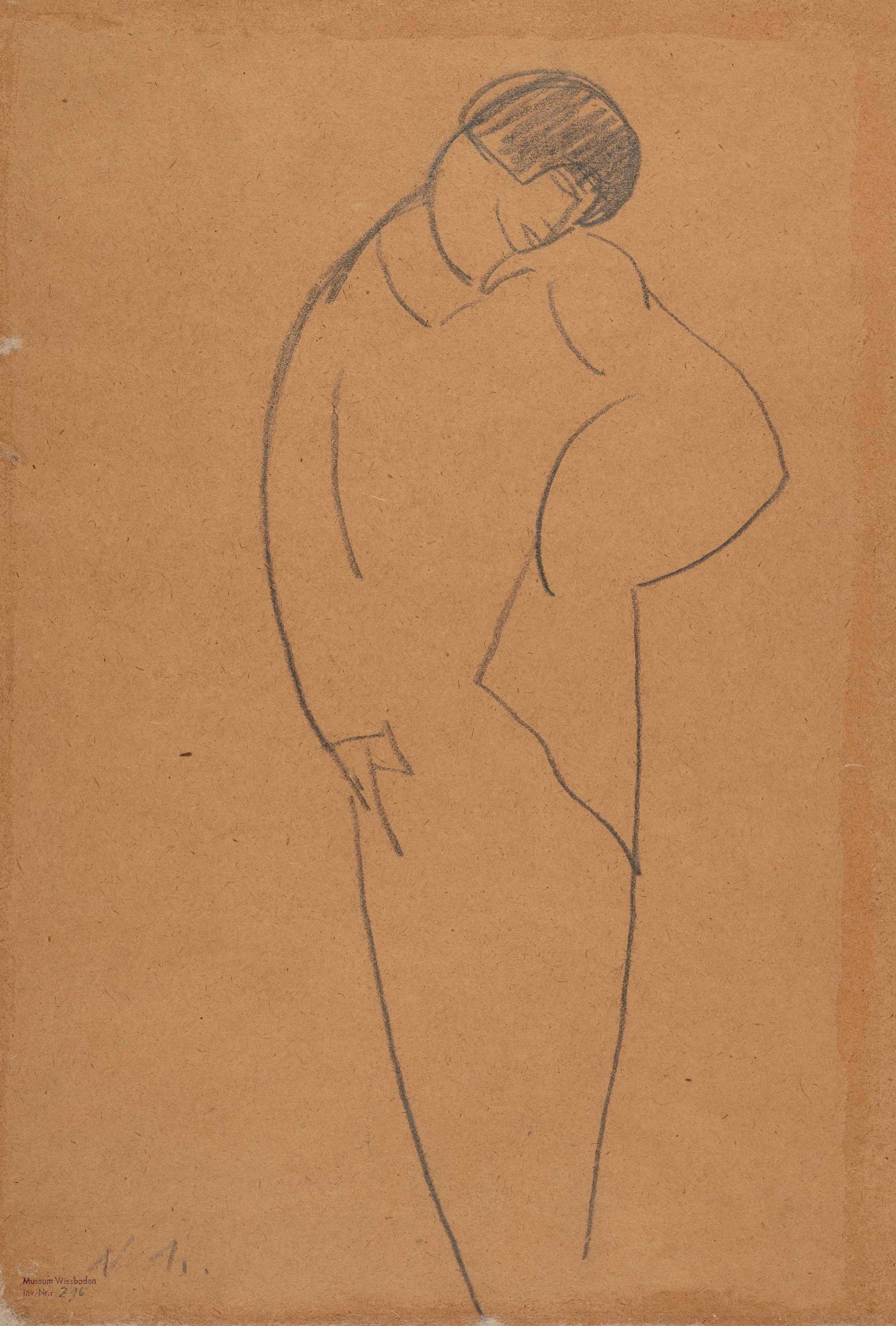

Eyes open/eyes closed

It was here on this very street, Wilhelmstraße, that the expressionist artist Alexej von Jawlensky walked from the time he moved to Wiesbaden in 1921 until his death in 1941. Living not far from here in what is now Bahnhofsstraße 25, he often met up with patron Heinrich Kirchhoff and his wife Tony for a walk in Warmer Damm or dropped by the beauty salon run by his wife Helene at the corner of Wilhelmstraße and Rheinstraße 15. These are routes he would likely have taken as he contemplated the Abstrakte Köpfe [Abstract Heads], which he created primarily here in Wiesbaden. Until 1920, Jawlensky’s portraits were still characterized by the wide-open eyes that seemed to almost glare at the viewer. Yet, with his desire to “go into greater [artistic] depth," the eyes of his heads increasingly close, through to the completely spiritual series of works the Meditations, to which he devoted himself until the end of his life.

Adress:

