Joseph Beuys, Honigpumpe am Arbeitsplatz. Photo: Alwis Wilmsen

If he had lived that long, Joseph Beuys would have turned 100 on 12 May. He succumbed to an inflammation of the lungs in 1986. Andy Warhol, Beuys’s junior by seven years, passed a year after him. The two met in 1979. That year, in the fall, Beuys was given his first major retrospective, at the Guggenheim in New York. But he had already made Warhol’s acquaintance in Düsseldorf earlier that year, in May. At the time, the German press beefed up the encounter as some kind of summit meeting between two masterminds of the art world. But the ‘summit’ actually entailed very little talk: Beuys, as is documented in surviving footage, merely stated to Warhol that he had long wanted to meet him and that their paths had almost already once crossed in Darmstadt. Rather than engaging in further conversation, Warhol, as was his wont, asked if he might take a quick snapshot of Beuys — and with no further ado whipped out his pocket camera, ever at the ready, to take the shot.

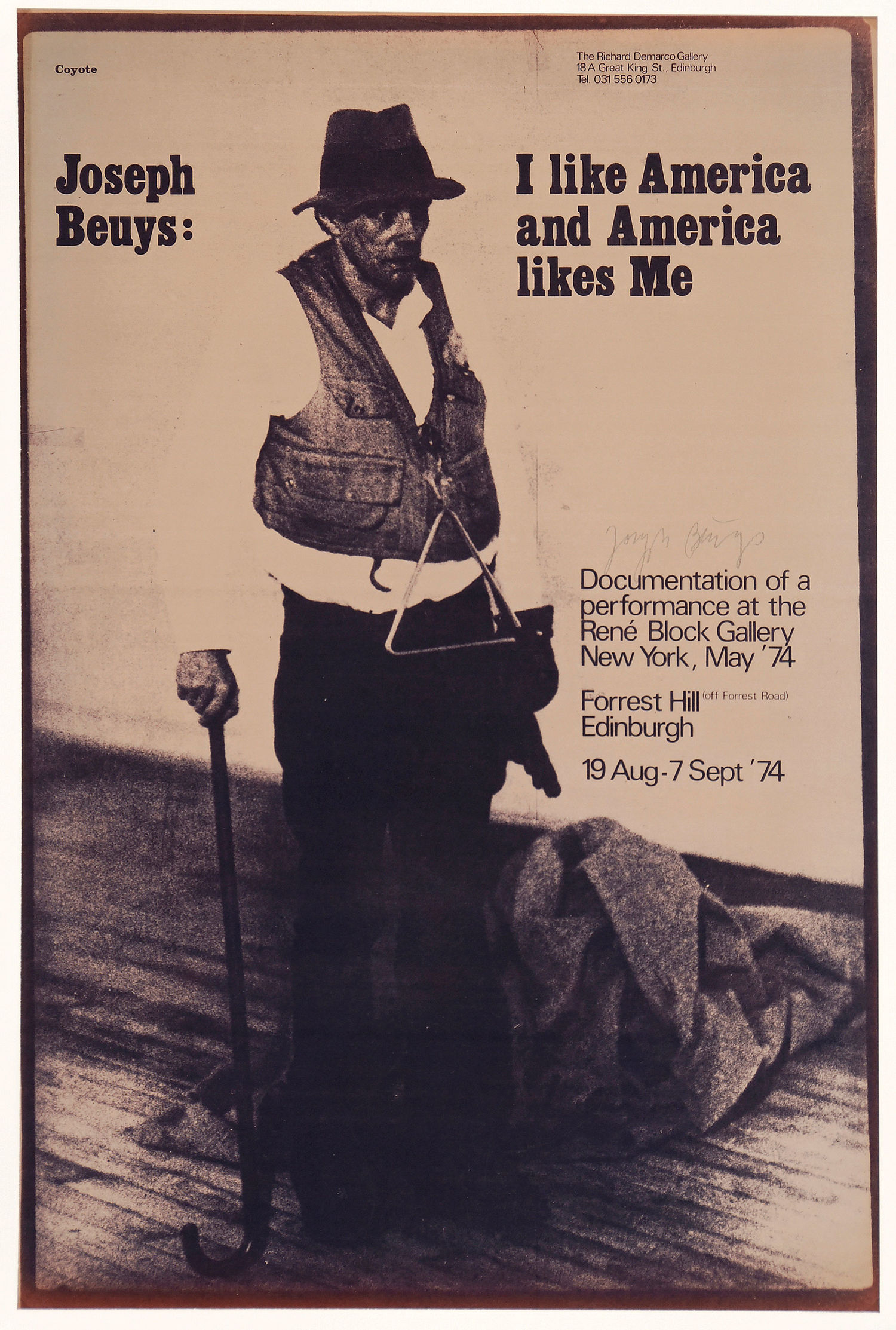

Beuys himself had already been in the US five years earlier. At that time, however, he had ‘refused’ any contact, not with Warhol necessarily, but with all New Yorkers per se. Although his action from that time bore the title I like America and America likes Me (1974), the only ‘American’ whose company he in fact sought was a coyote – displaced inhabitant of a different kind of America, far beyond Manhattan’s glittering skyline and bustle. The coyote represented the exact counterpoint to the glossy, garish images of the advertising industry, Andy Warhol’s Factory output, and the ‘American way of life’. And yet, the two artists would have probably had more to say to each other than their starkly contrasting milieus and their