Dr. Jörg Daur, curator of modern and contemporary art. Background: Gerhard Richter, 'Terese Andeszka', 1965.

On leaving Soulmates, our guests are greeted by some big names in the history of German art. Almost as if they had been hovering around waiting for them, you might say!

‘The Early Years of the Old Masters’ was the brash title chosen for the recent show by the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, featuring works by Baselitz, Richter, Polke and Kiefer.

Yes, we also have early works by Georg Baselitz and Gerhard Richter on show here in Wiesbaden, not to mention some by Eugen Schönebeck and Jörg Immendorff, too. Now, when meeting and greeting, you should always go and join your guests where they’ve been left standing, literally and metaphorically speaking. In one sense, our guests find themselves in the gallery’s octagon; in another, they’re face to face with some of the ‘superstars’ of the West German art world. Personally, I can’t think of a better way to round off a visit to an exhibition on early modernist art…

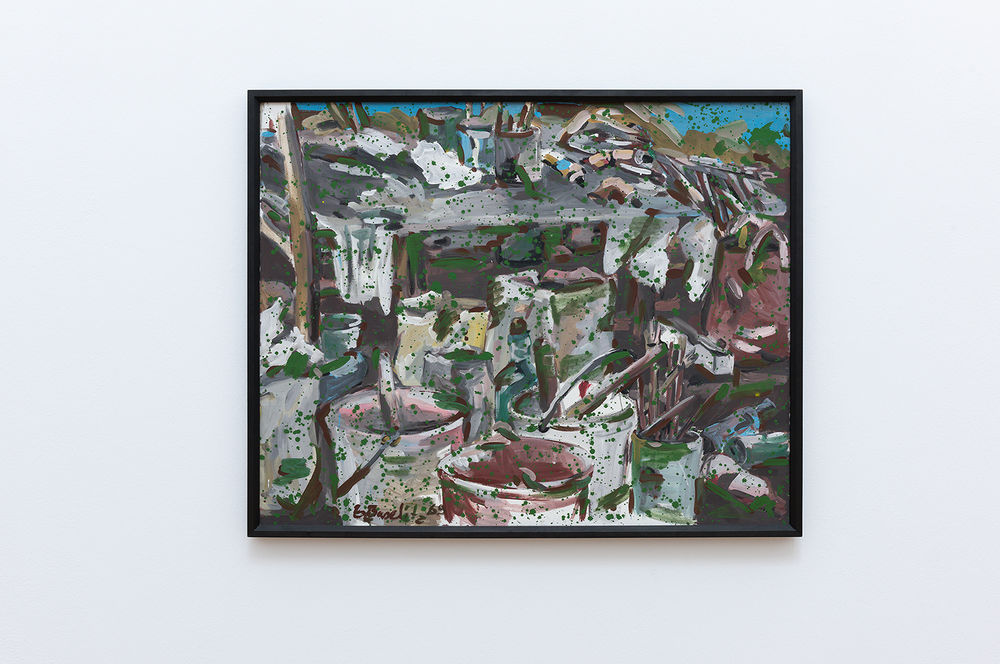

The younger selves of these four elderly gents do indeed offer an invigoratingly cocky re-examination of painting as an art form. Their early work was expressive, insolent, and perfectly of the moment. It also demonstrated a leap towards representation again – for in the immediate postwar years, the avant-garde had tended to favour the gestural abstraction exemplified by Art Informel, traces of which linger on in Baselitz’s still life. He has flicked green paint, apparently indiscriminately, all over his picture, so the splodges seem to hover over the representational image, partially obscuring it (possibly rejecting it?). At this stage in his career, he had yet to feel the need to paint his pictures upside-down or at least show them that way. Meanwhile, Schönebeck, a good friend of Baselitz, brings the horror of the Nazi regime into view. Not directly present in the image, it appears in the gesture of the head, its mouth bolted, unable to speak of the subject welling up within, needing to be vented.

There has been plenty said about Richter, so I’ll keep it brief and just draw attention to the black-and-white newspaper photograph he culled as a press clipping. The image, which went on to serve as the source image for Terese Andeszka, undergoes an odd transformation into painting, precisely because it abandons print legibility in favour of painterly gestures and qualities. Finally, Immendorff presents us with a Non-Swimmer, a figure in water who seems to sink almost intentionally, his fifties hat still firmly on his head. Could it even be a visual citation of Joseph Beuys, Immendorff’s teacher and mentor?

Leaving Immendorff behind, we enter the large gallery, where we encounter Andy Warhol, and, with him, American modernism. This may look like industrial painting – silkscreen printing – but has actually been painted over with the brush. Shadows appear as the subject of the picture, fleeting as the painterly gesture itself, but captured here in paint, preserved on canvas for all time. Warhol was another artist who sought a new start for painting. Like his 1960s German counterparts, he brings the ‘image’ – in a pop sense – back into paintings. At the same time, however, he was fascinated by repetition and seriality. American Pop Art runs parallel to an almost exactly contemporary movement: Minimal Art. This movement also set great store in repetition and clear and concise forms, but put even more emphasis on industrial production.

In the mid-1960s, Eva Hesse, located in the tense middle ground between the two movements, found her own path to a completely individual mode of expression. However, the groundwork for her ‘breakthrough’ into spatiality – and ultimately into the art market – was laid during her ‘year abroad’ in Germany, far from the New York art scene. Hesse had fled Germany as a Jewish refugee in 1938: her father was a Hamburg lawyer, barred from his profession by the Nazis in 1933. Some twenty-five years later she returned to Germany, albeit with profoundly uneasy feelings. Nonetheless, here she found the peace (and, moreover, the unwanted stock of a shuttered textile factory) that she needed to go beyond painting, using the relief to conquer spatiality. Along with this visual move came a turn to poetic titles: Eighter from Decatur oscillates between a wheel of fortune, a wind toy and bright-coloured nonsense object, apparently begging the spectator to keep it in motion… (But please don’t! No touching, remember you are in a museum!)

Instead, come with me to the next room on our tour, where we see more images from the 1960s, this time by Robert Ryman. Ryman’s small white squares, very finely painted on canvas, are characterized by reduction and concentration, revealing what is essential about painting as a medium. They are neither representational nor in gaudy colours; perhaps this is why they seem to come so close to the very core of painting. Without colour or form or even format to serve as a guide, every brushstroke and every application of paint gains clout. The other artists in the room are likewise working at painting’s core. Artists here range from Joanna Pousette-Dart, who uses form and the application of paint to experiment with visual space, landscape and light, to Joseph Marioni, whose compositions seem to wrest ever more facets, not to mention layers of colour, from their monochrome method.

tour. Here we can view the work of Otto Ritschl, a Wiesbaden painter whose paintings caused an international furore in the early 1960s. Exhibited as early as 1955, at the documenta in Kassel, his work connects with the colour field paintings of his American counterparts. Mark Rothko, among the most significant of this group, here offers a final insight into the history of painting in our time.

Jörg Daur

Curator of modern and contemporary art

Translated by Lance Anderson