Gabrich Optik GmbH

Wilhelmstraße 42

65183 Wiesbaden

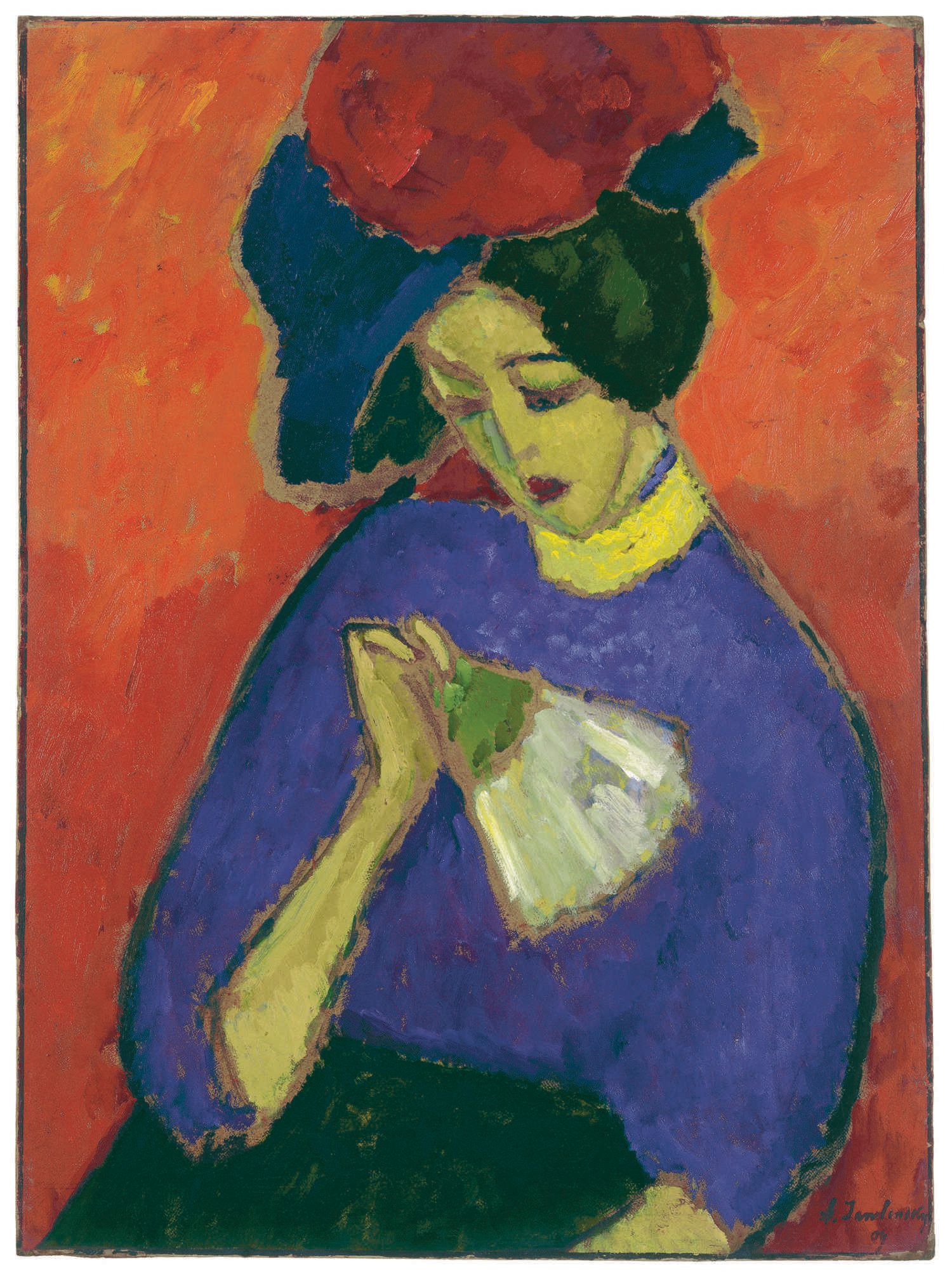

Appearance and reality in Jawlensky’s portraiture

As the saying goes, “Clothes make the person,” and, in a way, this is equally true of Jawlensky's portraits. As early as 1901/02, his future wife Helene posed in a Spanish dress for what is now the museum’s iconic portrait Helene im spanischen Kostüm [Helene in Spanish Costume] – though Helene had no connection to Spanish culture whatsoever. Here, the clothing and accessories belong exclusively to the narrative content of the representation, assigning a role to the model. So, too, with the 1906 work Bauernmädchen mit Haube [Peasant Girl with Bonnet], in which the dark red headdress and use of a predominantly earthy color palette underscore the peasant character of the depicted figure. The contrast with his Dame mit Fächer [Lady with Fan] is marked. Not only do the cheerful orange-red and blue colors virtually radiate from the image, but the appearance of the fashionable lady with opulent headdress and elegant fan emphasizes her sophistication and raise never-to-be-answered questions about the personality of the mysterious sitter.

Adress:

Corina Knoll

Wilhelmstraße 40

65183 Wiesbaden

Moving Images – Jawlensky and Film

Something we can download or even produce ourselves today with the greatest of ease, thanks to smartphones, was still an absolute sensation in Jawlensky’s day: the moving image. Though we do not know with certainty when the artist saw his first film – it is possible that he might have enjoyed a screening of the Lumière brothers during one of his stays in Paris between 1903 and 1906. Their film screenings drew large audiences to Paris as early as 1895, for example, at the 1900 Paris Exhibition. In 1926, four years after