first Düsseldorf encounter would suggest. Months later their paths crossed again, this time on US turf, in New York, which is when Warhol took the now-legendary photograph for his series on Beuys. And then there is the oft-cited quote by Warhol that seemingly testifies to his interest in, if not understanding for, the sociopolitical thrust of Beuys’s art: ‘I like the politics of Beuys. He should come to the US and be politically active there. That would be great… He should be president.’

But leaving this statement aside, it is worth considering these two figures together, even though they at first seem such polar opposites. For despite their apparent differences, both made a myth out of their life and imbued everyday encounters with an aura. Put simply: both artists utterly blurred the line between their personal life and their art. Whenever Beuys made a public appearance, delivered a lecture, did anything, he did so as an artist — but at the same time as ‘Joseph Beuys’, who could no longer be separated from a life as performance. The same goes for Andy Warhol. And while Beuys merged with his own myth and loaded everything with deeper meaning, Warhol emphasized the fleetingness and superficiality of the world in which he lived — and wanted to live — and which he celebrated with his whole being. Put crudely, each outlined the historical moment of their respective society: the Old World, tradition (including an art-historical tradition) going back millennia vs. the New World and boundless possibilities into the future. Or, to phrase it in more critical terms: alienation and the atrophy of the senses of modern man on the one hand, vs. rising turbo-capitalism and a dissolution of individual identity in a sea of meaningless — the now proverbial ‘five minutes of fame’ enjoyed by everyone.

