As of today, 12 May 2020, Museum Wiesbaden is open again to visitors – and there is a pent-up longing to see particular exhibits.

What are visitors looking forward to most? What objects have they been longing to see?

There was a great response to the invitation by our museum director Dr. Andreas Henning in his Easter circular to write in and tell us which objects our visitors were personally missing the most. In this contribution to our blog ‘Objects of Longing Part II’ we’d like to share some of the many emails we received. Many thanks to members of the Freunde des Museum Wiesbaden for their inspiring posts!

The sculpture A Tale of the Sphinx in the museum’s Church Hall

Whenever I’m in the museum, I go to see the sculpture by Katsura Funakoshi in the Kirchensaal, ‘A Tale of the Sphinx’. This female figure carved in wood is delicate yet strong at the same time, present yet withdrawn. In the Kirchensaal, she is surrounded by wooden statues that are hundreds of years older than herself, each made for a particular ecclesiastical setting. ‘A Tale of a Sphinx’ doesn’t let that bother her; she neither relates to her surroundings nor holds herself aloof; she simply remains herself. I can’t think of any other spot in the museum that would suit her better. I’m fascinated by her presence, her concentration, her inwardness. I may have brought issues with me from my everyday reality and found them reflected in other exhibits, whether in the permanent displays or a particular special exhibition, but in her presence they simply fall away. She has something unique and intense about her, which she offers me but doesn’t impose on me. I remember the wonderful exhibition in 2015 when the Wiesbaden Sphinx was surrounded by other figures by Funakoshi. It was exciting to see how the individual sculptures linked with and related to each other. The wonderful illustrations in the exhibition catalogue capture this impression of thematic density. For me, no trip to the museum is complete without a quick visit to this statue, so for me this is a place of longing in ‘my’ museum.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Helene in Spanish Costume, 1904

I keep being drawn back to my absolute object of longing in the ‘Soulmates’ exhibition. My favourite painting in the show is the life-size ‘Helene in Spanish Costume’ (gifted to Museum Wiesbaden by Frank Brabant). Even Helene’s background story is fascinating. She was a maid employed by the painter Marianne von Werefkin, who lived with Alexej von Jawlensky for 29 years. In 1902 Helene gave birth to her son Andreas, her only child. Jawlensky married her and moved with her to Wiesbaden, to a house on Beethovenstrasse. What a lovely real-life story about a larger-than-life artist and free spirit.