Jawlensky’s arrival in Wiesbaden, the city’s first silent movie theater Ufa im Park finally opened. It is known today as the Caligari Filmbühne, in homage to the expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Both the cinema at the Marktkirche and the award-winning expressionist film of 1919 could have been known to Jawlensky, as the cinema itself, in a prime, central location, had always been a meeting place for the cultural scene in Wiesbaden. Though we do not know whether Jawlensky was fond of film, he must have, at the very least, had an opinion on this newly emerging medium, as he cultivated friendships with people close to the theater, such as Alexander Sacharoff and Clotilde von Derp, or the media artist László Moholy-Nagy, whom he knew personally.

Adress:

Caligari FilmBühne

Marktplatz 9

65183 Wiesbaden

United at last

After numerous stations in his life—from Russia, to Munich, to Switzerland—Alexej von Jawlensky made his home here in Wiesbaden for the last 20 years of his life. The extraordinary success of his art in 1921 at the „Nassauischer Kunstverein“ and the local Russian Orthodox community had a significant influence on this decision, and he was not to regret it. Here, he found trusted friends in the cultural scene who supported him intellectually and financially even in the most difficult times of illness and political censorship. Privately, too, though, all that belongs together finally came together here on the “Dern’sche Gelände” in front of the Wiesbaden registry office with his marriage to his partner of many years and mother of his son, Helene Nesnakomoff. Both found their final resting place in the Russian Cemetery on Neroberg, though many other places throughout the city tell the story of the Russian Expressionist and his family in Wiesbaden.

