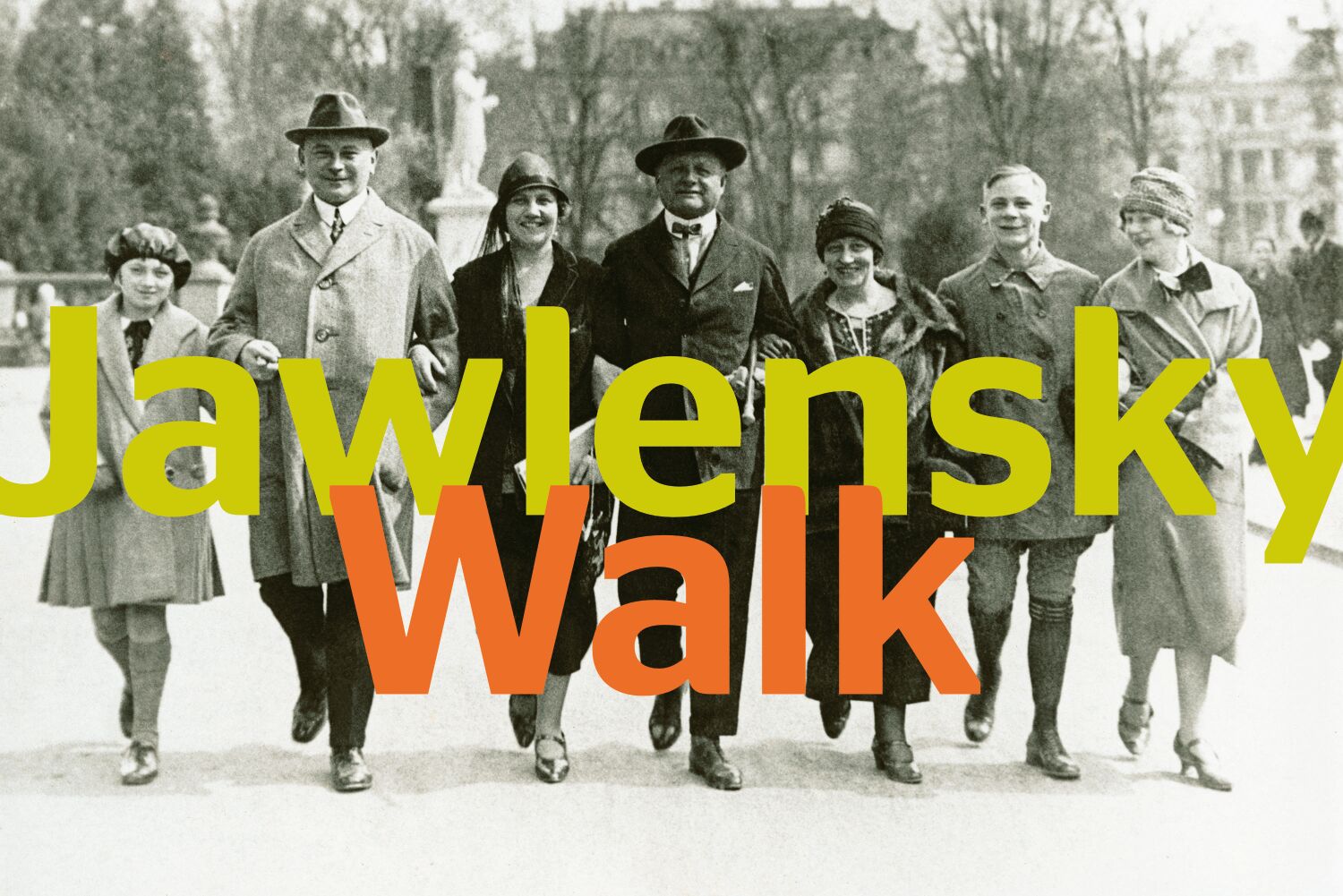

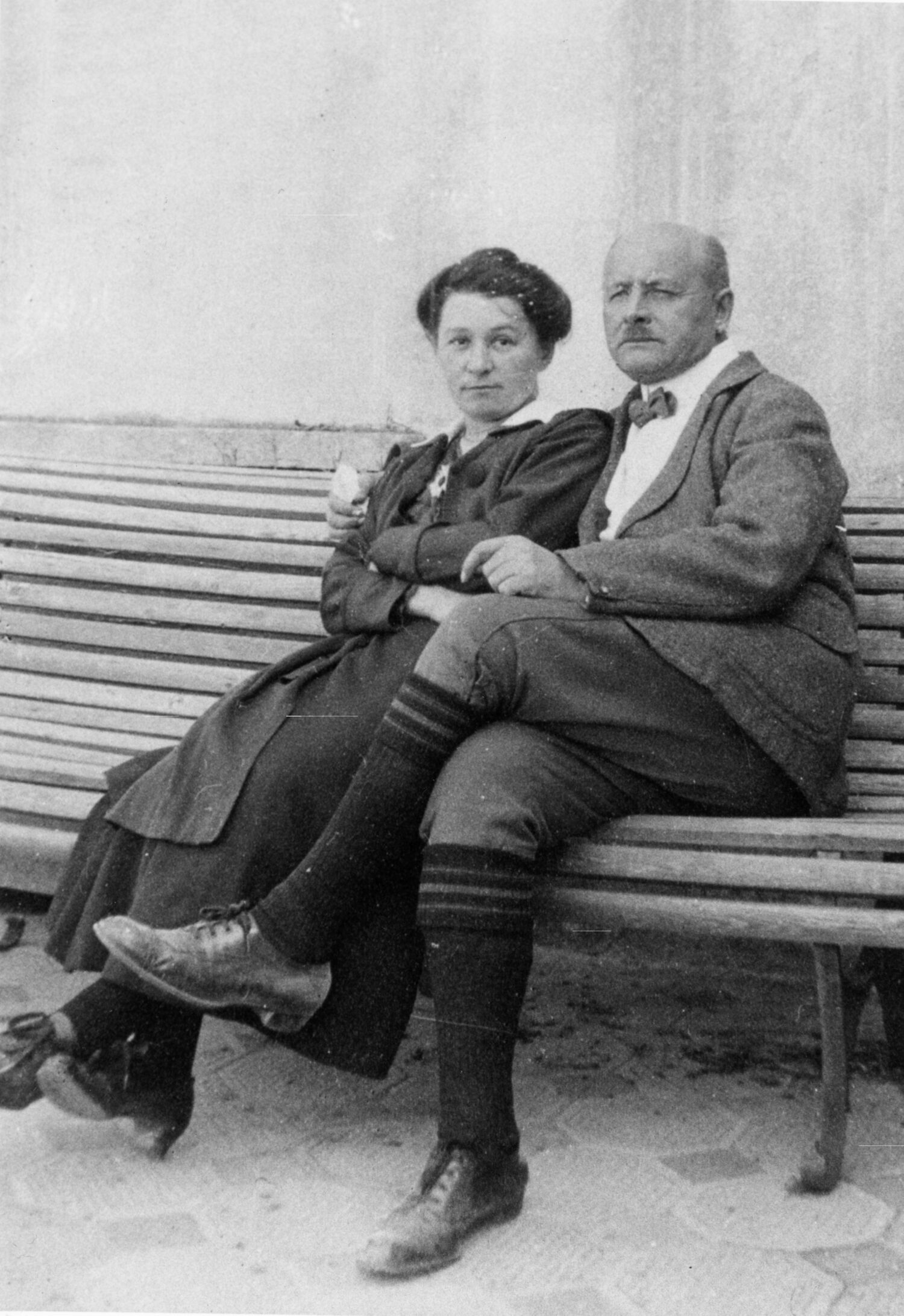

Alexej von Jawlensky among his friends at Warmer Damm, Wiesbaden 1924. Photo: Private Archive Kirchhoff, Estate Mieze Binsack

‘They’re already expecting me in Wiesbaden’ wrote Alexej Jawlensky to a friend in Zurich on 31 May 1921.

A tour across Wiesbaden

Route

Follow Jawlensky's footsteps and discover stories and historic places within the city of Wiesbaden related to the artist.

At the Wiesbaden Tourist Information and at Museum Wiesbaden you can get a folding map showing you the stations on your way through the city.

Open the map here.

