August und Elisabeth Macke, 1908. Photo: Museum August Macke Haus, Bonn

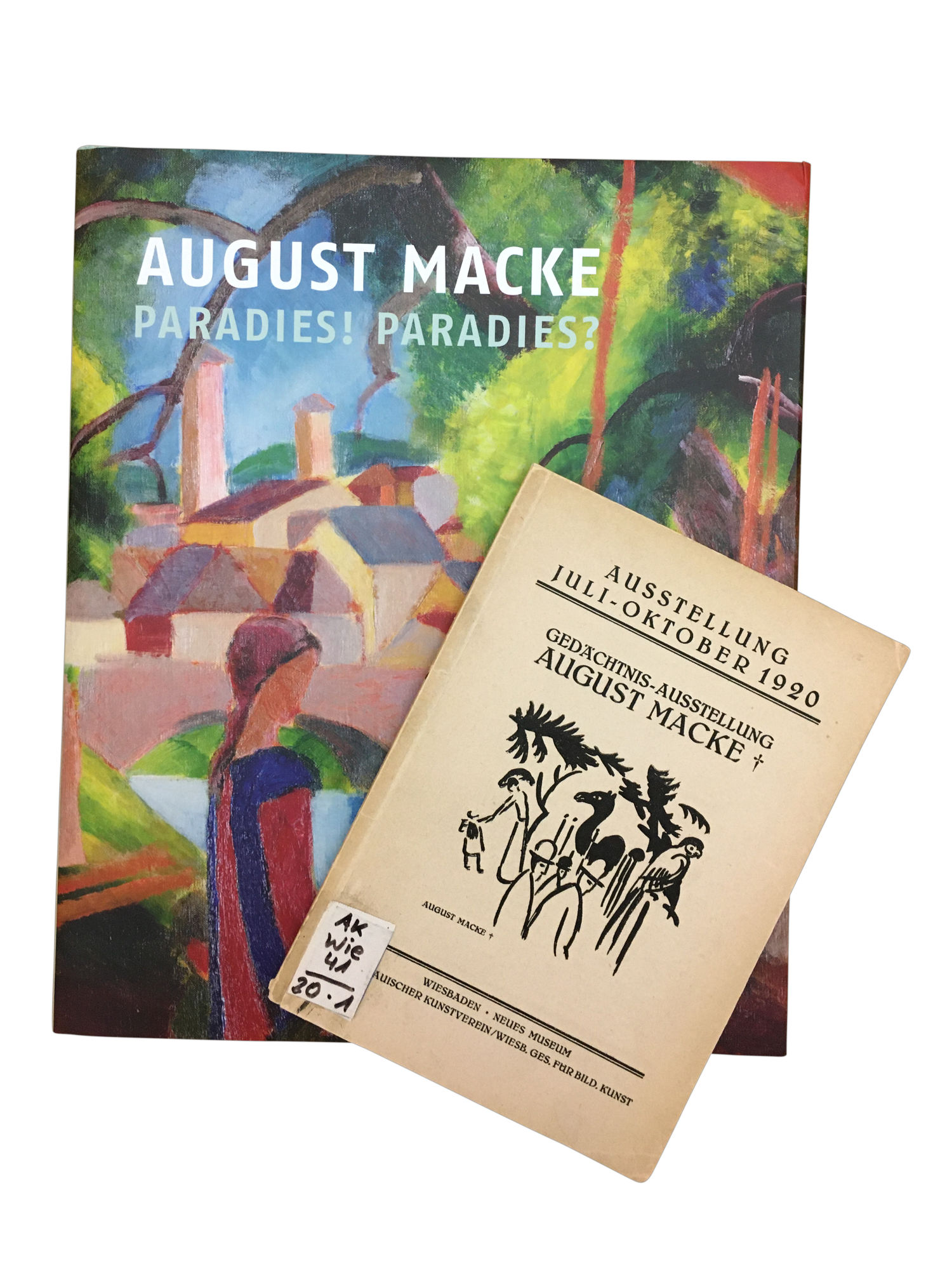

The present exhibition Paradise! Paradise? is nonetheless not a rigid reconstruction of the memorial exhibition but rather seeks to echo the character of the original, for example by displaying paintings representing each of the groups of works shown in 1920. There are the watercolours of the famous journey to Tunisia (1914), the paintings from his Munich period (1910) and those made during his stay in Hilterfingen (1913) on Lake Thun in Switzerland. Then there is his intense study of the art of his time, where one can sense that the Fauvist painter Henri Matisse acted as a catalyst, just as Vincent van Gogh did for Jawlensky or Paul Gauguin did for Werefkin. Every artist seeks a different point of contact to step out of the shadows of history.

The third level – one that we greatly cherish and one that brings us and hopefully you as well a great deal of joy – may actually be the key to understanding August Macke the artist. It is the section devoted to his wife, Elisabeth. It was Elisabeth who made the Memorial Exhibition one hundred years ago possible, supporting it in important ways. This is why we were determined to include her in the exhibition, framing her in the context of her relationship with the artist (whom she met at the age of just 15). Macke nicknamed his wonderful painting Artist’s Wife with Hat ‘Mona Lisa’, not only as a gesture of affection to his beloved Elisabeth, but also to indicate its iconic status in his oeuvre. Originally planned as a half-portrait, Macke kept cropping it until it reached the version we see today – sacrificing stature in favour of a more intimate view of the sitter. That’s the way it always is, after all: you don’t relinquish anything voluntarily unless there is something to be gained in return. There is scarcely another portrait from the first half of the 20th century that bears all the hallmarks of modernism and yet is as touching as this ‘Mona Lisa’.