Adress:

Wiesbaden Tourist-Information

Marktplatz 1

65183 Wiesbaden

A meeting with an extraordinary outcome

In the summer of 2013 a memorable conversation took place between the Museum Wiesbaden and the Wiesbaden collector Frank Brabant. The location was the ‘Maldaner’: to be specific, at Frank Brabant’s regular table. It was chosen as a kind of neutral ground, halfway between the museum and the collector’s apartment. The topic at hand was a delicate matter. Spring of 2014 would bring the 150th birthday of Alexej von Jawlensky (1864–1941), which the museum would honour with a major special exhibition. The only thing missing was a new acquisition. The museum knew that Frank Brabant owned the largest painting by Jawlensky: the life-sized portrait Helene in Spanish Costume. They posed the question: was he willing to donate it on account of the special occasion? A week later Frank Brabant called the director—he was in! He donated the painting to the museum. Since then it has been impossible to imagine the museum without the artist’s most important early work. The current exhibition, All! 100 Years of Jawlensky in Wiesbaden, dedicates an entire room to the picture. It shows the artist’s beloved, whom he married in Wiesbaden in 1922, and with whom he had a son, Andreas. Thank you, dear Frank Brabant for this generous gift!

Adress:

Café Maldaner GmbH

Marktstraße 34

65183 Wiesbaden

A site of creative exchange

When Alexej von Jawlensky arrived in Wiesbaden in 1921, the building that now houses the Kunsthaus was still used for the School of Crafts and Applied Arts. The Kunsthaus, then, was a site of creative and technical exchange, which Jawlensky must certainly have appreciated – after all, one of his closest friends and confidantes, Lisa Kümmel, was herself a graduate of a similar institution in Berlin-Charlottenburg. The re-purposing of the building much later in the 1980s would certainly have met with Jawlensky’s approval: Namely, as a place where practitioners of various artistic disciplines could bring together their creative energies, a place at times reminiscent of Marianne von Werefkin’s “pink salon, ” out of which ultimately grew the New Artists’ Association Munich. Today, the Kunsthaus on the Schulberg has been expanded to include an exhibition and event venue for the city, and continues to thrive on the pulse of the times. It would certainly still be a popular meeting place for the Russian Expressionist today.

Adress:

KunstHaus Wiesbaden

Schulberg 10

65183 Wiesbaden

A new beginning:

the Jawlensky family after 1945

After relocating to Wiesbaden in 1922, the Jawlensky family—Alexej, Helene, and Andreas—quickly became integrated into Wiesbaden city life. Alexej von Jawlensky was sponsored by well-known Wiesbaden collectors and financially supported by a friends’ association founded in his honour. Helene Jawlensky briefly ran a beauty salon in Rheinstrasse, before fully devoting herself to her husband’s care. For a time their son Andreas, an artist himself, also worked as a tea, coffee and cigar merchant. But by the war’s end in 1945, Jawlensky’s widow Helene, daughter-in-law Maria, and grandchild Lucia were left destitute in Wiesbaden, with no permanent address, clothing, or financial resources to speak of. A bomb had destroyed their flat at Beethovenstrasse 9. Like so many others in their situation, they first moved into an improvised shelter. Here at Taunusstrasse 14 the family found their first home after the war. They remained until September 1953, when they moved only a short distance away, to Taunusstrasse 28. It was there that they were at last able to once again embrace Andreas—son, husband, and father, respectively—who returned to Wiesbaden in 1955, after spending ten years in Siberia as a prisoner of war.

