Alexej von Jawlensky, Stillleben mit bunter Decke, 1910. Dauerleihgabe aus Privatbesitz

The Art Collections in the Museum Wiesbaden encompasses objects from the 12th century up to the present.You can have a first sight into the Old Masters, the Classical Modern and the Modern and Contemporary Art here.

Robert Seidel, Grapheme. ©VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018

The Old Masters collection encompasses works from the 12th to the 18th century, including religious and Italian art, as well as paintings from the Golden Age of 17th century Dutch painting.

The works of the collection are arranged thematically in separate rooms, allowing visitors to observe the development and echoes of a particular genre over time and even including contemporary works to enrich this experience.

Robert Seidel’s (1977, Berlin) installation Grapheme forms the entryway to the Old Masters exhibit. Like a tunnel, the room condenses and expands through the effects of color, reflection, sculptures, projections and sound, taking the viewer on an atmospheric journey to unknown worlds. The journey sets into motion several centuries of artistic expression through color, form and space. Seidel’s installation symbolizes the continual living presence of our cultural heritage.

On the second floor of the south wing of the building, designed and constructed by architect Theodor Fischer in 1915, the sculptures of the “church” have found a new home. In good historicist spirit, the octagonal central room lends the figures, once displayed in more sacred spaces, some of their original ceremonial quality back to them. Returning these objects to their home in the newly renovated “church” in 2013, the current presentation sustains this tradition.

The medieval wooden sculptures enter into dialogue with two contemporary works: MorgenAbend [MorningNight] by Micha Ullman and A Tale of the Sphinx by Katsura Funakoshi. The juxtaposition of old and new is intended to inspire visitors to become part of this dialogue. Only then can this “sacred” space be understood as a living organism.

Adjacent to the church, visitors will find an extensive collection of religious paintings, including some large-format Mariological and Christological panel paintings dating from the 15th to 18th centuries. These themes, for example, depictions of Christ, illustrate the dynamic relationship between religion and its visual representation.

The craquelé work of Frankfurt artist Jan Schmidt, inspired by the panels of the Heisterbach altar, illustrates that paintings are clocks without hands. They tick internally — their lifespan is limited, especially if they are wooden panels. A small network of fissures relates the history of their lives thus far. Like wrinkles in a human face, they bear witness to our present condition. Schmidt raises the transformed surface to an art and “paints” time.

The portrait room is devoted to Italian art. At the heart of the exhibit stands the portrait of Giulia Gonzaga, whose beauty is challenged only by that of Anselm Feuerbach’s Nanna, turning the portrait room into a gallery of “Italian beauties.”

The Golden Age exhibit is devoted to 17th century Dutch painting. This exhibit, unlike the other rooms, unites all of the themes — portrait, still life, landscape, mythology and religious art — in a single epoch, offering visitors a cross-sectional view of Wiesbaden’s uniquely varied collection of Dutch painting representing the full spectrum of possibilities in its “golden age” of the 17th century.

They are all taken up in Kazuo Katase’s Raum eines Raumes [Room in a Room]. Katase’s installation developed out of his thorough and attentive study of the museum’s 17th century Dutch painting. Katase, a Japanese artist who has made his home in Kassel, Germany, created this room especially for Museum Wiesbaden. The work opens a conversation with one of the most renowned Dutch artists of the Baroque period, Jan Vermeer van Delft (1632—1675), thematizing his unique approach to light and use of the camera obscura, questioning them anew through a complex staging of elements.

The Mythology room offers visitors a look into the world of ancient Greek myth, spanning from the seemingly harmless Putti playing with arrows in a piece by Francesco Primaticcio to the blatant eroticism of Sebastiano Ricci’s Danae and the dramatic binding of Prometheus in Luca Ferrari’s work through to more serene images by Pietro Liberis depicting Venus and her followers.

The Still Life room brings together various categories of still life painting, featuring motifs such as flowers, books, fish, fruit, musical instruments. These works attract our attention through their apparent yet veiled layers of meaning, provoking the viewer to reflection about suffering, transitoriness and death, while their moral and religious, even erotic, implications warn us of the decadence of excess.

The “final” room of Wiesbaden’s Old Masters exhibition displays the collections’ particular strength in landscape painting, one of the prominent genres of the Golden Age. As a counterpoint, the award winning film of contemporary artist Jörn Staeger (born 1965), Reise zum Wald [Journey to the Woods] transports us into the presence of current relationship to landscape.

