Exactly 100 years after the privatier and art collector Heinrich Kirchhoff displayed his substantial art collection of avant-garde works for the first time in the Museum Wiesbaden, this collection will be brought together again in the same location. Kirchhoff (1874–1934) moved to the spa town of Wiesbaden at the end of 1908 with the desire to dedicate himself to his passions of art and nature. Within a year, he had gathered an art collection that united exquisite works by avant-garde artists such as Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, and Franz Marc. At Kirchhoff’s invitation, Alexei von Jawlensky came to Wiesbaden and took up residence here until the end of his life. Kirchhoff’s villa at Beethovenstraße 10, with its remarkable garden that the collector himself had created, offered a paradisiacal idyll. Botanists and art enthusiasts alike were drawn by its magic. From early on, Kirchhoff intended for his collections to be open to everyone and also for the city, with these collections serving as an example, to become a center for artistic Modernism.

“Just returned from the garden, I must admit that it possesses an unusual allure and enchantment; it is as if the garden did not actually exist at all. It is so unreal, as unreal as art, which does not actually exist either. In fact, there is no Heinrich Kirchhoff, for he is as unreal as his garden and his pictures.” (Kurt Schwitters, 1927)

Kirchhoff’s garden paradise in Wiesbaden, which was also visited by “Garden Art” experts, was extraordinarily beautiful. August Siebert, the director of the Palmengarten in Frankfurt am Main, visited Kirchhoff multiple times and was full of respect and recognition for him. Famous visitors from all over Germany were already signing their names in the family’s guestbook. During the period of crisis after World War I, this special place offered an idyll for artists that served as a source of inspiration for them. This is clearly documented in numerous works in which exotic plants in gardens serve as common motives. Similarly, small drawings were left behind by visiting artists, such as Conrad Felixmüller and Paul Klee.

Kirchhoff's Garden in Wiesbaden, Beethovenstraße 10, around 1920.

Kirchhoff’s art collection began primarily with German Impressionist paintings. With a remarkable intuition for quality, the Wiesbaden collector purchased important works painted by the triumvirate that was highly praised and ably-promoted by Paul Cassirer: Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt. At the beginning of the 20th century, the new type of en plein air painting from France, which was devoted to painting in nature, was a part of the avant-garde, which the emperor did not appreciate. However, these artists became extremely popular among the rising bourgeois and enjoyed great demand for their work. In 1918, Kirchhoff, too, commissioned Liebermann, the most popular portraitist of the time, to paint his portrait. In the circle of great masters, numerous other artists, whose works were influenced by Impressionism, received the collector's attention. These artists included Wilhelm Trübner, Julius Hess, Oskar Moll, and the young Max Beckmann.

Max Liebermann, who was a frequent visitor of Wiesbaden, developed a lifelong friendship with Kirchhoff. It is probable that Kirchhoff's interest in the Berlin Secessionists can be traced back to this connection. The Berlin Secession emerged around the turn of the century as a counter-movement to the established art business. This movement aimed to give young artists backing against the conservative state-run Association of Berlin Artists. Kirchhoff closely followed the movements of the Berlin art scene and tried to emphasize corresponding artistic groups through his purchases.

The Expressionists were at the heart of Kirchhoff’s collection. During World War I, Kirchhoff had already begun to collect color intensive and technically expressive paintings. He searched for contemporaneous exemplary works that specifically captured the multi-faceted nature of Expressionism. Kirchhoff endeavored to invite the artists of these works to Wiesbaden and, furthermore, to understand their art through personal conversation. Each artist stood for his own artistic position, thereby bringing a diversity of intellectual and stylistic trends that reflected a comprehensive overview of German Expressionism.

The November Revolution (1918–1919), which eventually replaced the monarchy with the first German democracy, contributed to these changes in many respects. From the destruction, artistic ideas for a new way of life emerged through geometrically abstract constructions. In 1921 and 1922, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Lyonel Feininger joined the Bauhaus as teachers. László Moholy-Nagy joined as well a year later. Around this time, Kirchhoff began to sell his Impressionist works and increasingly turned to these representatives of the Bauhaus. Considering that he had been collecting art for only ten years at that point, Kirchhoff’s path from Impressionism to Abstraction was radical and uncompromising.

Many artists fell into life and creative crises after experiencing the horrors of World War I. Above all, young talents, whose studies had been abruptly interrupted by the war, now lived on the poverty line. During this time, Heinrich Kirchhoff was particularly committed to painters still at the beginning of their careers. Among them were Josef Eberz, Conrad Felixmüller, and Walter Jacob. As a “patron of Modernism,” Kirchhoff provided them with intense support, accommodation, and studio spaces in Wiesbaden. Thus, numerous works, oftentimes depicting the collector’s surroundings, were made on site.