Adress:

THE RE/MAX COLLECTION

Taunusstraße 14

65183 Wiesbaden

Helene Jawlensky alone in Wiesbaden

Alexej von Jawlensky died on 15 March 1941 in the flat at Beethovenstrasse 9, where he lived with Helene and their son Andreas. Three months later, Andreas was ordered to the Eastern Front in Russia, as an interpreter. In February 1945 their home in Beethovenstrasse was bombed, rendering it uninhabitable. After seeking temporary emergency accommodation outside the city, Helene Jawlensky was provided with a flat, probably first as a subtenant at Taunusstrasse 14. From September 1953 she lived at Taunusstrasse 28. Her son Andreas Jawlensky would not return to Wiesbaden until October of 1955, after spending ten years as a prisoner of war. They lived here together until 1957. In 1956, when the Soviet Army invaded Hungary, brutally suppressing the popular uprising, the family decided to relocate to Locarno in Ticino. Andreas Jawlensky had the well-founded fear that the Cold War could develop into a Third World War; in this context politically neutral Switzerland seemed like a safe refuge and a suitable place to call home.

Adress:

Goldrausch Friseure

Jawlenskystraße 2

65183 Wiesbaden

What does ‘home’ mean?

The domiciles and lives of the Jawlensky family

Torzhok – Moscow – St. Petersburg – Munich – Saint Prex – Zurich – Ascona – Wiesbaden. What was life like for the artist and his family, who relocated countless times? Some of the moves were voluntary, while others were due to political exigencies—from Russia to Germany, to Switzerland, and back again to Germany. One thing remained constant, however: at home they were always surrounded by Alexej von Jawlensky’s art, in part because they lacked proper storage space. As both a mainspring and a source of income, art was omnipresent in the Jawlensky household, where it was arranged in a constant dialogue with sculptures of the Virgin, ornamental textiles, and work by artist friends. It was thus precisely the Russian icons and artworks by Jawlensky and his colleagues that defined the family’s home, regardless of its location. This is also true of the small vases and other vessels presented in the exhibition, which the artist painted time and again in his still lifes. Today the vases and small bottles appear rather mundane—but this makes Jawlensky’s depictions of these objects, imbued with the radiance and significance that he attributed to them, shine all the brighter.

Adress:

Casa Nova Einrichtungen GmbH

Taunusstraße 37

65183 Wiesbaden

Neroberg:

the grave of Alexej and Helene von Jawlensky

Alexej von Jawlensky died in his Wiesbaden flat at Beethovenstrass 9 on 15 March 1941. He was buried three days later in the Russian Orthodox cemetery on the hilltop known as Neroberg: ‘a gorgeous corner of the world, ’ as Lisa Kümmel wrote to a friend of Jawlensky’s after the funeral. His lifelong companion Adolf Erbslöh gave the eulogy. Jawlensky had visited Erbslöh at his home in Munich in 1937; it was his last major trip. Together they went to the exhibition ‘Degenerate Art’, which the Nazis had designed as a public attack on the avant-garde. Jawlensky was represented in the exhibition by two paintings and several works on paper; it was the low point of his career. A thoroughly apolitical painter, he felt defenceless and deeply misunderstood. This ‘dark’ turn in cultural policy that oppressed Jawlensky enormously during the last years of his life appeared to lift on the day of his death: like the day of his funeral, it brought ‘wonderful spring weather’. His wife Helene died on 17 March 1965 in Locarno and, at her arrangement, was buried beside Jawlensky.

Adress:

Russisch-Orthodoxe Kirche der hl. Elisabeth und ihr Friedhof

Christian-Spielmann-Weg 2

65193 Wiesbaden

Lisa Kümmel helps Jawlensky

Lisa Kümmel (1887–1944) was one of Alexej von Jawlensky’s four most important female supporters, along with Hanna Bekker vom Rath, Mela Escherich and Tony Kirchhoff. She grew up at Rüdesheimerstrasse 22. From 1905 her father ran a very successful carpenter’s and glazier’s workshop. In fact, it made enough money to pay for Kümmel’s artistic education in Berlin. After a brief stint teaching at the renowned Wiener Werkstätte in 1922/23, she moved back to her parents’ house in Wiesbaden’s Rheingauviertel. In 1927 she met the painter Jawlensky at a masked ball. In a letter to Ada and Emil Nolde, dated 18 October 1938, she summed up her relationship with Jawlensky, who was now almost completely crippled: ‘I’m his friend in the best sense of the word. We’ve known each other for twelve years. I take care of all his written business exchanges, and now assist with his personal life as well. I look after his paintings, put everything in order, glue, wax, varnish, etc.’ They trusted one another so completely that between 1935 and 1937, shortly before Jawlensky died, he dictated his oft-quoted memoirs to her.

