Alphonse Mucha, bust, Nature (La Nature), detail view, c. 1899. Museum Wiesbaden, Ferdinand Wolfgang Neess Collection. Photo: Museum Wiesbaden / Bernd Fickert

Discover the rich architectural heritage of Art Nouveau buildings in Hesse's state capital

— from magnificent residential buildings to cemeteries, from art collections to thermal baths.

Route

On the trail of Art Nouveau

At the Wiesbaden Tourist Information and at Museum Wiesbaden you can pick up a folding map showing you the stops on your way through the city.

Open the map here.

Off the path

Discover Wiesbaden's Art Nouveau buildings using the Geoportal der Stadt Wiesbaden. On your way through the city's residential neighbourhoods, you can spot numerous Art Nouveau treasures.

Stop 1

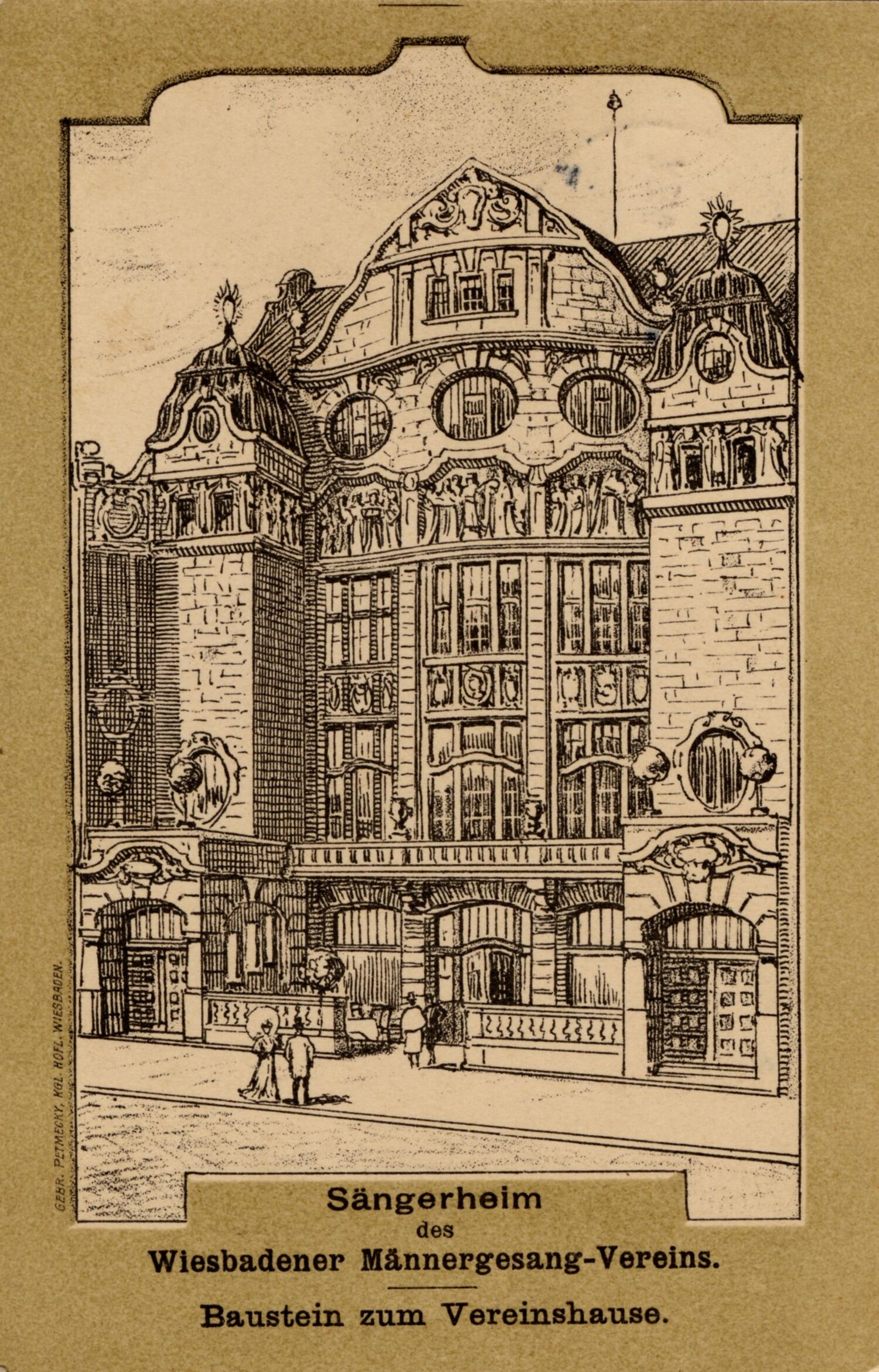

Wartburg

The Wartburg is located on the edge of the city centre, not far from Platz der Deutschen Einheit. Built in 1906, the building is now used as one of the venues of the Hessian State Theatre in Wiesbaden. The Wartburg was commissioned by the Wiesbaden Male Choral Society. This is also evident in the curved, light-coloured sandstone façade with its reliefs. The Wartburg Castle near Eisenach, the setting of the Tannhäuser legend and the subject of Richard Wagner's romantic opera, inspired the builders to choose this name. The five-panel relief frieze above the second floor also refers to the legend. It depicts the protagonists of the famous Minnesänger's Contest described in a collection of Middle High German poems from the 13th century. It bears witness to the period when literature flourished at the Wartburg court and to Thuringian poetry. In 1876, the Choral Society commissioned Höppli, a company based in Wiesbaden (Wörthstraße 4–6, architect: Georg Friedrich Fürstchen) to produce the frieze.

Address:

Schwalbacher Straße 51

65183 Wiesbaden

Stop 2

Pressehaus

Anyone who spends time in Wiesbaden's city centre will at some point have walked past the impressive building where the Wiesbadener Kurier, a regional daily newspaper, is headquartered. The press building on Langgasse is a true Art Nouveau ‘newspaper palace’. It was built between 1905 and 1909 on the site of the Schellenberg'sche Hofdruckerei printing press, from which the local newspaper, Wiesbadener Tagblatt, emerged. For the central risalit of the building, tThe architects Lang, Wolff & Hertel chose a red sandstone façade with an aesthetically appealing beige veining that creates a colour connection to the three-storey sections of the building to the left and to the right. The façade combines late historicist details with Art Nouveau elements in an impressive manner. Above the central gable, a male figure raises a book, thus, in a figurative sense, pointing out the value of enlightenment. The copper statue, created by Philipp Modrow, corresponds to the two bronze eagles by Carl Wilhelm Bierbrauer, both sculptors from Wiesbaden. The eagles still hold the Wiesbaden city coat of arms in their claws. The lettering ‘Tagblatt’ on the cartouche above the first floor has since been replaced by the gold-plated letters ‘WK’ (for ‘Wiesbadener Kurier’).

Address:

