A new beginning with effects to the present day — the art of the 1950s and 1960s in Museum Wiesbaden. Art of the European and American Modern period after 1945 forms one of the museum’s most prominent collections, focusing on abstract painting and sculpture concerned with the themes of line, color, surface, volume, and space.

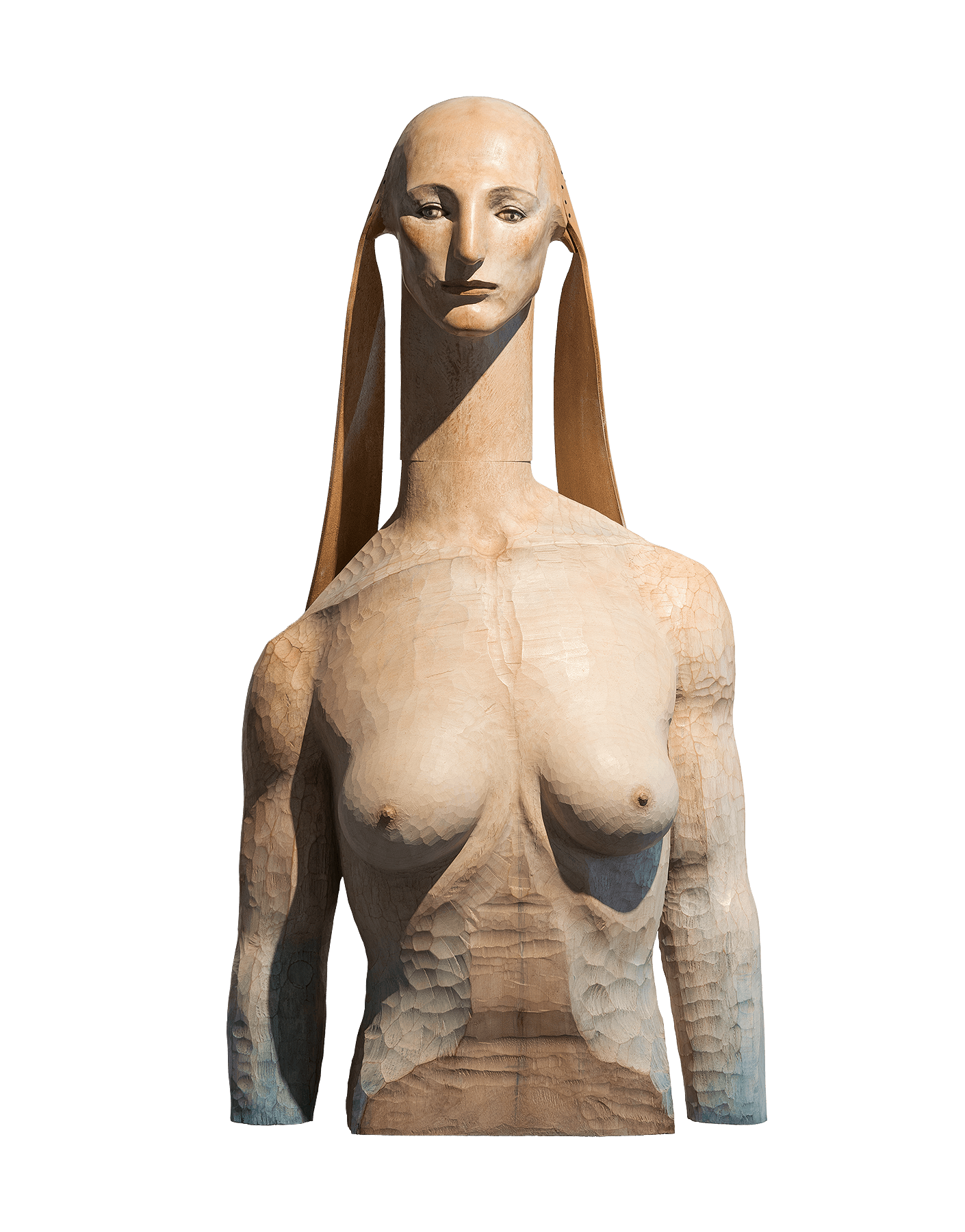

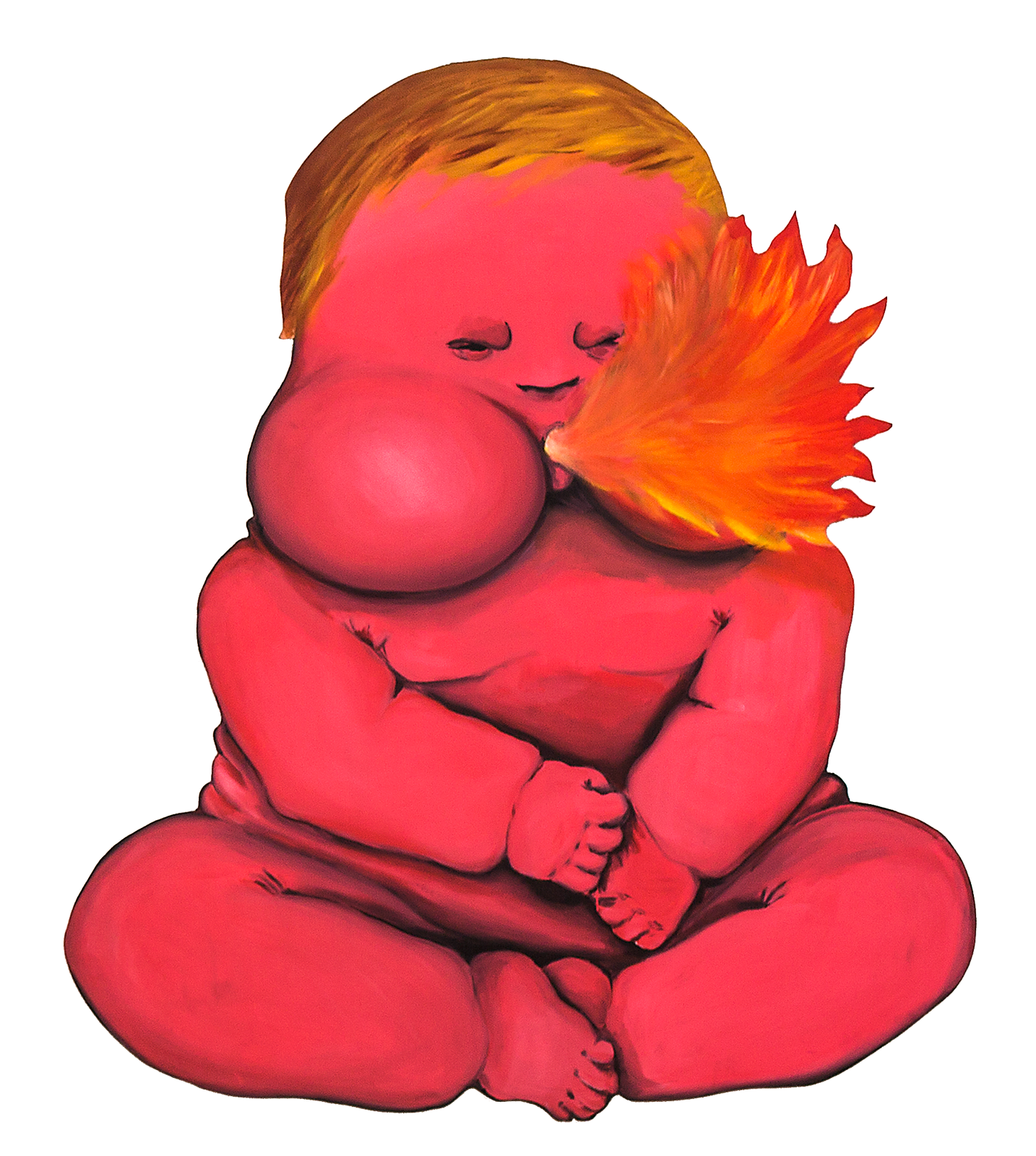

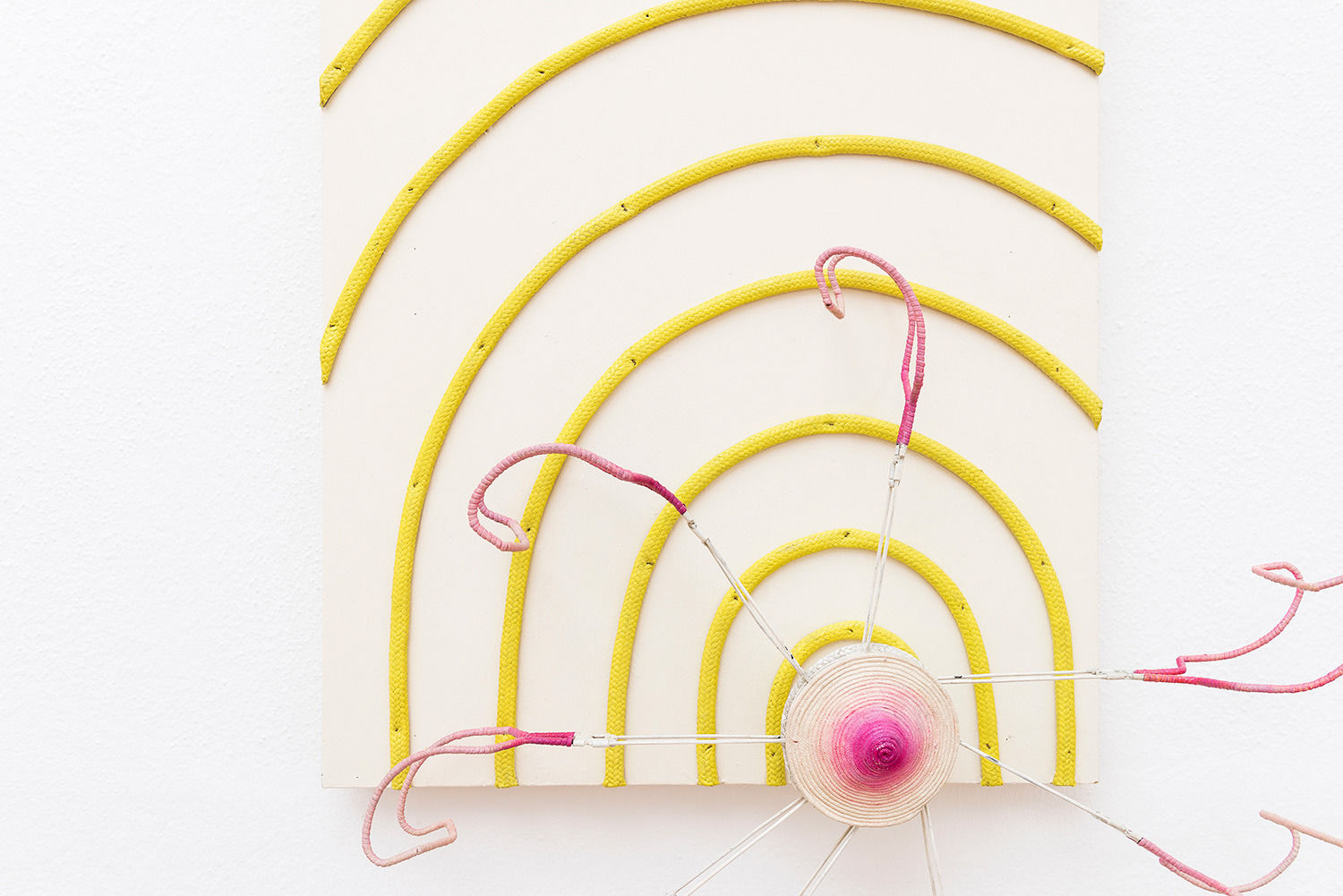

Contemporary art is shaped by conceptual installations, novel materials, and approaches, all of which is reflected in the collection of Museum Wiesbaden. These works confront us with questions about the nature of art, the conditions of its production, and the manifold levels of meaning they open up and to which they can be related.