With its presentation of the Old Masters collections, Museum Wiesbaden seeks to revise the notion of the museum as an institution issuing its “stamp of approval” to a site of communication and dialogue. This is a process of demystification of the museum, as such, but never of art.

The Museum Wiesbaden shows the collection of Ferdinand Wolfgang Neess as a permanent presentation in the south wing of the Museum Wiesbaden. The more than 500 objects form a cross-section of all genres of Art Nouveau and exemplify the quality and stylistic height of the art of the late 19th century. With the first presentation of the Neess Collection on June 29, 2019, the Museum Wiesbaden is exhibiting this outstanding collection to a broad public for the first time as a whole, thus putting Wiesbaden on the map of European Art Nouveau cities.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE COLLECTION FROM THE DONATION OF FERDINAND WOLFGANG NEESS

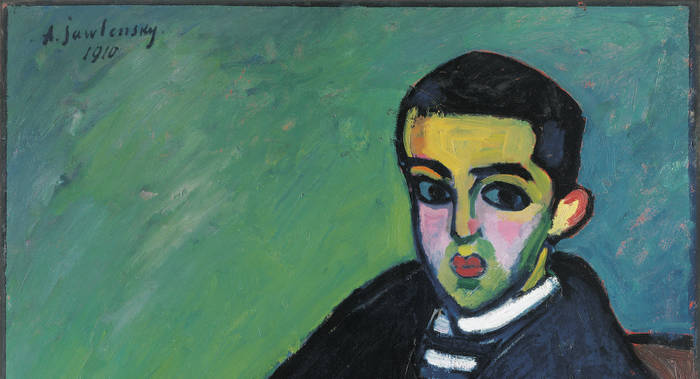

Alexej von Jawlensky, Nikita, 1910. Museum Wiesbaden

The museum’s Classical Modernism collection holds international significance, above all, for its assemblage of over 100 works by Russian Expressionist Alexej von Jawlensky (1864—1941), who spent the last twenty years of his life in Wiesbaden.

Jawlenky’s work complex forms a central focus of the museum’s collections. Though Jawlensky was the city’s most prominent “local” artist from 1921 until his death in 1941, the museum’s collection of his work is by no means a simple consequence of his close relationship to the city. The museum’s initial collection of Jawlensky works, built up in the late 1920s and early 1930s, was purged entirely between 1933 and 1937 as a result of National Socialist cultural politics. All of the works in the museum’s initial collection were either returned to their previous owners or removed from the premises.

The museum’s Jawlensky collection today has been rebuilt through strategic acquisition over the last 25 years and now encompasses over 100 works, making it, alongside the holdings of the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, one of the largest and most significant Jawlensky collections worldwide.

The works in this collection represent all of the major phases of development in the artist’s career — the early Munich period, the Murnau and Schwabing period, exile in Switzerland and the formative Wiesbaden years. Moreover, the collection contains a number of his multifaceted graphic works of exceptional quality, including self-portraits, portraits and landscapes. On the occasion of the reopening of the museum’s newly renovated central wing in 2006, another significant work, The Redeemer’s Face (1921), was added to the collection. The acquisition was made possible in cooperation with the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation, as well as through the generous support of the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States, the Cultural Foundation of Hesse, the City of Wiesbaden, the Hessische Landesbank, the SV Sparkassenversicherung Hessen-Nassau-Thüringen and the Naspa-Foundation Initiative and Effort.

Jawlensky’s infamous Helen in Spanish Dress was given to the museum in 2014 on the occasion of its commemorative exhibition marking the artist’s 150th birthday. This major work was a gift by local collector Frank Brabant, an avid collector of the works of the “lost generation” of Expressionists since the early 1960s, who has frequently supported the museum by lending works from his Classical Modernist collection for display.

The significance of the museum’s Classical Modernism collection was augmented in 1987 with the addition of the Hanna Bekker vom Rath collection, containing works by such noted Expressionists as Ernst Barlach, Lovis Corinth, Lyonel Feininger, Natalia Gontscharowa, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Otto Mueller and Emil Nolde, as well as major works by Willi Baumeister, Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

Hanna Bekker vom Rath was a collector and art dealer whose “blue house” in Hofheim in Taunus served as a refuge for many artists labeled “degenerate” by the Nazi regime. Some 30 highly valuable paintings and drawings were purchased from her estate by the Society for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Wiesbaden and have been made available on permanent loan to Museum Wiesbaden.