Langgasse 21

65183 Wiesbaden

Stop 3

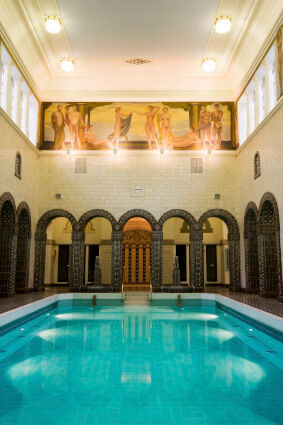

Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme spa

Wiesbaden is famous for its hot springs and bathing tradition. At the turn of the century, guests from all over the world celebrated today's state capital of Hesse as a world spa town. The Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme spa is considered a landmark of Art Nouveau in Wiesbaden. The first municipal public bathhouse in Wiesbaden was opened by Emperor Wilhelm II in 1913, the year marking his 25th anniversary on the throne. However, the neoclassical main façade only reveals this at second glance, namely through nine figurative Art Nouveau relief panels created by the Wiesbaden sculptor Wilhelm von Heider. Presumably in the Emperor's honour, the entrance hall was decorated with majolica tiles from the imperial manufacture in Cadinen (today: Kadyny, Poland) in the style of the 15th century Florentine workshop of the Della Robbia. Most of the interior was designed and executed by the Wiesbaden painter Hans Völcker, including the frieze in the entrance hall. It depicts the uncovering of the Wiesbaden springs and the development of local bathing culture from the time of the Mattiaci and Romans to the life reform movement around 1900. In his work, Völcker summarises the healing promise of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Therme spa in a painterly manner: the ‘path to strength, health and joie de vivre’ at any age. Admission to the entrance hall is free of charge. The interior of the baths is impressive in its Art Nouveau combination of beauty and practicality. Josef Vinecký, a colleague of Henry van de Velde in Weimar, designed the ceramic cladding and fountains in the hot air rooms. The ceramics in the swimming hall come from manufacturers in Darmstadt (Jakob Julius Scharvogel designed the brownish tiles) and Karlsruhe (Karl Huber created the two cream-white gargoyles, which were also used in the Sprudelhof in Bad Nauheim, a small town in Hesse). The Arcadian scene by Wiesbaden painter Ernst Wolff-Malm above the central cold water pool suggests that bathers are in the best of company.

Address:

Langgasse 38–40

65183 Wiesbaden

Stop 4

Palast Hotel

Not far from Wiesbaden's Kochbrunnen fountain and diagonally opposite the Hessian State Chancellery is the former Palast-Hotel. The magnificent façade of the grand hotel, which opened in 1905, faces Kranzplatz and Kochbrunnenplatz. The grand hotel was the premier address for the high society of the time, with the world-famous tenor Enrico Caruso (1873–1921) among its prominent guests. Legend has it that the singer used to rehearse with the windows open during his European tour in 1908, thrilling passers-by. The architectural appearance of the impressive building was shaped by three architects: Paul Jacobi planned and supervised the new construction; Fritz Hatzmann took over his duties in April 1904 until completion; and Theobald Schöll designed the six-storey Art Nouveau façade with its convex curve towards Kranzplatz and two lateral risalits. Architect Arthur Thürmer was in charge of the interior design. While the interior of the former hotel has changed significantly – today it houses residential units and shops –, the decorative glass dome of the former winter garden still bears witness to coffee parties and matinées with illustrious spa guests.

Address:

Kranzplatz 5–6

65183 Wiesbaden

Stop 5

Drei – Lilien – Quelle

Some of Wiesbaden's 26 thermal springs are accessible to the public as fountains, or are integrated into municipal baths and thermal spas, such as the Aukammtal thermal bath. However, thanks to the city's rich spa tradition, most of the large hotels also have private access to springs. One of Wiesbaden's most famous springs is located at the back of the Schwarzer Bock hotel. With its contrasting yellow and blue tiles, the spring is a gem of Art Nouveau. Anyone wishing to enter the room can do so by ringing a bell. The fountain chamber has a more austere Art Nouveau style and is one of the few places designed entirely in this style. Both the name and the colour scheme of the tiles are reminiscent of the coat of arms of the city of Wiesbaden. Its thermal water has connected the bathhouses of the city's renowned spa hotels since 1905. The Drei-Lilien-Quelle was threatened with decay for many years. In 2011, initiatives were launched to preserve the monument and thanks to extensive renovation, the fountain house now shines in new splendour.