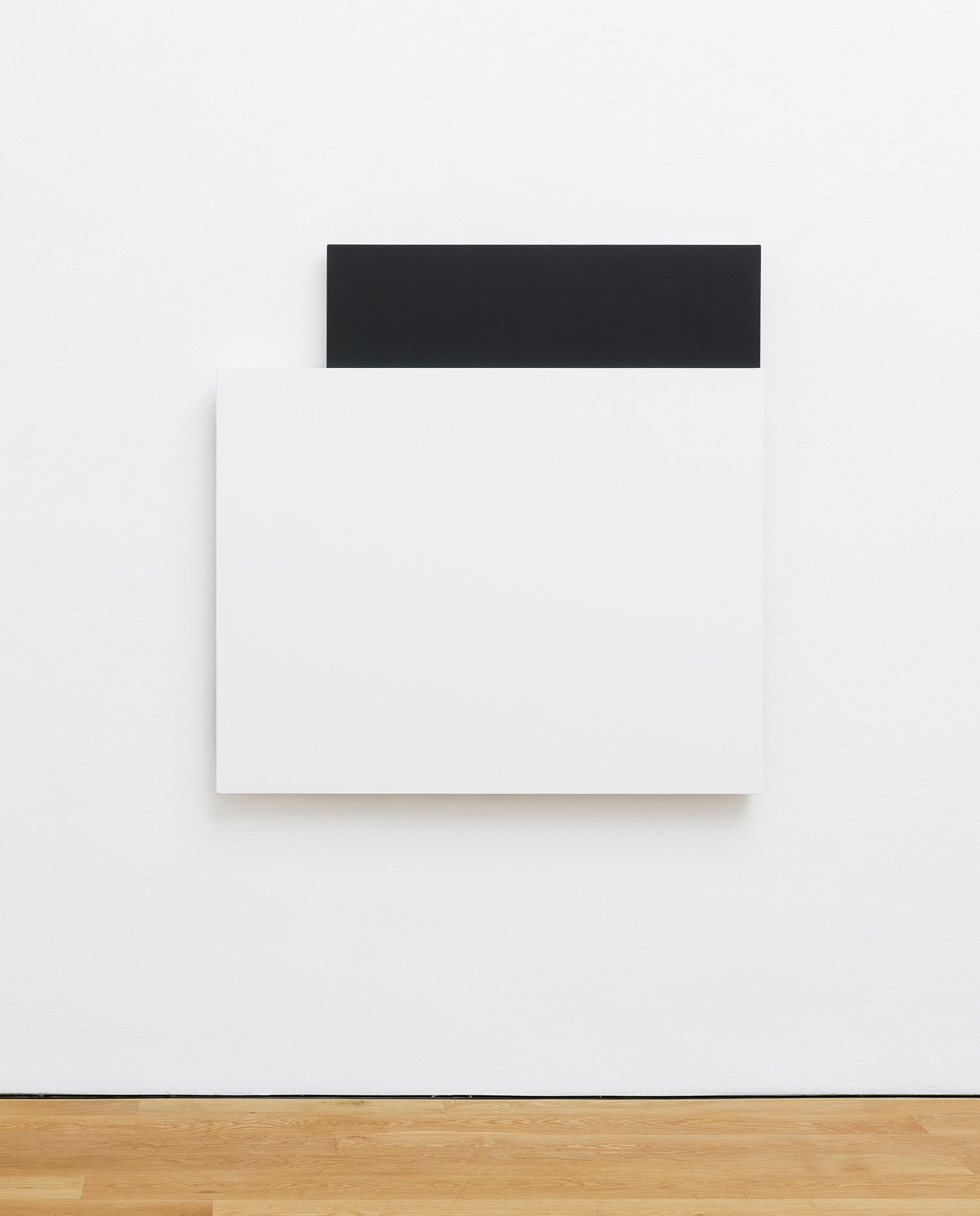

Installations by Jochen Gerz, Rebecca Horn and Ilya Kabakov, as well as works of American Minimal Art complete the collection. Entire work complexes are displayed in artist rooms, often in intimate rapport with the architectural features of the building itself. These mostly permanent presentations offer visitors constant points of departure and arrival as they wander through the museum. Yet, the would-be familiarity of our permanent exhibits is constantly questioned anew through their interplay with the museum's continually varying special exhibitions.