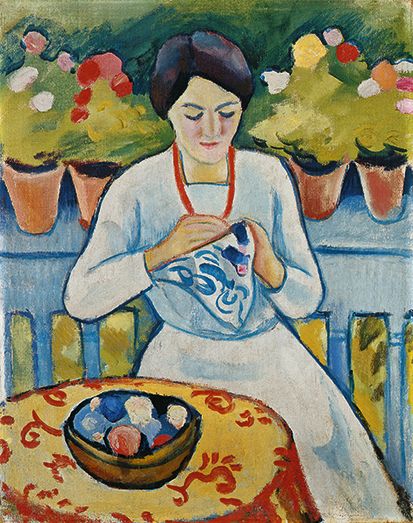

Directly adjacent is another view of Elisabeth, Woman Embroidering on Balcony. Here we have the quintessence of everything in Macke’s visual world that mattered to him. In the centre of the painting sits his beloved wife, so absorbed in what she’s doing that she is oblivious to everything and everyone around her. Sitting at a round table in front of the balcony railing in a white dress, with lowered eyes, rosy cheeks and just a hint of a smile, she quite naturally forms the main focus of the painting. The red outline of the table, which corresponds with her necklace; the pattern of the embroidered tablecloth and the coloured balls of wool in the bowl, alluding to her meticulously executed handicraft; the arrangement of the four flowerpots, their blossoming flowers framing her head – all of this firmly embeds the young woman, a delicate being, in surroundings akin to the paradise that August Macke created for himself and for his art and knew how to use to good effect. The painting thus spans Macke’s entire artistic and intellectual horizon. Enhanced by the all-pervasive feeling of security suggested by the composition, Elisabeth symbolises the safe haven of family life. At the same time, with reference to Henri Matisse’s then-latest works, Macke also takes up the theme of ornament as a bridge between abstract art and its potential for the applied arts.

Which brings us back to the first level, where our exhibition includes two colourful ornamental designs for planters. Perhaps easy to overlook, the effect of these joyous designs is so enlivening that you could be forgiven for thinking that Macke has added a secret formula, a fertilizer, for the plants they are supposed to contain. The standard terracotta planters are transformed under Macke’s brush into a paradise for even the most ordinary of potted plants.

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger

Kustos Classical Modernism

Translation: Lance Anderson