Address:

An der Drei-Lilien-Quelle

65183 Wiesbaden

Stop 6

Muschelsaal (Shell Hall)

The route leads back across the forecourt of the Nassauer Hof hotel to Wilhelmstraße and the Bowling Green where the new Kurhaus, built in 1907 to designs by Friedrich von Thiersch, is located between the fountain colonnades and the theatre colonnades. The Kurhaus, which is one of Wiesbaden's landmarks, is an example of the stylistic pluralism of the time around 1900. Just behind the main entrance to the Kurpark, on the south side of the building, is the Muschelsaal, or Shell Hall, a former ‘garden hall’ with numerous Art Nouveau details. The spandrel fields of the vaulted ceiling feature stylised scallop shells made of stucco, while real nautilus shells, cone shells and mussels were used for the column capitals. Fritz Erler, a German painter, was commissioned to create the extensive frescoes for the rounded upper wall panels, depicting the four seasons and, above them, a fresco showing the stages of life. The Shell Hall can only be visited by permission of the Kurhaus, however, you may catch a glimpse through the windows from outside.

Address:

Kurhaus

Kurhausplatz 1

65189 Wiesbaden

Stop 7

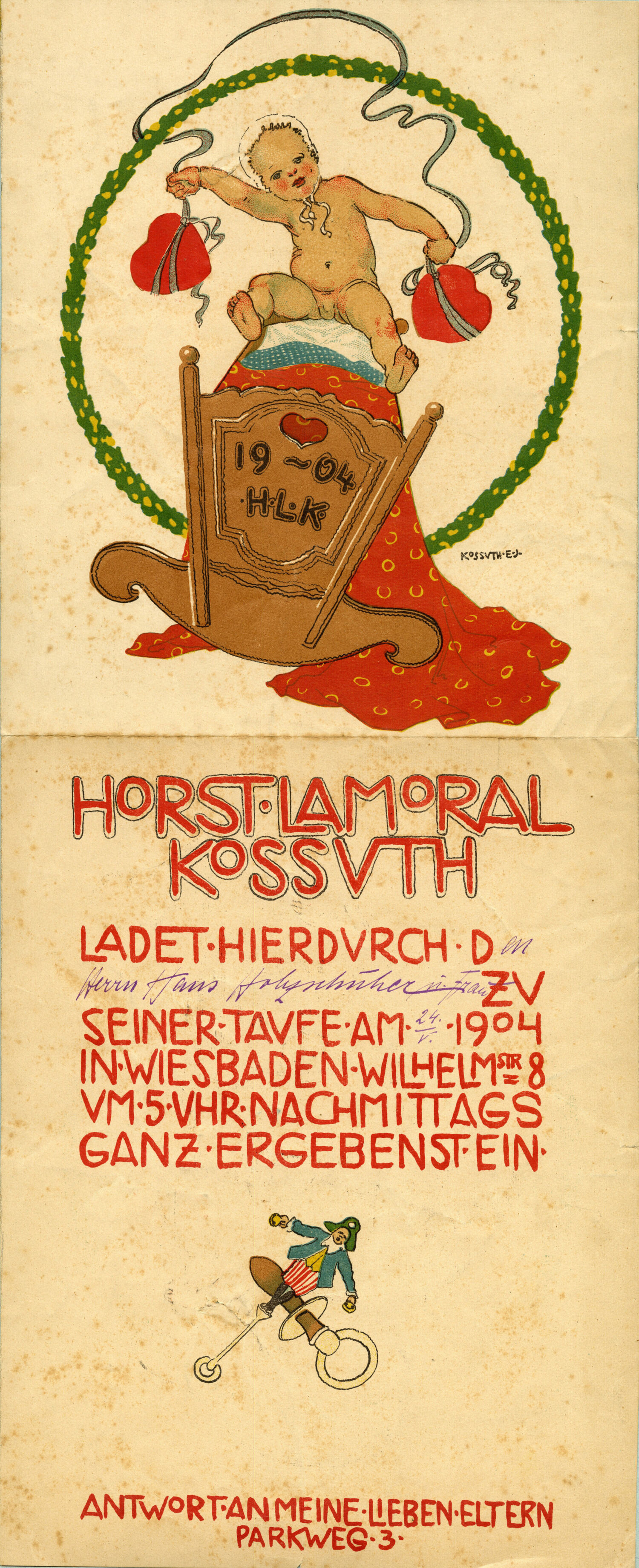

sam – Stadtmuseum am Markt city museum

Located in the historical market cellar, the museum offers an overview of Wiesbaden's city and regional history with a special focus on Art Nouveau, among other things. As an expression of ideas championed by the Lebensreform, or life reform, movement, Art Nouveau continued to characterise the cityscape and society until the early 1930s – in some instances from the cradle to the grave. The fact that nude figures were frequently depicted in nature reflected a new cult of youth and health. The city's advertising for air and sun bathing (Unter den Eichen) quoted the Light Prayer, an icon of the life reform and youth movement painted by Hugo Höppener, known as Fidus, and varied eleven times between 1890 and 1938. The motif became widely known in 1913 when it was published on a postcard. Life reform and Art Nouveau also had an impact on the design of the end of life: thanks to the commitment of the local Association for Popular Healthcare, the city of Wiesbaden obtained the right to cremation in 1912, and was able to eventually open the crematorium built in 1909 in the South Cemetery. The practice of cremation promoted the production of decorative urns created by artists. One such example is exhibited in the sam city museum. In addition, visitors can use a pattern generator to design their own Art Nouveau patterns and take them home with them.