Station 1

Wiesbaden Main Station1. June 1921 – Jawlensky arrives:

'They’re already expecting me in Wiesbaden,’ wrote Alexej Jawlensky to a friend in Zurich on 31 May 1921. The painter was sitting at the Badischer Bahnhof in Basel, waiting for the night train to Wiesbaden. The success of his exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden that spring had put the city on his map. The next day he arrived at the main station and received such a warm welcome that he soon decided to settle down there for good. The famous Expressionist painter, who had been a member of the artist group Der Blaue Reiter, would live at Nikolasstrasse 3 (today Bahnhofstrasse 25) until 1928. He then moved to Beethovenstrasse 9, becoming a neighbour of his patron Heinrich Kirchhoff. The local museum, today home to the most significant Jawlensky collection in the world, frequently exhibited the painter’s work during his lifetime. Jawlensky quickly felt at home in Wiesbaden—in part thanks to the large Russian Orthodox community, which has been here since the first half of the 19th century.

Adress:

Hauptbahnhof Wiesbaden

65189 Wiesbaden

Station 2

The museum, the city, and the artist

The fact that Museum Wiesbaden today has one of the most comprehensive collections of Alexej von Jawlensky’s art is not only due to the artist having lived here for the last 20 years of his life. It is, above all, the merit of Wiesbaden residents who, for years, dedicated their lives in numerous ways to art and promoted Jawlensky’s artistic work throughout his life and after his death – making Museum Wiesbaden, by and large, the pivotal point of their activity. Today, Jawlensky is the namesake of a school, a bus stop, a street, and, finally, an art prize that extends his reach far beyond the museum itself. His fresh start in Wiesbaden, his new home, his circles, and the stories of his companions are told, now, through the museum’s extensive Jawlensky collection and can be experienced at the original locations on the Jawlensky Trail. You can start your Jawlensky discovery tour right here at Museum Wiesbaden!

Adress:

Museum Wiesbaden

Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 2

65185 Wiesbaden

Station 3

Helene steps in! Susanne’s Beauty Institute

In the late 1920s Jawlensky’s painting sales notably declined. On the one hand, this was due to the world economic crisis, which had severely impacted even wealthy patrons like Heinrich Kirchhoff. But it was also the effect of the emergent new cultural policies of the Nazis. To ease the family’s financial difficulties, Helene von Jawlensky trained as a make-up artist in Paris, and in the summer of 1928 opened ‘Susanne’s Beauty Institute’ diagonally across from the Museum Wiesbaden. On 15 January 1929 Jawlensky wrote to Erich Scheyer, the brother of Galka Scheyer, who represented the artist in the United States: ‘Helene works diligently in her salon, to great success.’ But on 17 February 1932, he told Galka that ‘Helene no longer has her institute.’ The beauty salon thus lasted just under four years. It is possible that she stopped working to tend to Jawlensky, who had become visibly sicker and required daily care.

Adress:

Wilhelmstraße 2–4

65185 Wiesbaden

Station 4

A traveling exhibition, the Nassau Art Association, and “Jawlensky mania”

