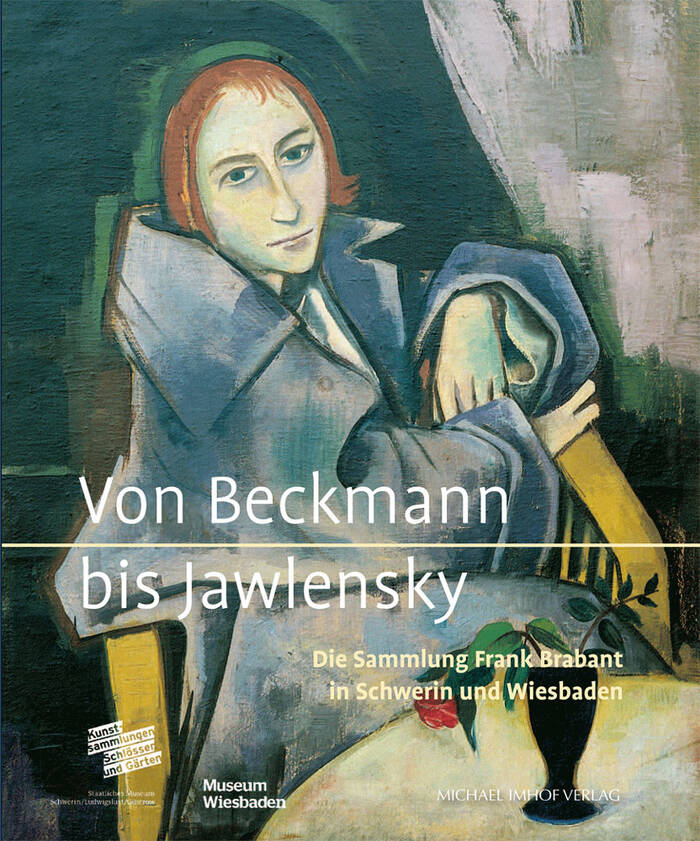

Collection Frank Brabant, Photo: Museum Wiesbaden / Bernd Fickert

On the occasion of his 80th birthday, the Wiesbaden collector and patron of the arts Frank Brabant made a significant endowment: His extensive art collection, consisting chiefly of Classical Modernist works of Expressionist and New Objectivist art and encompassing some 600 works, will one day be bequeathed to the Staatliche Museum in Schwerin, the city of his birth in 1938, and Museum Wiesbaden in the city where he has resided for almost 60 years.

The exhibition From Beckmann to Jawlensky includes not only major works by renowned artists but presents a broad spectrum of art from the first half of the 20th century and clearly demonstrates the seamless fit of Brabant's collection into the collection of Classical Modernism at Musuem Wiesbaden.

The exhibition includes works from Heinrich Campendonk, Otto Dix, Lyonel Feininger, Conrad Felixmüller, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Hanna Höch, Karl Hofer, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexander Kanoldt, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Käthe Kollwitz, August und Helmuth Macke, Jeanne Mammen, Franz Marc, Ludwig Meidner, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Otto Ritschl.

Born in Schwerin in 1938, Frank Brabant has lived in Wiesbaden since 1958. It is here that the one-time discotheque owner – he was proprietor of the infamous Pussycat club well into the 1990s, where he welcomed such illustrious guests as Udo Jürgens and Donna Summer – became a passionate collector of art. Brabant’s main focus is on expressionist and modernist art of the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century and the Weimar period between the two World Wars.

His first acquisition, a woodcut by Max Pechstein, was purchased in 1964 at Hanna Bekker vom Rath’s “Frankfurter Kunstkabinett.” The collector, patron and art dealer Hanna Bekker (1893–1983) shaped Brabant’s taste through her selection of works in this gallery, which was centered around the work of the artists’ associations “Die Brücke” and “Der Blaue Reiter.” Brabant bought works from Bekker’s gallery again and again, sometimes in installments. For her part, Hanna Bekker was shaped in her taste by Wiesbaden-based patron and collector Heinrich Kirchhoff (1874–1934), whom she visited twice (1918 and 1927) in his villa and whose enthusiasm was most certainly contagious.

In the tradition of these remarkable and generous collector-patrons, Frank Brabant bestowed a gift to Museum Wiesbaden in 2014 – the largest painting Jawlensky ever produced, Helene im spanischen Kostüm (Helen in Spanish Dress). More than that, in 2017, he decided to transform his collection of more than 600 works of art into a foundation that is to benefit the two museums of the places that shaped him most – Schwerin and Wiesbaden.

Frank Brabant in the exhibition, Photo: Museum Wiesbaden / Bernd Fickert

It all started with a woodcut by Max Pechstein, which Frank Brabant bought with the money he had saved for his first VW Beetle. Later came works by Alexej von Jawlensky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, August Macke, Georg Tappert, Emil Nolde, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann and many others. Brabant single-mindedly acquired works from the early avant-garde, with a focus on the context of the Junge Rheinland [Young Rhineland], the Berlin Secession, the November Group, the Brücke, the Blaue Reiter, the Sturm or Magischer Realismus movements. One key aspect of the collection are works by what became known as the ‘lost generation’. These were the artists who had to interrupt their careers or else continue them in exile as a result of the Second World War, expulsion, expatriation, or the Nazi dictatorship.

