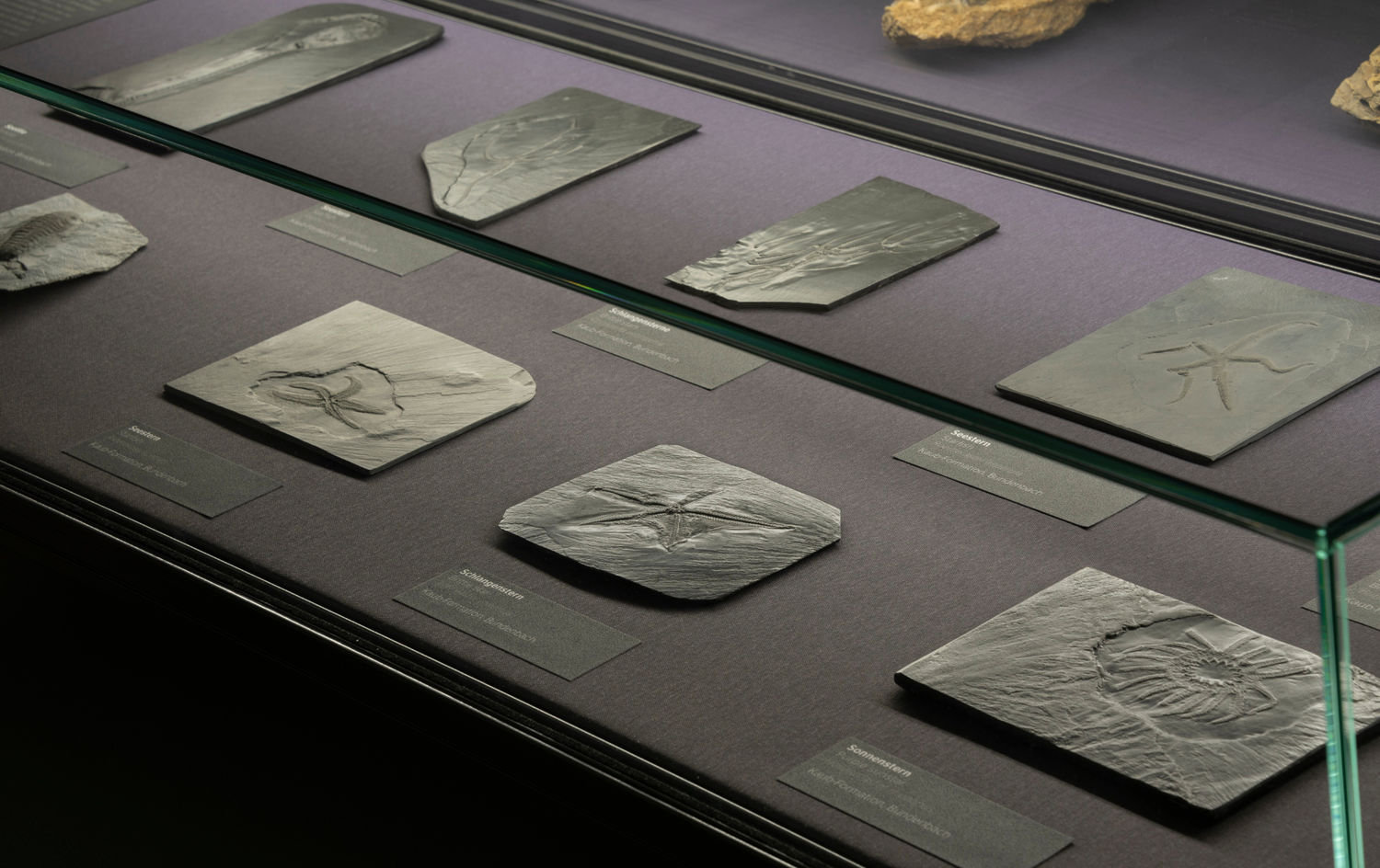

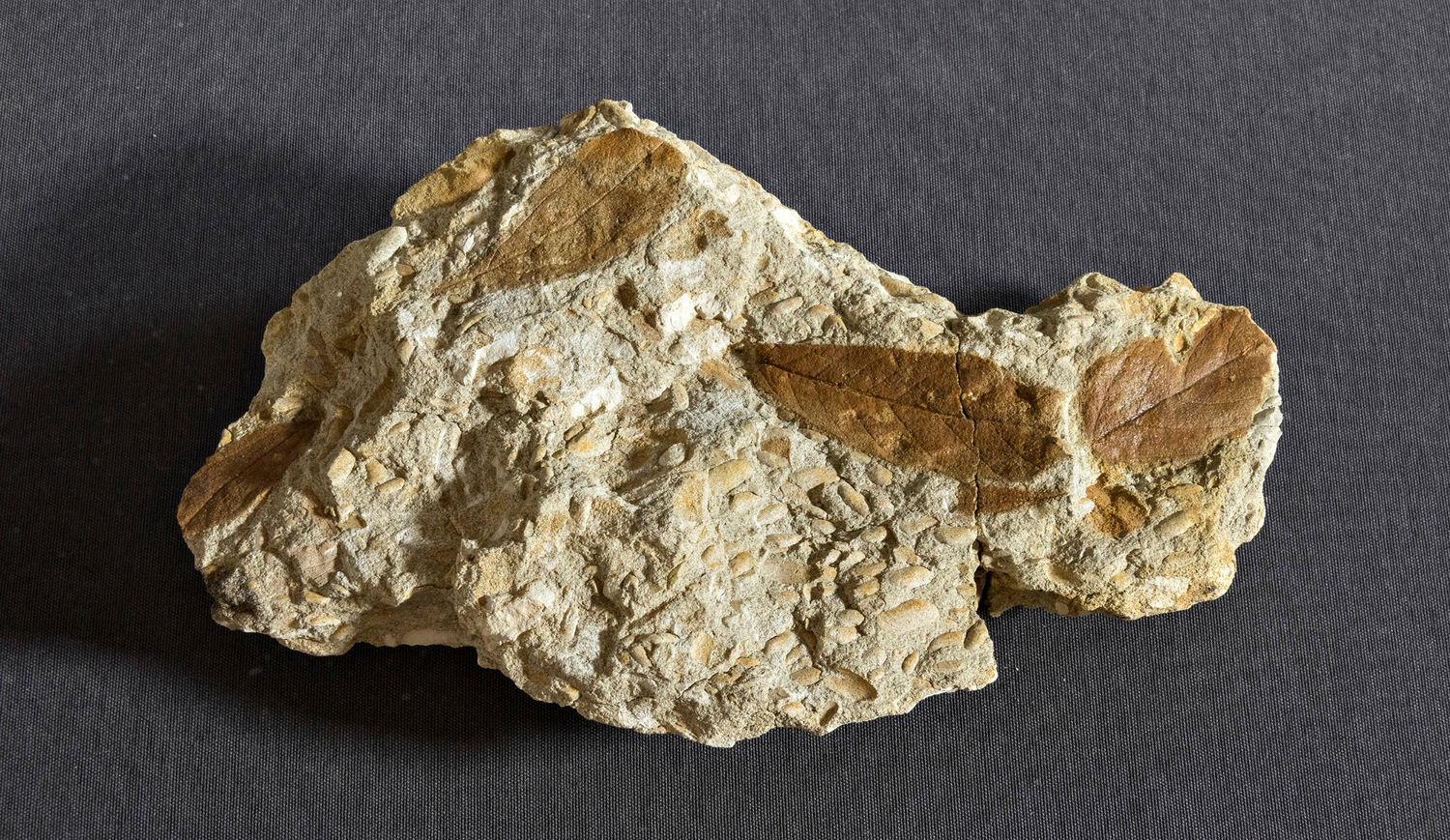

Fossils from the region provide insight into the evolutionary history of contemporary plants and animals. Four-hundred million years ago, when Hesse was still a great sea, it was populated by sponges, coral, sea lilies, mussels, snails, and squid. Specimens of now extinct trilobites and armored fish testify to life in the Paleozoic era. By the Tertiary, the world again looked entirely different. Sharks hunted manatee in shallow seas. Swamplands provided habitat for crocodiles, turtles, fish, and frogs. The fossil remains of this plant and animal world stem from the 12– to 38-million-year-old deposits of the Mainz Basin, a marine basin that once covered the present-day Rhenish Hesse region.

Younger sedimentation from the ancient Main river and the Lahn Hallow contained mammoths, forest elephants, hippopotamus, hyenas, deer and bears. The oldest of these fossils are some 890,000 years old, the youngest 20,000. In this period, symbiotic communities were shaped by a number of drastic changes in climate. Thermophilic species like the forest elephant were not contemporaries of the Tundra mammoth. Early humans of the Ice Age recorded images of their life world with great artistic skill in cave paintings.

The state of fossil preservation, their rarity, and the vast gaps between their occurrences or to their closest relatives form the questions of Paleontology. The urban area around Wiesbaden is a case in point. From the Rhine to the first ridges of the Taunus stretches a depression filled with sands, gravels and loess that continues to descend with the Upper Rhine Plain. In the gravels and sands there are fossils from the recent past, the age of climate change, and the Quaternary. Missing from them, however, are the sediments of several million years that have been removed by wind and water. In Wiesbaden’s quarries, there are limestones from marine deposits dating back to about 20 to 30 million years ago, and the shales of the Taunus testify to the existence of an ocean about 380 million years ago.