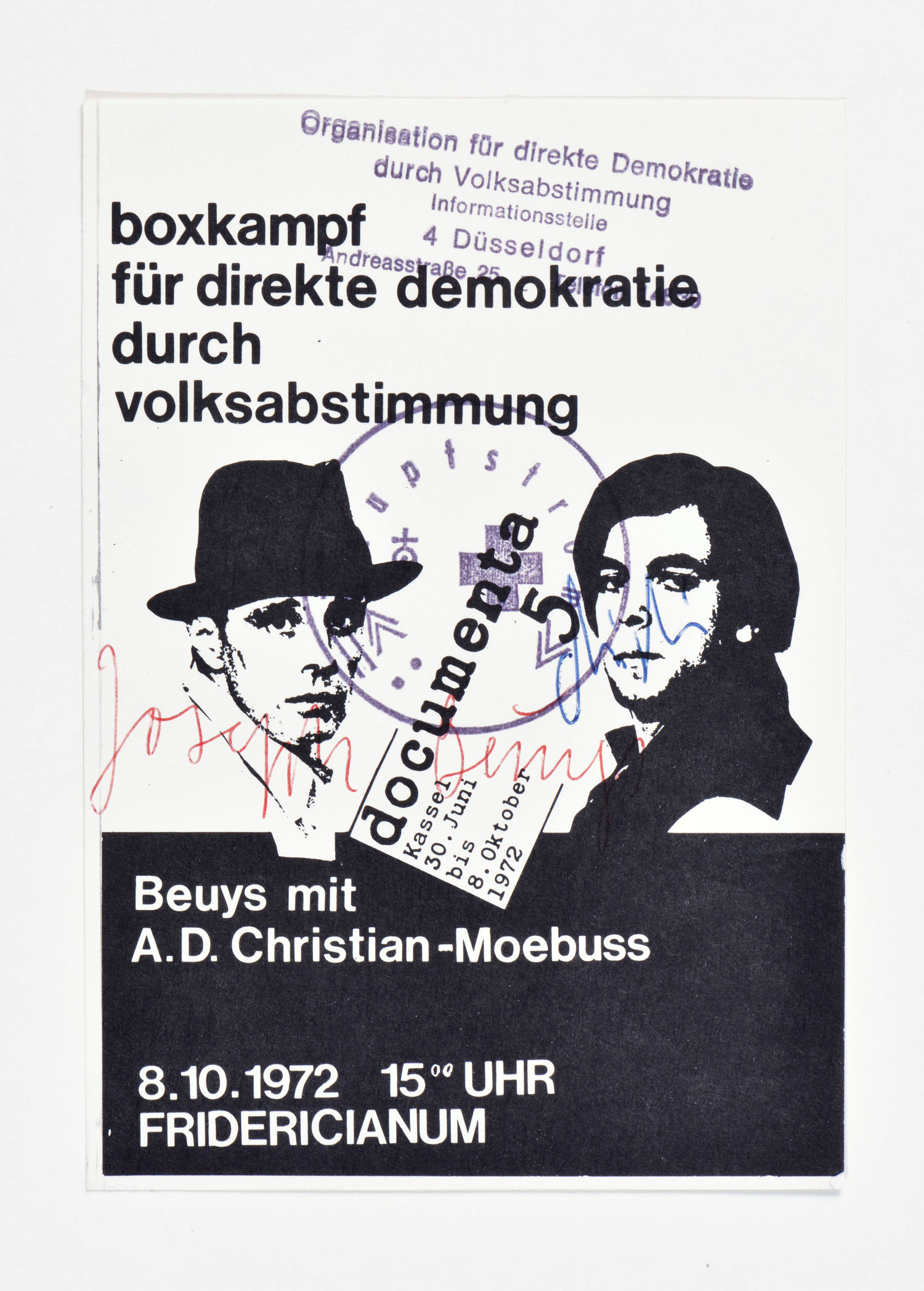

Beuys’s political commitment to the ideals of direct democracy and the founding of the Greens are just two examples (of many), reflecting his belief that as an artist he was a worker in service to society. Warhol’s art and his personality were also far more than just a mirror of his own metropolitan world. Both artists are like two sides of the same coin, representing the dawn of a new age in art, understanding not just their own but each person’s life as a work of art and thereby releasing enormous and (re)new(ed) forces in society as a whole.

Happy 100th birthday, dear ‘Jupp’! (as Beuys was dubbed).

The Museum Wiesbaden honours the exceptional artist Joseph Beuys with a diverse programme of lectures, immersive performances and talks. The Beuys 100 interventions will take place from 3 July to 12 October 2021 at Museum Wiesbaden and Schloss Freudenberg. You can find the programme in our calendar.

Watch our new video and get to know more about the Capri-Battery (1985)!

Translation: Lance Anderson