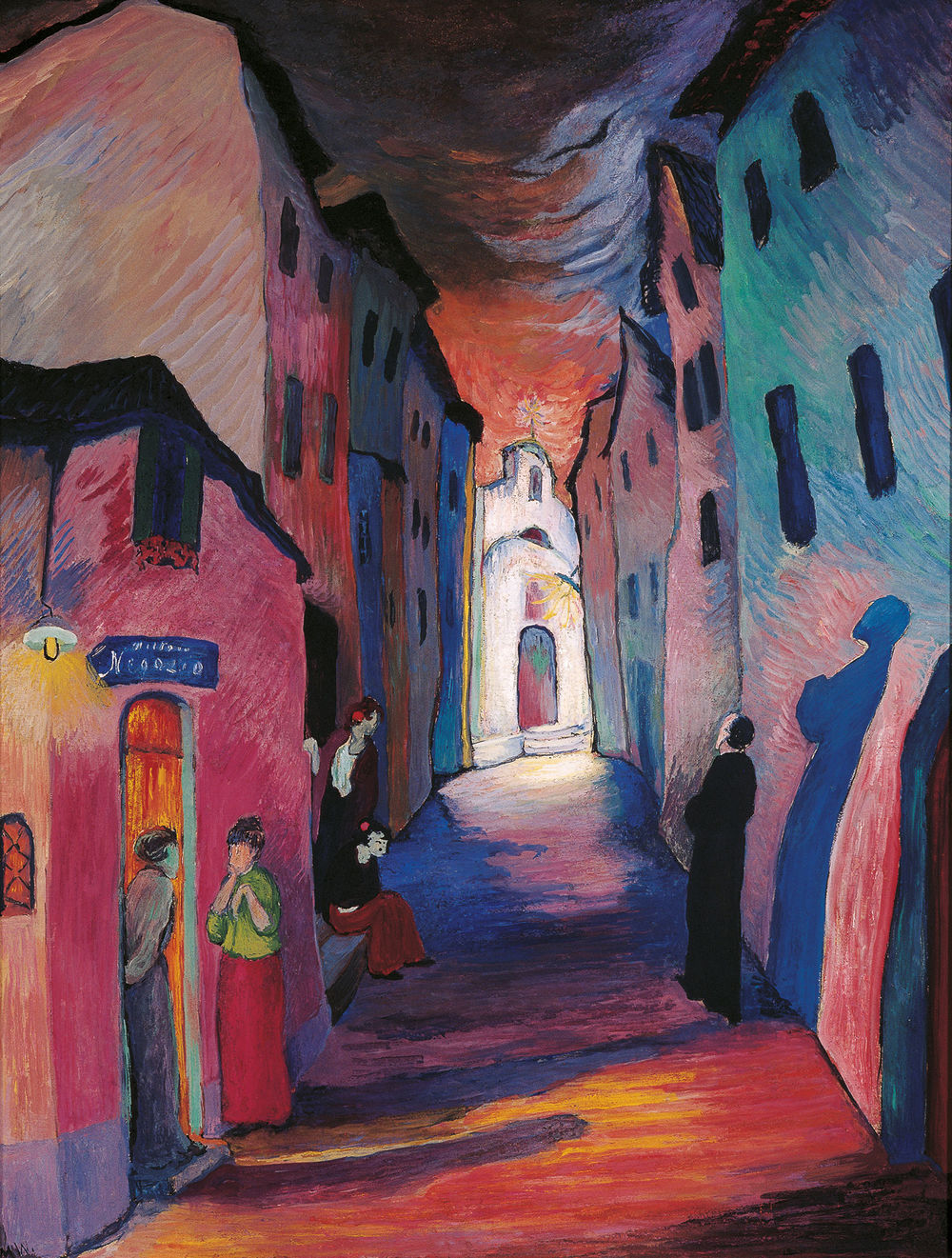

Marianne von Werefkin, Ave Maria, 1927

‘Helene in Spanish Costume’ will just have to wait. Though she’s normally my favourite, this time she’ll have to step aside for another picture, one painted by her former employer and mistress of the house. As soon as the museum reopens, I’ll be rushing straight to Marianne von Werefkin and sinking myself into her painting ‘Ave Maria’. Enigmatic, mystical, one of those ‘street’ motifs, where you long to know where the street is leading. Associations with Expressionist silent movies, displaced worlds in garish colours.

Max Beckmann, Female Nude with Dog, 1927

My object of longing is Max Beckmann’s ‘Female Nude with Dog’, which I was thrilled to find back in its old place last autumn, in the rear gallery. I saw the painting for the first time in a Beckmann show at Tate Modern in London. When I moved to Wiesbaden in 2002, it was a huge joy to discover that it belonged to the museum collection of my new home-town. Since then it’s become a friend I like revisiting again and again. Unlike the many ‘dark’ and sometimes rather theatrical Beckmann paintings, I love the lightness of this one, its relaxed atmosphere and upside-down composition. It always conjures up a smile. To make sure the longing doesn’t become too overpowering, I’ve temporarily hung the museum poster featuring this painting on my wall, but I’m still greatly looking forward to a reunion ‘in the flesh’.

Robert Seidel, Grapheme, immersive walk-in installation, 2013

My object of longing is the installation ‘Grapheme’ by Robert Seidel in the anteroom to the Old Masters. I find this a very successful solution to what is actually quite a problematic space. The mirror wall draws you in, so that you immediately become part of the installation yourself; its buoyancy stimulates your imagination and instantly puts you in a good mood. It has a dance-like quality that never fails to enchant. Moving on into the first gallery of Old Masters there are other objects of longing, but this one comes first.

Jean Delville, L’Oracle à Dodone, 1896

My favourite section of the museum is the marvellous Jugendstil collection. On my many visits, I’m especially drawn to the Symbolist paintings and particularly to ‘Loracle à Dodone’ by Jean Delville. Its enigmatic quality never fails to fascinate me, and I always find myself standing in front of it, trying to discover something new, so I may as well simply designate it my ‘object of longing’ without further ado. I completely go along with the art-historical facts about the painting and the interpretations of certain motifs and details offered in ‘Ruf des Progressiven’, published by the museum (page 94). In addition, however, a great key to unlocking the painting is the symbolism of the right-to-leftness of the pose (conscious-unconscious/male-female/present-past/real-unreal, etc.). With some training in art psychology myself, I have often used the direction in which the picture is read as a way of approaching art in my courses and tours for art lovers. This viewpoint and emphasis, however, receives hardly any attention in the scholarly treatment and interpretation of paintings. Probably it’s omitted because it’s seen as too self-evident. In my view, it’s an essential factor in what makes a picture be described and experienced as ‘beautiful’ and is a valid subject of rational discussion just as any other aspect of pictorial technique. The various personal responses to my ‘longed-for painting’ can only happen in front of the actual picture itself.