The eventful history of the Mainz Basin in the Tertiary period makes for a particularly exciting highlight of the Wiesbaden exhibition. As early as the 19th century, the fossil discoveries of the explorations of this lost world by the Sandberger brothers became known around the world. Some 31 million years ago, the area was covered by a subtropical sea that ended in the south near Basel. At the same time, gravels and sands formed on the coast, belonging to the Alzey Formation, and containing countless fossils. Numerous ecological niches are filled by corresponding marine species. The sea was warm, up to 180 Meters deep, and populated by sharks and their prey, such as tuna and manatee. The latter fed on sea grass growing on the shallow sand and gravel shores. In the course of millions of years, the sea became increasingly shallower and the connection to the northern sea was cut off. Some 24 million years ago between the Upper Rhine Plain and the Mainz Basin, a barrier of algae reefs and a shallow lagoon was formed. The resulting limestone served as the source for cement production in the region until recent times. The increasingly brackish environment promoted the growth of some mussels and snails, which, though few in species, appeared in such masses that, by the millions, they formed so-called hydrobial layers.

Loading …

We are already planning new dates for this event! In the meantime, check out our calendar to see other exciting offers.

Museum Wiesbaden offers a variety of programs for all ages, from guided tours to workshops for preschools and schools, to teacher training and programs for students, private groups, or families with children.