Address:

Marktplatz 3

65183 Wiesbaden

Stop 8

F.W. Neess Art Nouveau Collection

Ferdinand Wolfgang and Danielle Neess' impressive Art Nouveau collection has been preserved at Museum Wiesbaden since 2019. The museum was built by architect Theodor Fischer, a co-founder of the German Werkbund. Fischer was a student of Friedrich von Thiersch (the architect of the new Kurhaus mentioned above) and teacher of Paul Bonatz, the architect of the Henkell sparkling wine cellars (1909, see below). He created three vestibules leading off from the octagonal entrance, which in turn led to the three museum collections, which were spatially separated at the time. When standing in the centre of the three-storey octagon, you can still spot their original names today (written on the round-arched grilles). Not least because of Max Unold's predominantly gold-coloured mosaic, the octagon is reminiscent of the Palatine Chapel of the Palace of Aachen. At the same time, the mosaic with its inlaid coats of arms and city silhouettes refers to places and landscapes as well as the professions of Wiesbaden's population. On the second floor of the octagon, in round niches below the dome, there are four statues by the Wiesbaden artist Arnold Hensler, which – like his female figures on the north and south façades at the level of the first floor – are reminiscent of his collaboration with Bernhard Hoetger on the sculptural design of the Plantanenhain, or Plane Tree Grove, on the Mathildenhöhe (an artists' colony on the top of a hill in Darmstadt). A fountain featuring Art Nouveau elelments is placed at the end of the three-aisled hall. While the entrance portico is modelled on ancient architecture, the fountain refers to Wiesbaden's Roman bathing tradition. The interior rooms were painted by Hans Völcker – which is still visible today in the collection area in the octagon to the left of the fountain. The fantastic Art Nouveau collection of Ferdinand and Danielle Neess welcomes you on the first floor. More than 500 objects form a cross-section of all genres of Art Nouveau. The spectacular collection comprises objects of applied art such as furniture and objects made of glass, porcelain and ceramics.

Address:

Museum Wiesbaden

Hessian State Museum of Art and Nature

Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 2

65185 Wiesbaden

Stop 9

Lutherkirche (Luther Church)