The most notable artist whom Kirchhoff supported in Wiesbaden was Alexei von Jawlensky. After his exile in Switzerland, Jawlensky moved back to Germany. His travelling exhibition (1920–1921) was in no city as successful as in Wiesbaden. Henry Kirchhoff, who immediately acquired five paintings by the artist and invited him to his 'garden of the avant-garde', played a key role in Jawlensky’s success. Jawlensky settled down shortly afterwards in Wiesbaden. The increasing abstraction in his works and his serial treatment of a recurring theme – namely variations on a garden – aroused Kirchhoff’s fascination and led to the acquisition of more than 100 works by Jawlensky, including at least 50 oil paintings.

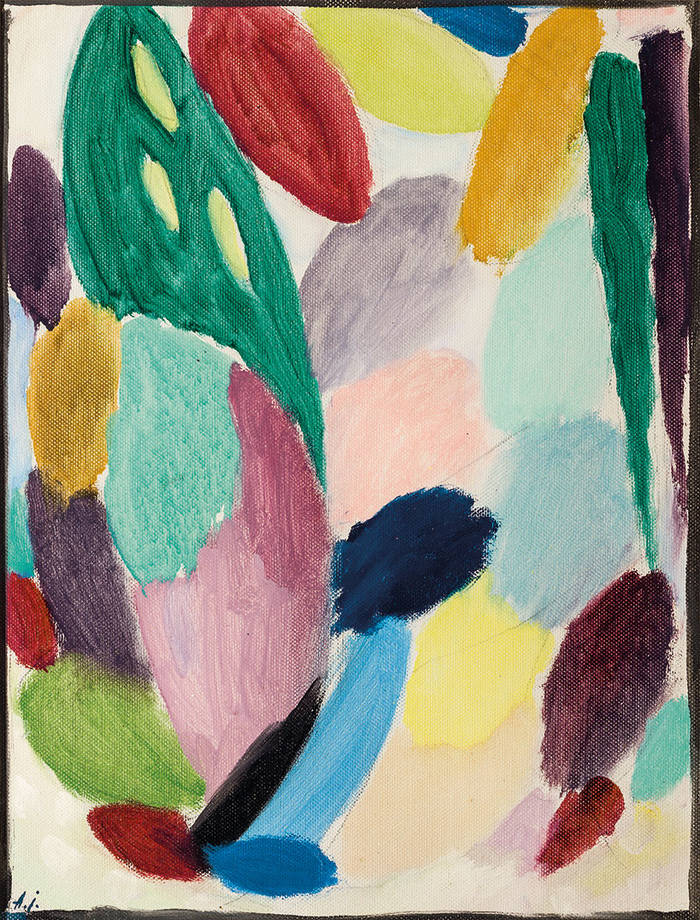

Alexei von Jawlensky, Variation – Fresh and Sounding, around 1918, Merzbacher Kunststiftung.

With his garden and his paintings, Heinrich Kirchhoff also attracted other art collectors, historians, and dealers. The visits of the artist Hanna Bekker vom Rath turned out to be of paramount importance to the Museum Wiesbaden. She began to collect art herself around 1920, probably influenced by Kirchhoff´s magnetism for artists and strong personality. Her private art collection, with works by artists such as Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Adolf Hölzel, Alexei von Jawlensky, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, came to the Museum Wiesbaden in 1987, where it currently forms the high-quality foundation of the "Classical Modernism" collection. The artists in Kirchhoff’s collection had discovered and come to appreciate these paintings.

Heinrich Kirchhoff und Alfred Flechtheim at the back entrance of Museum Wiesbaden, 1918.

The end of the Kirchhoff collection came abruptly. In 1934, it was removed from public space and returned to the collector's family because of political upheavals. Shortly thereafter, Heinrich Kirchhoff died. Political events and family misfortune led to the collection’s dissolution by the family; thus, an irreplaceable piece of collected art history was lost. The unique garden became a victim of World War II. Today, the works from the former Kirchhoff collection are exhibited in the most renowned museums around the world, which speaks for their exceptional quality and significance.

Der Garten der Avantgarde

Heinrich Kirchhoff: Ein Sammler von Jawlensky, Klee, Nolde…

Roman Zieglgänsberger and Sibylle Discher (Editors)

Imhof Verlag, 2017

ISBN 978-3-7319-0584-4

Euro 35,-

Contributed by Annette Baumann, Astrid Becker, Herbert Billensteiner, Sibylle Discher, Peter Forster, Franz Josef Hamm, Gerhard Leistner, Miriam Olivia Merz, Jutta Penndorf, Christiane Remm, Roman Zieglgänsberger

Only available in German language.