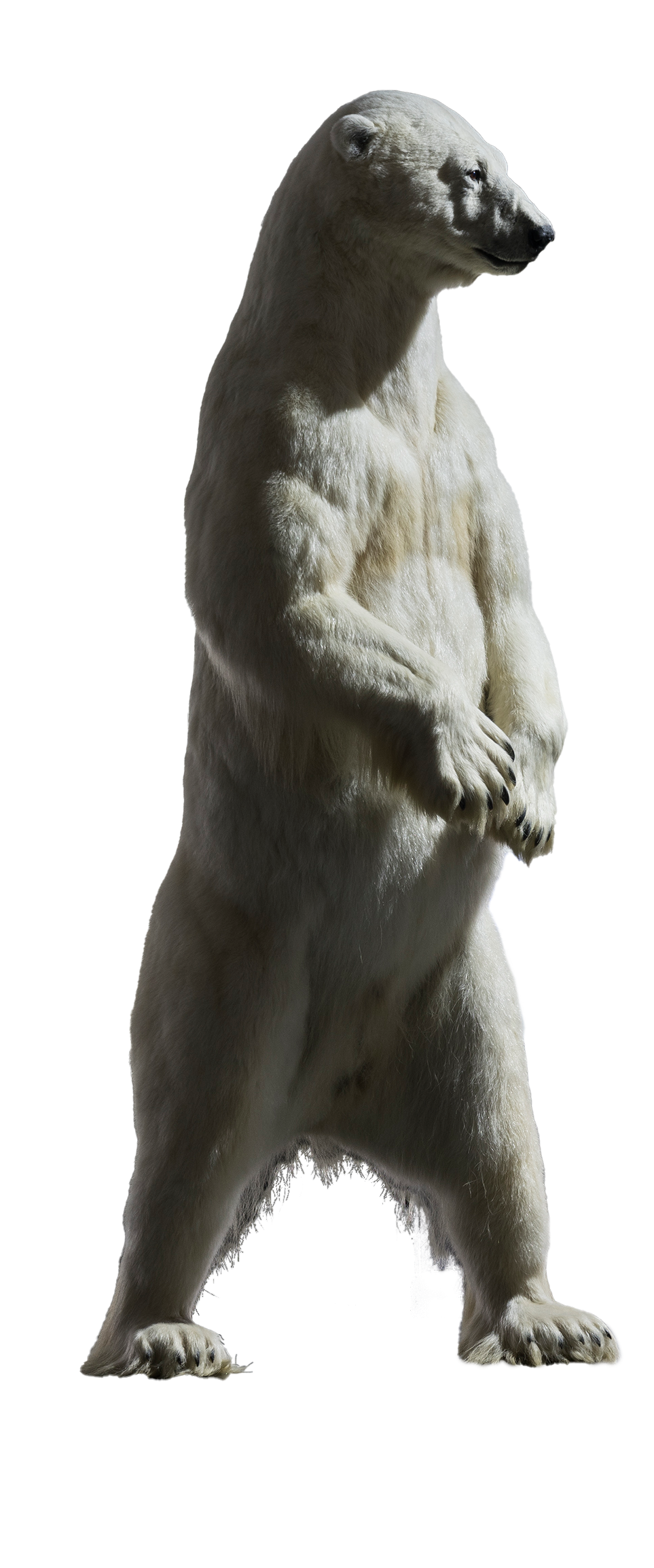

The colours and patterns of the natural world surprise, enthuse and amaze us. The extravagant plumage of the male peacock, the purposeful whiteness of the polar bear’s fur, the tree bark pattern of a butterfly’s wing, or eyes inspiring fear — these are all the result of evolutionary development. Over a thousand butterflies, hundreds of birds and plentiful specimens of mammals and plants provide visitors a fascinating look at the seemingly infinite strategies and rules of camouflage and concealment, attraction, and repulsion in the natural world. From radiant color to masterful camouflage, the exhibit answers our questions about the phenomenon of color. How does the red get into the feathers? Why can’t predators see it? What makes the hummingbird’s wings iridescent? Why is the marmoset’s fur so shiny? The “Colour” display invites visitors to discover the colours of nature anew. Here animals, plants and minerals are exhibited according to colour. Some animals are so well camouflaged in the dense green of the rain forest or the airy deciduous forest, you will have to searched for them first.

Every animal group perceives its environment in a unique way. While humans have scientific evidence of other colour worlds, we cannot always comprehend them. Colourants also serve other functions that are essential for survival. Why red animals are well camouflaged in the sea or how parakeets get their yellow colouring are just two of many selected color phenomena presented in the colour octagon. Nature's colours have inspired the artistic and creative energies of humankind to search for the appropriate materials and means of reproducing and employing them in all nuances. The colourants in the colour octagon complete the exhibition on the colours of nature and the nature of colour.

There is evidence that man has been using colours for 55,000 years. Nature provides the necessary raw materials: Earth pigments in all shades and minerals, such as the yellow auripigment, green malachite, or lapis lazuli for one of the most intense blues possible. Dyes such as indigo or cochineal are obtained from plants and animals. The first synthetic pigment, Egyptian blue, was developed by the Egyptians around 2500 BC. An eight-section showcase featuring 120 pigments and dyes traces the cultural history of colorants. There are sections reserved for the colours that the human eye perceives as pure colour, i.e., red, yellow, blue and green, as well as for the achromatic colours black and white. Other sections are reserved for earth tones and color effects, such as the iridescence of hummingbirds and mother-of-pearl shells. The pigment or dye is exhibited as the painter or dyer would have it before mixing the paint or vat. Also on display are the sources of non-synthetic colorants, such as historic piuri, the commercial form of Indian yellow, which has not been produced since 1914. Only on the surface do the colors unfold their effect.

Museum Wiesbaden offers a variety of programs for all ages, from guided tours to workshops for preschools and schools, to teacher training and programs for students, private groups, or families with children.