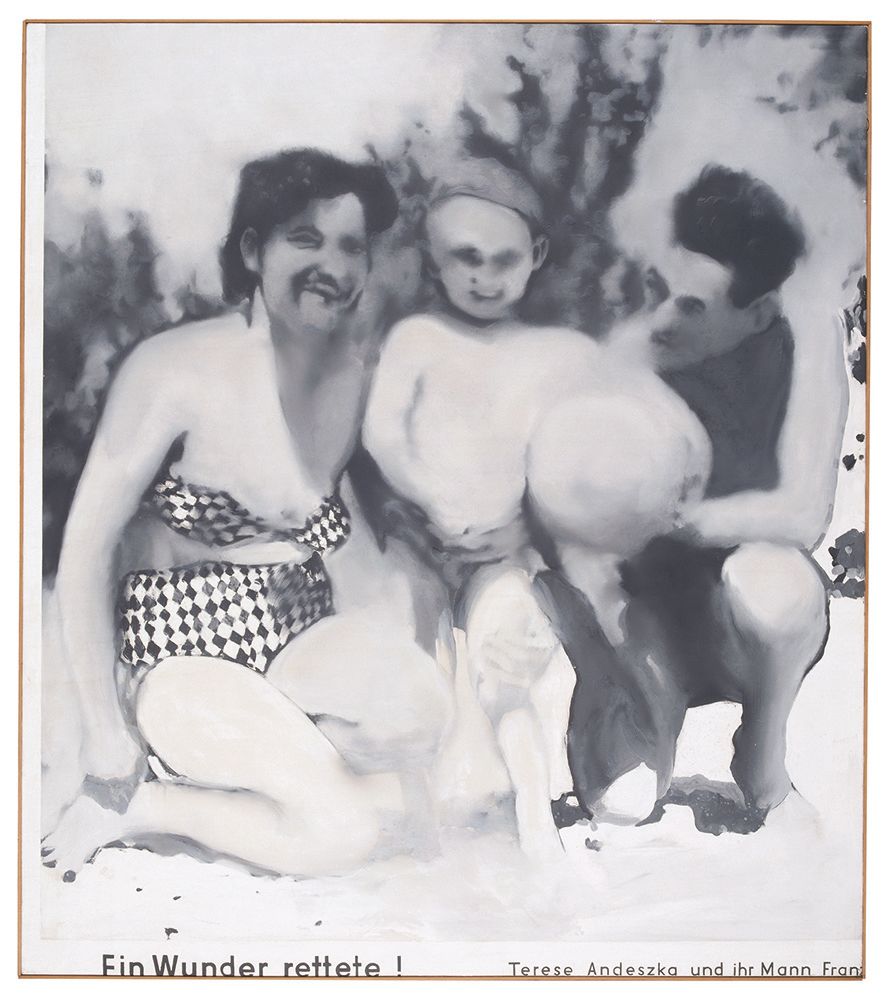

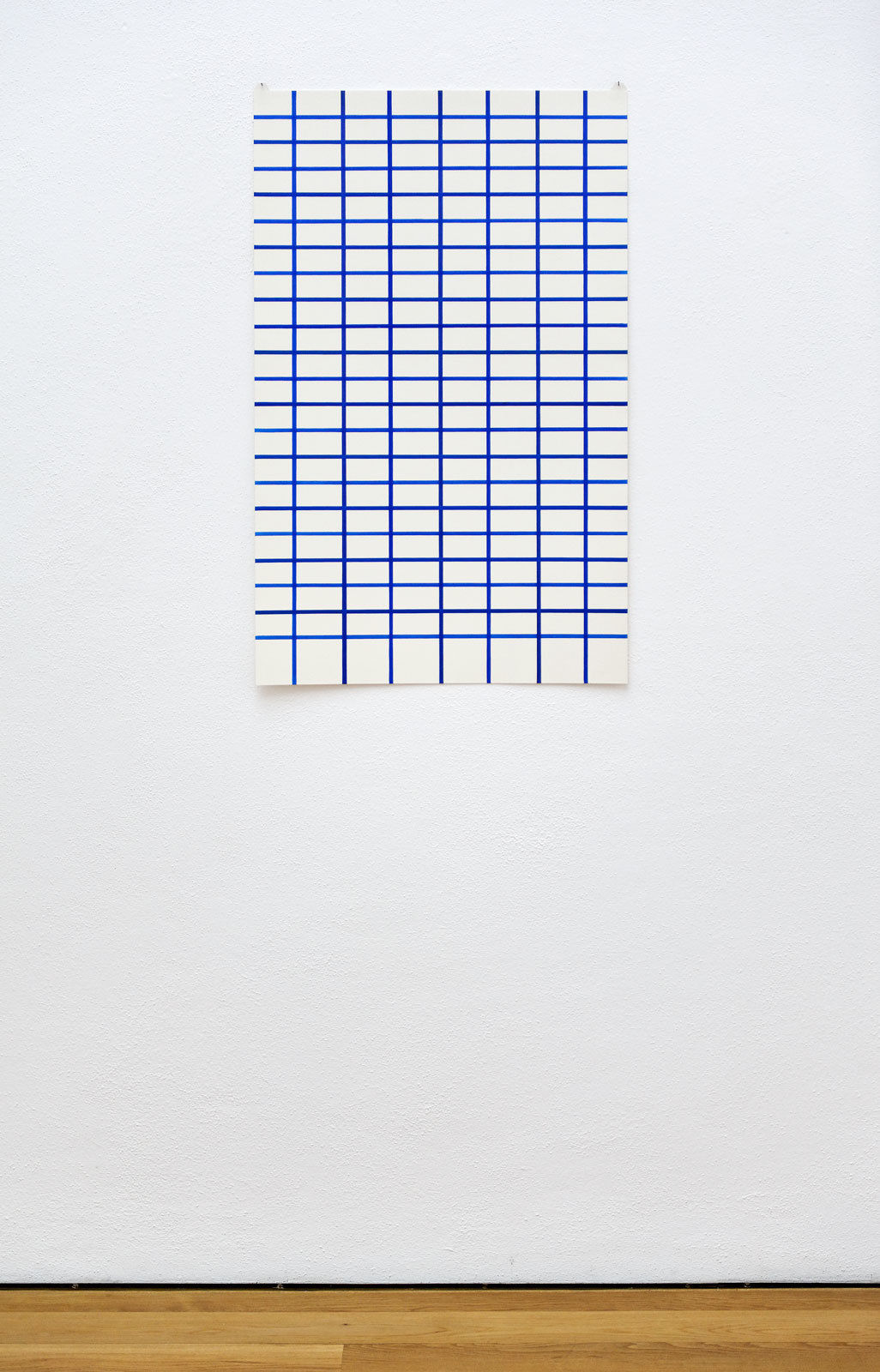

The opening-up and expansion of the concept of art found expression in currents of the 1960s. Thomas Bayrle and Peter Roehr, for example, dealt with phenomena of modern society and mass culture. Moving between fascination, cool observation and biting criticism, their works — composed of constantly repeating set pieces —appeared like a flicker of the consumer and commodity world. Similarly, Gerhard Richter used photographs as the point of departure for his paintings. He questioned the image as painting and, at the same time, as a reflection of our reality. For his work Terese Andeszka, he chose a photograph from a newspaper clipping that initially appears to tell the story of a private tragedy (with an ultimately happy outcome) but, in fact, refers to something larger, namely, to the division of Europe by the Iron Curtain and, thus, to Richter's own biography. This „truth, “ however, was concealed by Richter; it is only accessible via a „detour“ through his picture archive published as Atlas. It is there for the first time that we become privy to the full caption of the newspaper clipping that identifies the family in the photo as refugees from Hungary, putting their rescue suddenly in an entirely different context.

Two art prizes are associated with Museum Wiesbaden. The first is the Alexej von Jawlensky Prize of the state capital Wiesbaden, which commemorates the life's work of the great Russian painter, who lived in Wiesbaden from 1921 until his death in 1941. It is awarded every 5 years with the financial support of the Hessian state capital, Spielbank Wiesbaden, and the Nassauische Sparkasse, among others.

The second is the Otto Ritschl Prize. The artist lived in Wiesbaden from 1918 until 1976. After his early figural and, later, more Surrealist works, Ritschl began, in the 1950s, to move progressively toward geometric and, finally, more expressive abstraction. The increasingly meditative work of his late period, beginning in the early 1960s, focused on immaterial space, shaped entirely through color. The Museum Association Otto Ritschl began bestowing the prize in 2001 in Ritschl’s honor to keep the artist’s name alive.

Museum Wiesbaden offers a variety of programs for all ages, from guided tours to workshops for preschools and schools, to teacher training and programs for students, private groups, or families with children.