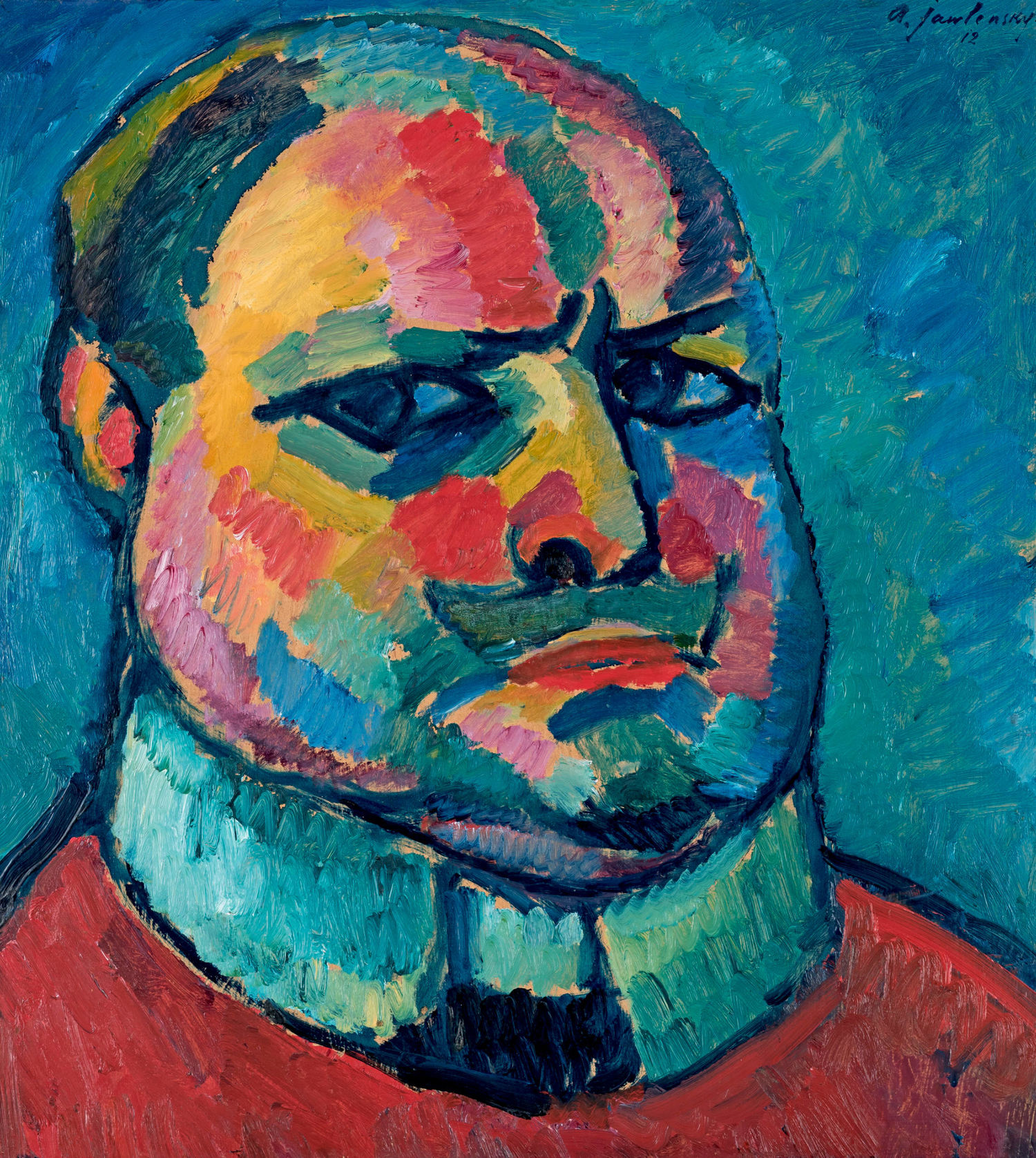

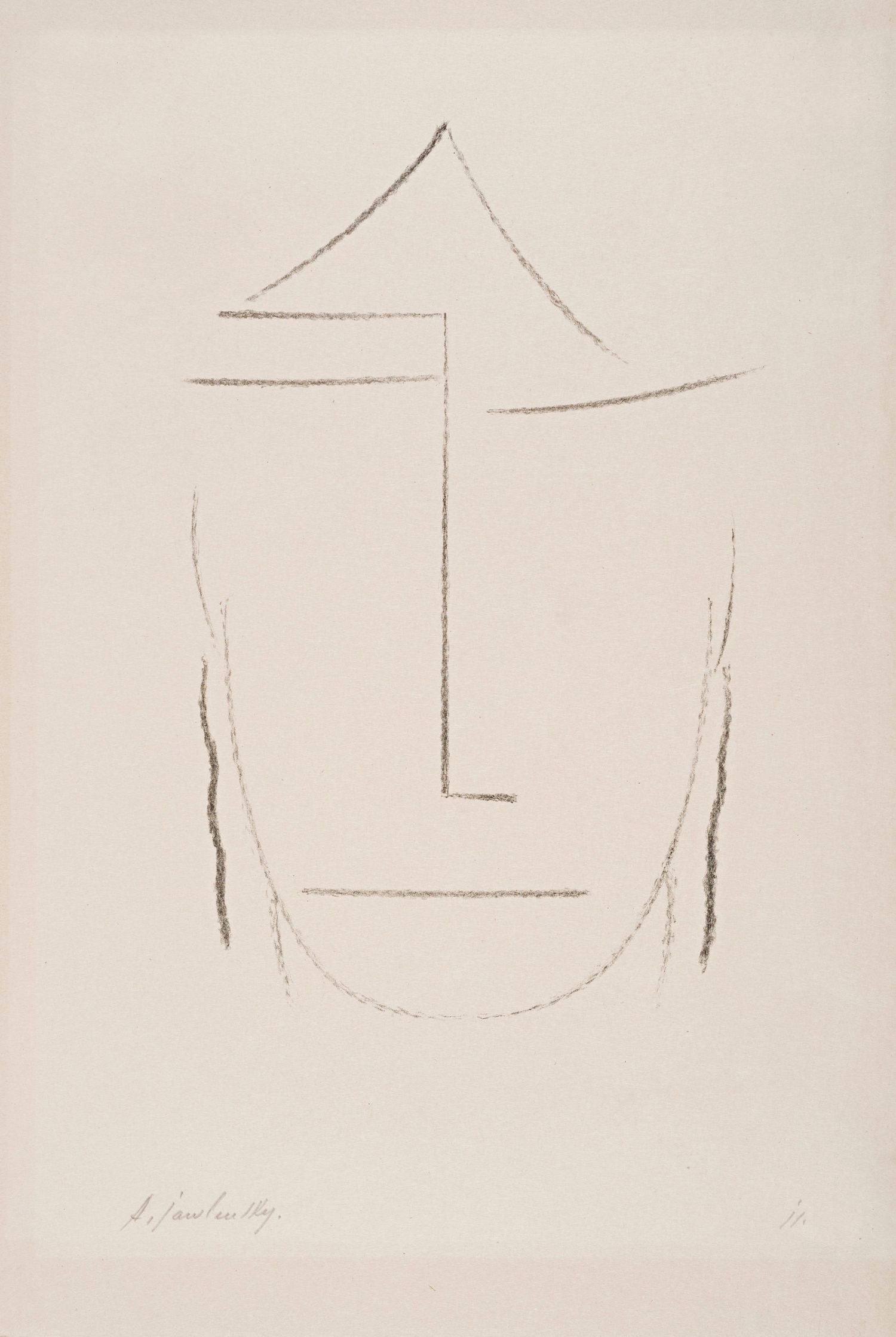

After shows in Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, Hanover, and Frankfurt, Wiesbaden 1921 is the sixth stop of Jawlensky’s traveling exhibition – and it is by far the most successful. The organizer of this Wiesbaden exhibition at the New Museum Wiesbaden was the Nassauische Kunstverein [Nassau Art Association]. Strictly speaking, it was through the Association that “Jawlensky mania” was awakened, as Galka Scheyer, the artist’s agent, later acknowledged to the city. The rest is history: Jawlensky decided to take a closer look at the city where he had had such success. He met Heinrich Kirchhoff, a patron of the arts who would become so important to him, and with the support of the Association, they found an apartment for the artist and his family in 1922, located at what is now Bahnhofstraße 25. That same year, the Association published Jawlensky’s graphic portfolio Köpfe[Heads], whose six prints form the beginning of this year’s exhibition. Today, these works are an early testimony of the evolution towards Jawlensky’s Abstrakten Köpfen [Abstract Heads], which were to have a major impact on his art in Wiesbaden.

Adress:

Nassauischer Kunstverein

Wilhelmstraße 15

65185 Wiesbaden

Station 5

Die zweite Wohnung Jawlenskys in Wiesbaden

Alexej von Jawlensky moved to Beethovenstraße with his wife Helene and son Andreas on May 1, 1928, where he lived until his death on March 15, 1941. The proximity to his patron, the art collector and garden enthusiast Heinrich Kirchhoff (1874–1934), was probably a decisive factor in the move. He lived in an urban villa in the immediate vicinity. Jawlensky became an integral part of the Kirchhoff family, who were only too happy to invite him to their family celebrations. By the time of the collector's death, over 100 works by Jawlensky had been added to Kirchhoff's collection. The works stored in the cellar of Jawlensky's home survived the Allied bombing on February 2, 1945, largely thanks to the efforts of Helene von Jawlensky. Käthe Henkell, the wife of the founder of the sparkling wine producer Otto Henkell, who died in 1929, also lived in Beethovenstrasse and sent the gardener with a wheelbarrow to collect the paintings.