Another impressive Art Nouveau creation is the Lutherkirche, or Luther Church, built between 1908 and 1910 based on plans by Friedrich Pützer and inaugurated on 8 January 1911. The character of Luther Church as an Art Nouveau Gesamtkunstwerk is primarily expressed in its exquisite artistic decoration, which is the joint work of numerous artists. The brothers Rudolf (1874–1916) and Otto Linnemann (1876–1961), glass and decorative painters in Frankfurt am Main, conceived the expressive colour scheme of the interior, which was recreated between 1987 and 1992 based on the original findings, and the symbolic ornamentation covering the entire ribbed vault, a combination of stylised, botanical interlaced ornaments and flowers as well as exotic geometric patterns. They also designed the stained glass windows and an Art Nouveau fresco in the former bridal staircase, which is no longer accessible but still preserved in situ. Augusto Varnesi (1866–1941), sculptor and medallist and, like Pützer, professor at the Technical University of Darmstadt, created the magnificent vestibule with a mosaic barrel vault, tympanum, and golden mosaic walls. Such elaborate decoration was made possible thanks to a donation. He also designed the vestibule with the baptistery and, in collaboration with Pützer, the chancel and and retrochoir. The chandeliers, the altar cross, and the Bible stand are the work of goldsmith Ernst Riegel (1871–1939), a member of the Darmstadt artists' colony.

Address:

Sartoriusstraße 16

65187 Wiesbaden

Stop 10

'Etagenlandhaus' Art Nouveau villa

The Wiesbaden architect Friedrich Wilhelm Werz (1868–1953) also ''demonstrated his commitment to Art Nouveau when he built his well-preserved residence at Dambachtal 20 in 1901/02, which is still well preserved today. He enlisted the help of the renowned Art Nouveau artist Hans Christiansen, one of the first seven artists appointed to the Darmstadt artists' colony in 1899, to design the exterior and interior of the housebuilding. Christiansen was responsible for the design ofdesigning the wide broad frescoed floral frieze that runs around the villa below the roof, and extendings down to the first floor in the central risalit. He also created the templates for the decorative glazing of the staircase windows and apartment doors, of which only fragments remain. Other modern features include the curved mansard roof, the flat uniform wall treatment, the avoidance of historicistm in the ornamentation and, made possible bythanks to the numerous large number of balconies, the many references to the surrounding nature.

Address:

Dambachtal 20

65193 Wiesbaden

Stop 11

Weißes Haus (White House)

The so-called 'Weißes Haus', or 'White House', at Bingertstraße 10 was built by architect Josef Beitscher as his family residence in 1901/02. It is one of the first German examples of the struggle for a new style. The sculptural structure and the preserved parts of the enclosure are richly decorated with figurative and botanical, but also geometric Art Nouveau motifs. Inside the building, there are carved and stucco ceilings decorated with floral ornaments and depictions of angels. Beitscher, who, like Joseph Maria Olbrich, was a student of Karl von Hasenauer in Vienna, sought to combine architecture and decoration. He united architecture, sculpture, and painting in his villa, thus creating one of the first pure Art Nouveau houses in Germany. In the 1970s, this Art Nouveau treasure was not listed as a historic building and was therefore threatened with demolition. Thanks to the initiative of architect Friedhelm Gerecke, it was saved from this fate. Ferdinand Wolfgang Neess acquired the house in 1986 and had it extensively restored over a period of two years. The Neess couple not only collected Art Nouveau in the 'Weißes Haus' for decades, they also lived according to its principles. Today, the Neess Collection is preserved, and put on show, in the Museum Wiesbaden.

Adress:

Bingertstraße 10

65191 Wiesbaden

Stop 12

Mourning Hall

One of the most accomplished examples of late Art Nouveau interior design is the mourning hall at the Südfriedhof, or South Cemetery, completed in November 1911. Its magnificent decoration was the work of several artists. The sculptor Carl Wilhelm Bierbrauer created two supraporte panels and a frieze depicting a funeral procession in the northern portico. Inside the three-aisled mourning hall with its square centre and crowning dome, the sculptors Ernest (1879–1916) and William Ohly (1883–1955), two German-English brothers who ran their studio in Frankfurt am Main, created the columns in rich relief in the niche behind the catafalque. Hans Völcker also worked on the interior, designing the wall paintings for the room and carrying out some of them himself. Above the reddish grey Nassau marble cladding of the walls, which extends to a height of around four metres, he created a frieze of figures on the west, north, and east sides, the subject of which is based on the inscription on the south gallery: ‘One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh / But the earth abideth for ever.’ In collaboration with his wife, Hanna Völcker, he also designed the lavish ornamentation of the walls above the frieze and the ornamental figurative painting of the dome. Numerous favourite Art Nouveau motifs such as peacocks, rose bushes, lilies, and a flower wreath reminiscent of Gustav Klimt in the dome are featured here.