Gerhard Richter, Queen Elizabeth, 1967

I’m already looking forward to paying homage again to Gerhard Richter’s timeless ‘Queen’. She simply radiates calmness and serenity, coupled with hidden humour and inner strength (in other words, just what we need right now!). With this painting you really feel that art has the capacity not only to depict external appearance but to capture a person’s essential being. People may change outwardly, but inwardly they remain the same. Especially today, it’s comforting to think that some things will still be the same after the crisis as they were before.

Donald Judd, Seven Cubes installation, 1973

Particularly in times of the coronavirus, there is a great longing for movement. Donald Judd’s installation doesn’t just allow movement, it demands it – movement both physical and mental. At first the blocks simply stand there, side by side, but as you begin to move through the room, they change. Right angles appear, straight lines become diagonals. At a distance, they give the impression of being hip height, but go up close and you can disappear in them. The whole installation changes, depending on your perspective, always creating some new and fascinating prospect. Donald Judd’s installation is something I’m definitely looking forward to seeing again.

Conrad Felixmüller, Autumn Flowers with Cat II, 1922

When the museum opens again, I’d like to spend time contemplating Conrad Felixmüller’s ‘Autumn Flowers with Cat II’ again. The cat is curled between the flower vases, completely relaxed. The painting radiates peace and creates a lovely atmosphere. The colours are wonderful too. The work was painted during Felixmüller’s best period, in 1922. I have a few paintings by Felixmüller in my own collection, including some from this stage of his career, for example a portrait of his friend Hermann Kühn from 1923. Kühn was a teacher at what is now the European Centre for the Arts at Hellerau. It’s nice that we at the Freunde des Museums Wiesbaden helped purchase the Cat in 2017.

Katharina Grosse, Seven Hours, Eight Voices, Three Trees, 2015

Whenever I visit Museum Wiesbaden, I’m drawn as if by magic to the work by Katharina Grosse ‘Seven Hours, Eight Voices, Three Trees’, created by the artist for her exhibition at the museum in 2015. What a magnificent, intoxicating intensity of colour! There they lie, those mighty tree trunks, felled by a storm and flooded with colour, and seem to transform the classical order of the Säulenhalle into a jungle-like primaeval forest! And the impression is further heightened by the huge lengths of fabric, soaked in colours, filling the room like a tropical flood – you almost believe you can hear the rustling of primaeval trees. For me, this installation exerts a powerful attraction: I always feel captivated, intoxicated, and enriched by it.