Adress:

BBK-Berufsverband Bildender Künstlerinnen und Künstler Wiesbaden e.V.

Marcobrunnerstraße 3

65197 Wiesbaden

Jawlensky’s early days in Wiesbaden

The exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden in January/February 1921 proved to be the most successful stop on Jawlensky’s major retrospective tour of Germany. In total, 20 paintings were sold. Wiesbaden thus piqued the artist’s curiosity, and he visited the city on 1 June 1921. After spending seven years in Switzerland, he longed to return to Germany. The local art scene welcomed him with open arms and before long, he started to think that Wiesbaden might be the place to be. A frequent traveller, Jawlensky was in Wiesbaden only sporadically during that first year. He didn’t have a permanent address until the spring of 1922, when his family joined him from Ticino. Until that point, one of the return addresses on his letters was ‘care of the Teihert Family’ at Rathausstrasse 10, Biebrich, Wiesbaden. He likely became acquainted with the Teiherts through the Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden, which put out an advertisement for a 4 to 5 room apartment on his behalf in May 1922. Eventually, Jawlensky found a flat at Nikolasstrasse 3 (today Bahnhofstrasse 25).

Adress:

Nachbarschafthaus Wiesbaden e.V.

Rathausstraße 10

65203 Wiesbaden

Flowers by Jawlensky

While the term “bouquet” is used in viticulture to describe the composition of a wine’s various scents in the glass, the actual meaning of the French term bouquet, as in a bouquet of flowers, played a very special role for the expressionist artist Alexej von Jawlensky. He was to paint flowers over and over again until the end of his life – as an exercise in dexterity and for their appeal to potential customers. The latest addition to the Jawlensky collection at Museum Wiesbaden is also a still life with flowers. Produced in 1937, it must have been one of Jawlensky’s last artistic expressions, for as his illness advanced in his final years, he was hardly able to get out of bed. In radiant hues, this new still life foregrounds the striking color of the flowers against a dark background. One might say, the flower bouquet can be seen as a metaphor for the career of the renowned expressionist artist, who despite political hardship and debilitating illness never lost his creative spirit.

Adress:

Wein Lounge — Wiesbaden

Freudenbergstraße 200

65201 Wiesbaden

In memory of Jawlensky’s confidante Lisa Kümmel

Lisa Kümmel (1897–1944), close friend and confidante of Alexej von Jawlensky (1864–1941), was buried under the rubble during a bombing raid in Wiesbaden-Erbenheim in 1944 and died a short time later from her injuries in Josephs Hospital. Kümmel lived in Wiesbaden’s Rheingauviertel, from where she made the journey to Jawlensky’s house on Beethovenstraße almost every day at 2 p.m. to help the increasingly feeble artist organize and catalogue his paintings. The two had known each other since 1927 – presumably, they met at a ball one evening at a carnival celebration in the Wiesbaden Kurhaus. Their close, almost father-daughter-like relationship is confirmed by the fact that between 1935 and 1937, shortly before his complete paralysis, Jawlensky continued to dictate to her his memoirs, which now play so valuable a role for research.

The Domäne Mechtildshausen operates the “Café Mechtild” in Museum Wiesbaden, where the extensive anniversary exhibition 100 Years of Jawlensky in Wiesbaden is taking place. To mark this festive occasion, the café is featuring traditional Russian pluck cake “Alexej” in finest organic quality, both in the museum and in the on-site pastry shop.

Adress:

Domäne Mechtildshausen

Mechtildshausen 1

65205 Wiesbaden

Alexej von Jawlensky, Saviour's Face: Expectation, 1917. Museum Wiesbaden, Photo: Museum Wiesbaden ⁄ Bernd Fickert

Learn more about the exhibition

on our website!