Address:

Siegfriedring 25

65189 Wiesbaden

Stop 13

Art Nouveau tombs

Opened in 1877, Wiesbaden's Nordfriedhof, or North Cemetery, contains real treasures in the form of sculptural works and tombs from the early 20th century. The artistic craftsmanship reflects how Art Nouveau linked art and life even in death. A stroll through the cemetery invites visitors to discover sepulchral steles, sculptures, and chapels. Highlights include the historic grave of Fritz Baum (1851–1906), designed by Hans Dammann with a statue of a mourner, which can be found in variations in German cemeteries. The family grave of industrialist Heinrich Albert (1834–1908) was erected by sculptor Franz Metzner, based on a design by the Dresden architect Johannes Baader, with references to the Vienna Secession and figural stone reliefs. The sepulchral stele by sculptor Fritz Roth (1855–1905) and the Art Nouveau monument to Marie John (1848–1910) are characterised by rose decorations. Other noteworthy masterpieces include the grave sculpture for Christine Becker (1849–1907), depicting a mourning woman designed by Gustav Rutz, and the monuments created by Wiesbaden sculptor Carl Wilhelm Bierbrauer (1881–1962), a fountain with two water carriers, and the tomb of lawyer Heinz Brass (1887–1930), featuring a shepherd figure. They are examples of masterful local craftsmanship, as is Bierbrauer's own grave. Bierbrauer also created relief work on the façade of the Hessian State Museum in Wiesbaden while Metzner's works of art can be found in the museum's collection.

Address:

Hellkundweg 83

65193 Wiesbaden

Stop 14

Sektkellerei Schloss Henkell

The Henkell Trocken brand was influenced by the Art Nouveau movement. Otto Henkell, founder of the Henkell sparkling wine cellars, cemented the image of the famous sparkling wine during the height of Art Nouveau, and prominent artists – including painter Hans Christiansen (1866–1945) – contributed to the brand's visibility from 1894 onwards. He created three Tiffany-style stained glass windows for the production hall in Mainz – ‘Triumph of Wine’ –, which are now considered lost. For almost 20 years, renowned graphic designers such as Thomas Theodor Heine (1864–1948), Olaf Gulbransson (1873–1958), and Ernst Heilemann (1870–1936) created advertising designs for the brand that appeared in the relevant magazines of the era, ‘Jugend’ and ‘Simplicissimus’. The fact that some 200 advertisements designed by artists were published was something special for the Wilhelminian era. The interior design of the company building in Wiesbaden was also in the Art Nouveau style, from the offices to the atriums. This is documented in a special edition of the Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration magazine published in 1910. Today, the so-called ‘Blue Salon’, designed by Swiss painter and architect Hans Beat Wieland (1867–1954), has been preserved. A special highlight of the Art Nouveau room, which is decorated in English country house style, are the attractive blue paintings that tell the story of the creation of sparkling wine and its origins in wine. In addition, the company's own collection of labels, neck labels, and Art Nouveau typography bears witness to the splendour of Art Nouveau product design.

Address:

Biebricher Allee 142

65187 Wiesbaden

Published by

Imprint

Texts:

Stops 1–9, 11: Dr Vera Klewitz, Stadtmuseum am Markt city museum; Sina Hottenbacher, Wiesbaden Culture Office

Stops 9, 10, 12: Mechthild Maisant

Stops 13, 14: Susanne Hirschmann (based on Barbara Burckhardt's article „Schaumgeboren: Jugendstil für den Henkell Sekt“, 2019)

Editing: Susanne Hirschmann, Museum Wiesbaden

This website uses cookies. By visiting the site you agree to this. More information.