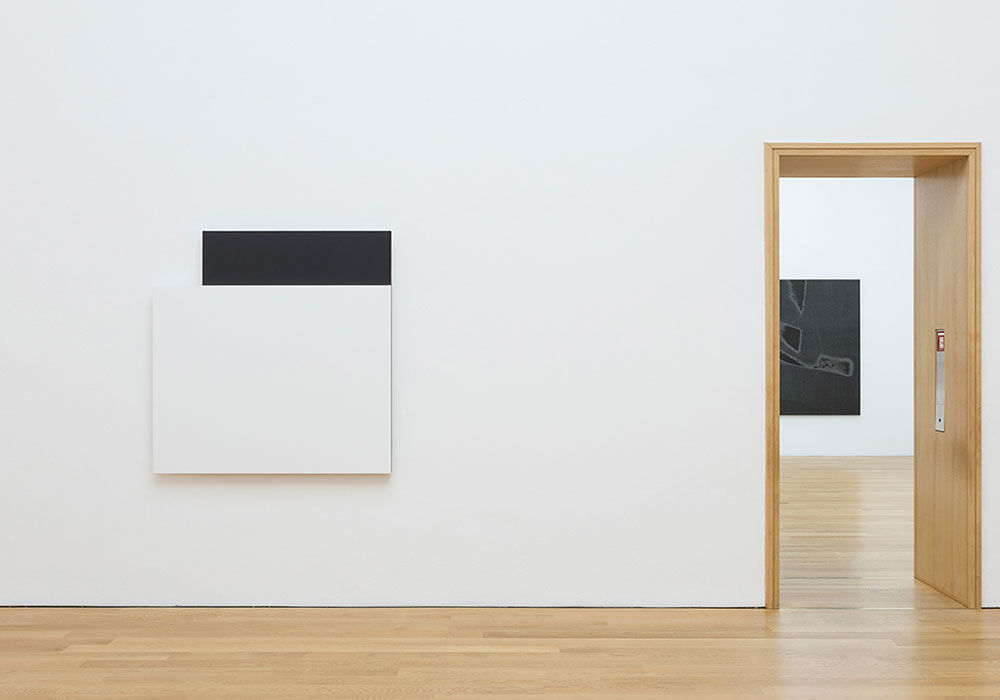

Ellsworth Kelly, White Relief over Black, 1963

I love the diversity of Museum Wiesbaden. But I particularly enjoy looking at works with concrete shapes and clear colours. That’s why I often go round the collection of European and American post-war art. It’s the rectilinearity of many of the works that fascinates me, just as it’s this quality I like best in architecture. So when the museum is open again, I will definitely be drawn to ‘White Relief over Black’. The Jawlensky Prize winner Ellsworth Kelly created it in 1963 and I think it’s wonderful that it was purchased for the museum with the help of the Friends.

The Museum Wiesbaden as a Place of Longing

When I heard about the ‘Object of Longing’ initiative at Museum Wiesbaden, I had to admit that, for me, there’s no one special object. I’m longing for the museum as a whole: the architecture of the building, the sounds, the smell, the people – in a word, everything that makes the museum what it is.

When I think back over my museum memories, a picture from the Knaus exhibition comes to me, whose title I can’t now recall. It’s a scene in a barn with a travelling entertainer or musician and dozens of people crowding round. I remember that this scene radiated pure joie de vivre and I felt I could almost smell sweaty clothes and dusty straw. And there’s another ‘image’ which comes to my mind’s eye. I can just picture the film sequence with the dancer Loie Fuller, part of the Jugendstil exhibition. Loie Fuller (1862–1928) created the Dance of the Seven Veils. For her personally it was physically exhausting and extremely painful, but there’s no hint of that in her breath-taking performance. The same dance-like grace and playfulness can be found in many other objects in this exceptional exhibition. Its huge variety, with over 500 exhibits, means that you can always discover something new and fascinating.

Rebecca Horn, Jupiter in the Octogon, 2007

I’ll be heading for the entrance foyer, to where all museum visits begin – with the wonderful work by Rebecca Horn, ‘Jupiter in the Octagon’. The mirror installation was created by the artist especially for this site and it has been enthralling visitors since 2007. A contemporary work moving with technological precision, it nevertheless fits timelessly into the octagonal room that Theodor Fischer designed in his venerable museum building, with its historically and regionally influenced architecture. But although it is in complete harmony with the architecture, its mirror-cabinet effect superimposes unreal-seeming shards and circles – depending on your perspective – on the golden cupola, the sky or the octagon, calling into question your sense of space and the feeling of your body-in-space. Its central location means that while wending your way round the museum, you can always look forward to another encounter with the mysterious installation on your way out – and, in all probability, to discovering more aspects of this multifaceted artwork. If only I could be back in this special place today!

Micha Ullman, NachTag, 2006

It was a strange situation, knowing about Museum Wiesbaden and its treasures and not being allowed to go there. I missed something important to my way of life, a pleasure I’ve hitherto taken for granted: being in a place where I can quietly experience creative stimulation, beyond the reach of the day’s events and superficial priorities. How does Museum Wiesbaden manage to offer this peace and stimulation? Yes, there are highlights which particularly touch and move me. Among the artworks these are, for me, Jawlensky’s variations on the view of his garden, while in the Natural History Collections I’m fascinated by the colours, forms, and movements by which nature reveals herself as the supreme creator. It is precisely this interrelationship between art and nature which never fails to create, for me, that experience of stimulation I would not like to be without. But, over and above the highlights, I enjoy the special atmosphere of Museum Wiesbaden itself, which envelops me as soon as I step into the entrance octagon with Rebecca Horn’s disconcerting reflections – now with a thrilling pendant in the ‘Daynight’ floor sculpture by Micha Ullman.