Adress:

Beethovenstraße 9

65189 Wiesbaden

Station 6

To see and be seen: Strolling in Warmer Damm park

Nestled between old town, the state theatre, and museum mile, Warmer Damm park has provided people with a place to relax in the middle of the city for over 160 years. Laid out in the style of an English garden, it was and continues to be an ideal location for a casual stroll—an activity that Alexej von Jawlensky, too, enjoyed. This photograph, in which the Schiller monument can be seen just left of centre, was taken in the mid-1920s. It shows Jawlensky, sauntering alongside his friends, the Kirchhoffs and the Reuters. Their joyful expressions suggest an exuberant mood. Jawlensky, standing in the middle with linked arms, appears to have fully arrived in the spa town.

Adress:

Warmer Damm Park

Paulinenstraße 15

65189 Wiesbaden

Station 7

United at last

After numerous stations in his life—from Russia, to Munich, to Switzerland—Alexej von Jawlensky made his home here in Wiesbaden for the last 20 years of his life. The extraordinary success of his art in 1921 at the „Nassauischer Kunstverein“ and the local Russian Orthodox community had a significant influence on this decision, and he was not to regret it. Here, he found trusted friends in the cultural scene who supported him intellectually and financially even in the most difficult times of illness and political censorship. Privately, too, though, all that belongs together finally came together here on the “Dern’sche Gelände” in front of the Wiesbaden registry office with his marriage to his partner of many years and mother of his son, Helene Nesnakomoff. Both found their final resting place in the Russian Cemetery on Neroberg, though many other places throughout the city tell the story of the Russian Expressionist and his family in Wiesbaden

Adress:

Standesamt Wiesbaden

Marktstraße 16

65183 Wiesbaden

Station 8

Helene Jawlensky alone in Wiesbaden

After relocating to Wiesbaden in 1922, the Jawlensky family—Alexej, Helene, and Andreas—quickly became integrated into Wiesbaden city life. Alexej von Jawlensky was sponsored by well-known Wiesbaden collectors and financially supported by a friends’ association founded in his honour. Helene Jawlensky briefly ran a beauty salon in Rheinstrasse, before fully devoting herself to her husband’s care. For a time their son Andreas, an artist himself, also worked as a tea, coffee and cigar merchant. But by the war’s end in 1945, Jawlensky’s widow Helene, daughter-in-law Maria, and grandchild Lucia were left destitute in Wiesbaden, with no permanent address, clothing, or financial resources to speak of. A bomb had destroyed their flat at Beethovenstrasse 9. Like so many others in their situation, they first moved into an improvised shelter. Here at Taunusstrasse 14 the family found their first home after the war. They remained until September 1953, when they moved only a short distance away, to Taunusstrasse 28. It was there that they were at last able to once again embrace Andreas—son, husband, and father, respectively—who returned to Wiesbaden in 1955, after spending ten years in Siberia as a prisoner of war.

Adress:

Jawlenskystraße

65183 Wiesbaden

Station 9

Neroberg: The grave of Alexej and Helene von Jawlensky

Alexej von Jawlensky died in his Wiesbaden flat at Beethovenstrass 9 on 15 March 1941. He was buried three days later in the Russian Orthodox cemetery on the hilltop known as Neroberg: ‘a gorgeous corner of the world, ’ as Lisa Kümmel wrote to a friend of Jawlensky’s after the funeral. His lifelong companion Adolf Erbslöh gave the eulogy. Jawlensky had visited Erbslöh at his home in Munich in 1937; it was his last major trip. Together they went to the exhibition ‘Degenerate Art’, which the Nazis had designed as a public attack on the avant-garde. Jawlensky was represented in the exhibition by two paintings and several works on paper; it was the low point of his career. A thoroughly apolitical painter, he felt defenceless and deeply misunderstood. This ‘dark’ turn in cultural policy that oppressed Jawlensky enormously during the last years of his life appeared to lift on the day of his death: like the day of his funeral, it brought ‘wonderful spring weather’. His wife Helene died on 17 March 1965 in Locarno and, at her arrangement, was buried beside Jawlensky.

Adress:

Russisch-Orthodoxe Kirche der hl. Elisabeth

Christian-Spielmann-Weg 2

65193 Wiesbaden

Published by

This website uses cookies. By visiting the site you agree to this. More information.