This second focus of the Classical Modernism collection encompasses works by Ella Bergmann-Michel, Erich Buchholz, Walter Dexel, Adolf Fleischmann, Werner Graeff, Robert Michel, László Moholy-Nagy, François Morellet, Anton Stankowski and Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart.

Constructivism forms an important part of the history of Modernity in Wiesbaden’s art collections, insofar as the “circle of new commercial designers” was established here in Taunus in 1927. The works of artists from this circle, as with those of the Expressionists, were labelled “degenerate” by the National Socialists and eradicated from museums across the country. The first cornerstone of the collection’s Constructivist focus was laid in the years immediately after the Second World War with the acquisition of works by László Moholy-Nagy, Walter Dexel and Erich Buchholz.

By contrast to the Jawlensky collection, there was little expansion to the museum’s Constructivist focus in the 1950s. It was not until the 1990s that genuine expansion occurred when the Vordemberge-Gildewart Foundation in Switzerland bequeathed its vast archive of the Constructivist artist’s works to Museum Wiesbaden. Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart (1899—1962), who in the 1920s was invited by Theo van Doesburg himself to become a member of the de Stijl group, left behind an estate encompassing some 50 000 drawings, typographic works, studies and guest books, as well as numerous sketches, photos, letters and other papers belonging to his a circle of friends and acquaintances, such as Kurt Schwitters, László Moholy-Nagy, Theo van Doesburg. The bequeathal of this extensive material has made Wiesbaden one of the most important sites of Constructivism in Germany.

In 2006, with the reopening of the museum’s central wing, ten reconstructions of early reliefs by Wladimir Tatlin (ca. 1915) were put on permanent loan to the museum by Annely Juda Fine Art. These pieces are considered incunabula of the Russian avant-garde and of modern sculpture, now fittingly displayed in the direct vicinity of Ilya Kabakov’s “total” installation The Red Railroad Car (1991), creating a perfect segue to the art of the second half of the 20th century.

Mario Merz, Spiral Table with Igloo. Gambe che corrono/1988/95, 1980. ©VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018

Art of the European and American Modern period after 1945 forms one of the most prominent collections of the museum. The collection focuses on abstract painting and sculpture concerned with the thematics of line, color, surface, volume and space.

Today, the museum’s collection of Modern art after 1945 belongs to the most prominent of its collections. It features international figures of Abstract Expressionism such as K. O. Götz, Gerhard Hoehme, Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt, while works by Georg Baselitz, Jörg Immendorff and Gerhard Richter, as well as by Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Dieter Roth and Eva Hesse, one of the most significant female artists of the 20thcentury of whose oeuvre Wiesbaden holds 12 works, offer a strong showing of artists from the post-war period in Germany.

Installations by Jochen Gerz, Rebecca Horn and Ilya Kabakov, as well as works of American Minimal Art complete the collection. Similar to the way these artists relate to Constructivist positions of the first half of the 20th century, we can see the examination of color that began in Expressionism being taken up as a fundamental element in the work of painters like Otto Ritschl, Ulrich Erben and Raimund Girke.

The commitment of the city of Wiesbaden and the museum to an active dialogue with the most important currents of international art is reflected in the establishment of the Alexej von Jawlensky Prize, awarded every 5 years in honor of the Great Russian painter. The prize is associated with a cash award, an exhibition in Museum Wiesbaden and the purchase of work for the museum’s collection.

The prize is funded by the city of Wiesbaden, the Spielbank Wiesbaden and the Nassauische Sparkasse. The support of these three institutions signals their recognition of and commitment to the creative energy Alexej von Jawlensky contributed to the cultural life of our city.

First to be awarded the prize was American painter Agnes Martin in 1991, followed in 1996 by American painter Robert Mangold, selected by an international jury as the second recipient. In 2003, the prize went to the American painter Brice Marden, who accepted the award in 2004 at the opening of the exhibition “Jawlensky — My Dearest Galka!” In 2007, the prize was awarded a fourth time to the artist Rebecca Horn, whose work has been shown at multiple documenta exhibitions. The award ceremony in March 2007 marked the opening of not only the Horn exhibition associated with the prize but of her mirror installation “Jupiter in the Octagon.”

In 2010, the American artist Ellsworth Kelly was awarded the Jawlensky Prize for his life’s work. The award for exceptional contribution to the fine arts was presented at the opening of the artist’s exhibit associated with the prize in March 2012.