Louis Eysen, Blossoming Tree

When I’m allowed back into the museum – hopefully soon – I’ll be going for another look at the wall of paintings by Louis Eysen. My favourite is the wild rose tree. Almost no other German Impressionist handles the colour green so brilliantly, and here it’s combined with pink blossoms – the painting technique is simply exquisite. Most of the Eysens are actually on permanent loan from a private owner, but this is still one of the few large collections of Eysen’s paintings anywhere in the world – a hidden treasure.

Mussels, Mussels, Mussels

Two of our younger museum Friends – aged 7 and 8 – also confided to us their object of longing. They wrote: ‘We like going to see the mussels, because they remind us of lovely holidays at the beach.’

Luca Ferraris, The Binding of Prometheus

Once lockdown ends, I will look at Luca Ferraris’ ‘Prometheus’ with new eyes. To my mind, the scene dramatically reflects humanity’s situation during this crisis. Prometheus in chains, the longing, almost imploring backward look at supposed mistakes, and the anxious question – how will it all end? A warning allegory of fate.

Rebecca Horn, Circle of Broken Landscape, 1997

I’m continually tantalized by the possibility of experiencing her other installations in Museum Wiesbaden: waiting for the ‘Circle of Broken Landscape’ to begin to move, for the feathers ‘In the Circle of the Eagles’ to splay. The installations by this many-facetted artist expand space and broaden the imagination of the viewer. This was what I had in mind when I commissioned Rebecca Horn to create just such a space for an opera production at the 2010 Internationale Maifestspiele – Richard Strauss’s ‘Elektra’. It was a very interesting artistic encounter with this exceptional artist from the Odenwald!

Joseph Marioni, Red Painting, 2000

At first sight, this picture looks completely dark, almost black and certainly not red. It’s only when you shift your gaze from the centre of the picture and begin to look carefully at the edges that you become aware of the many layers of glazes that make up the picture surface. The painting begins to acquire depth and the longer you look at it, the more what you thought was blackness begins to rupture, and you see a warm, ruddy-brown tone. For me, this painting radiates an incredible feeling of calm and invites contemplation.

Aesthetics of Nature: Jewels of the Air

They exercise a magical power of attraction over me – the butterfly jewel cases! Butterflies! After short cold days and long nights, we long for their arrival on the first warm breeze. These apparently aimless, light-weight flutterers announce the arrival of spring and the approach of summer – early harbingers of the bright, warming time of year. In their many different shapes and sizes and their huge variety of colours – some with a metallic gleam, others with striking markings, some magnificent, some transparent, daylight dancers and flying nocturnal acrobats – they are all equally dear and precious to me. In their unique and multifaceted way, they all demonstrate nature’s urge to play. If we humans (equipped with three colour receptors) could see what butterflies see with their six receptors, then we would find the lepidopteran world even more colourful. Butterflies’ riot of colours is the result of pigments in tiny scales on their wings. March 14 is annual ‘Learn-More-About-Butterflies’ day in Germany. When Museum Wiesbaden is open, that’s the kind of day I have every time I visit. After beetles, the Lepidoptera include the greatest number of different species of any order of insect. I discovered that the name ‘butterfly’ has a tasty but unscientific origin. People used to believe that butterflies sucked milk, cream, and butter. Although they are so precious, we have lost a quarter of our insects in the space of a few decades. Yes, the butterfly is an insect too. The Anthropocene, the age of humankind, is leaving traces, and in this case, large holes. We are losing irreplaceable jewels. Looking at the butterfly cases, I can quietly forget that for a moment. Organized according to different criteria, such as patterning, coloration, and family relationships, the cases are luminous portraits of butterflies and moths. Did you know the green hairstreak has been declared ‘butterfly of the year’ 2020? As I contemplate the green hairstreak, my imagination takes flight. My memory travels to summer landscapes of the past. My thoughts and anticipations wander into next spring. It’s a good way of by-passing autumn and winter days; in the same way I can look forward to better times ahead. Today, one day before the reopening of the museum, it is particularly grey and eerily cold outside. For now, I can make do with looking at the exhibition catalogue ‘Aesthetics of Nature’. And tomorrow, at last … my ‘Jewels of the Air’! If jewels were alive, they would wish to be butterfly wings. ‘It’s a kind of magic …’

Translated by Lance Anderson