In the exhibtion there will be works of art from:

Heinrich Campendonk, Otto Dix, Lyonel Feininger, Conrad Felixmüller, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Hanna Höch, Karl Hofer, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexander Kanoldt, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Käthe Kollwitz, August und Helmuth Macke, Jeanne Mammen, Franz Marc, Ludwig Meidner, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Otto Ritschl…

Frank Brabant's passion for collecting was awakened by works from the early avant-garde artists’ associations “Die Brücke” and “Der Blaue Reiter.” Max Pechstein's woodcut. Soon thereafter, he acquired works by Fritz Bleyl, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Mueller, Erich Heckel, Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, all of whom belonged to “Die Brücke,” an artists’ group founded in Dresden in 1905. But Brabant’s interest extended, as well, to painters from the circle around “Der Blauer Reiter,” founded in Munich in 1911. Aside from Heinrich Campendonk, Adolf Erbslöh, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke and Franz Marc, he was particularly drawn to the work of Alexej von Jawlensky, from whom he has at least one representative piece from each phase of his artistic development. Perhaps Brabant’s special relationship to the work of this Russian artist lies in the shared experience of having made Wiesbaden their adoptive home. Jawlensky settled in Wiesbaden in 1921 and remained here until his death in 1941. He was an influential presence in the city both before and after the Second World War and continues to have a formative effect long after – and this in the city where Frank Brabant, too, would come to settle.

The works of César Klein, Siegfried Bernd and Curt Erhardt demonstrate Brabant’s interest, from the very start of his collecting activities, not only in major figures but in those artists whose work had fallen into oblivion due to the caesura of National Socialism. Many of these painters, such as Jeanne Mammen or Hanna Höch, who Brabant collected early on, have only been recently rediscovered.

Both Expressionism and New Objectivity are dominated by genres introduced centuries ago: figure painting, landscape and still life. In Frank Brabant’s home, where there is always at least one large bouquet of flowers in the living room, hang innumerable exemplars of a subgenre of still life painting: the flower painting. The subjects of these many floral representations seem to mutually complement the collection's two contrasting styles. The sweeping brushstrokes of the “expressive,” passionately executed flower paintings (by Maria Caspar-Filser or Siegfried Donndorf) convey, above all, the vitality of nature, while the clearly depicted arrangements of the “modern” flower paintings (by Carlo Mense or Grethe Jürgens), like frozen moments with sharply drawn lines and richness of detail, underscore its variety. Finally, holding a special place in the collection for its synthesis of temperament and precision, there is Paul Kuhfuss' painting Blumen im Bauerkrug (Flowers in a Pitcher). The position of absolute highlight, however, must be conceded to Max Beckmann’s Stillleben mit grüner Kerze (Still Life with Green Candle). Produced in 1941 while Beckmann was in exile in Amsterdam during the Second World War, it serves as a memento mori in the midst of this crisis of humanity, reminding us of the transience of all life symbolized by the withered red flowers ready to drop off the stem at any moment and the candle on the verge of extinguishing into smoke.

The Weimar years from 1919 to 1933 were marked by the dichotomy between rich and poor, by conspicuous hardship and excessive revelry. New Objectivity emerged around 1915 as a counterposition to abstract art and became the ideal medium for artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz, Käthe Kollwitz and Rudolf Schlichter to unequivocally express their critical attitude towards war, misery and social distortions. With forceful works, showing dismembered bodies, soldiers (already dead) aiming in every direction with their guns, or “happy” survivors as fully incapacitated war cripples, these artists pointed the finger at those who were to answer, rubbing proverbial salt in the wound. The pointed sharpness of their subjects and great precision of their depictions makes the desired effect of these works sustainably palpable.

While Ludwig Meidner, already at the beginning of the First World War in 1915, depicts the streets of Berlin intoxicated and “out of joint,” if you will, Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler examines the emaciated human being in solitary existence. The sheer ruthlessness of the stronger is thematized by Karl Hubbuch’s depiction of murderous sex crime and by Wiesbaden’s own, largely unrecognized painter Alois Erbach, who – by attentively observing his surroundings through the window of his narrow artist’s retreat – finds enlightenment as he seems to interrogate himself in a detective’s trench coat.

Ludwig Meidner, drunk street, 1915, Collection Frank Brabant

Many of the artists in Frank Brabant's collection – inspired by the spirited paintings of Vincent van Gogh – were firmly in the wake of Expressionism at the beginning of their careers. One such artist was Georg Tappert, who around 1910 might still have been easily exhibited alongside Alexej von Jawlensky (room 2), but who, around 1919, as co-founder of the November Group in Berlin, had made the turn towards New Objectivity (room 6/8). Karl Hofer (room 6), who still belonged to the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (Munich New Artists’ Association) in 1909, underwent a similar development before, from the 1920s onwards, taking a middle path between the impulsive application of color and the representation of melancholic figures. All of Hofer’s works possess a very lifelike presence, as best illustrated in his greatest work Mädchen mit blauer Vase (Girl with Blue Vase). Conrad Felixmüller, who in his early days was strongly influenced by the work of “Die Brücke,” founded in Dresden, his place of birth, in 1905, can also be seen as a mediating figure between Expressionsim and New Objectivity, specifically, his works created after the First World War.

This emerging trend was taken up by the exhibition New Objectivity - German Painting since Expressionism, initiated in 1925 by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, director of the Kunsthalle Mannheim, which classically arranged the work of artists (such as Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, August Wilhelm Dressler, Ulrich Neujahr or Alice Sommer - Room 7) by genre: portrait, still life, landscape or cityscape.

Von Beckmann bis Jawlenksy.

Die Sammlung Frank Brabant in Schwerin und Wiesbaden

Dirk Blübaum, Gerhard Graulich, Alexander Klar und Roman Zieglgänsberger (Editors)

Contributed by Gerhard Graulich, Roman Zieglgänsberger, Katharina Uhl, Deborah Bürgel, Sibylle Discher, Moritz Jäger, Vera Klewitz, Kornelia Röder and Rebecca Krämer

304 Pages

Michael Imhof Verlag 2017

ISBN 978-3-7319-0557-8

29,90,- Euro

Only available in German language.