7 Mar 25 — 22 Jun 25

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Venus and Cupid as Honey Thieve, 1527, beech wood, 83 x 58,2 cm, Schwerin, Staatliche Schlösser, Gärten und Kunstsammlungen Mecklenburg-Vorpommern © bpk / SSGK M-V / Elke Walford

For the first time, this story is being told in an exhibition using top-class works of art. Never before has it been possible to experience the wide variety of roles played by the bee as vividly as in our exhibition. Surprising stories, instructive tales, philosophical ideas and astonishing allegories can be marveled at around this insect. Many of the stories are still touching today, because the bee has always been the inspiration for the visualization of general human feelings and ideals.

The exhibition presents the bee in art in eight chapters. Stories are told, such as that of the ancient god of love Cupid, who mutated into a honey thief, or the legendary feeding of Jupiter's boy with honey. There is also a wealth of symbols in which the bee plays the leading role. These include allegories of peace and anger as well as the virtues of diligence and patience. But the defensive nature of this insect has also been interpreted many times, as has the sweetness of honey or the fascinating structure of the bee colony.

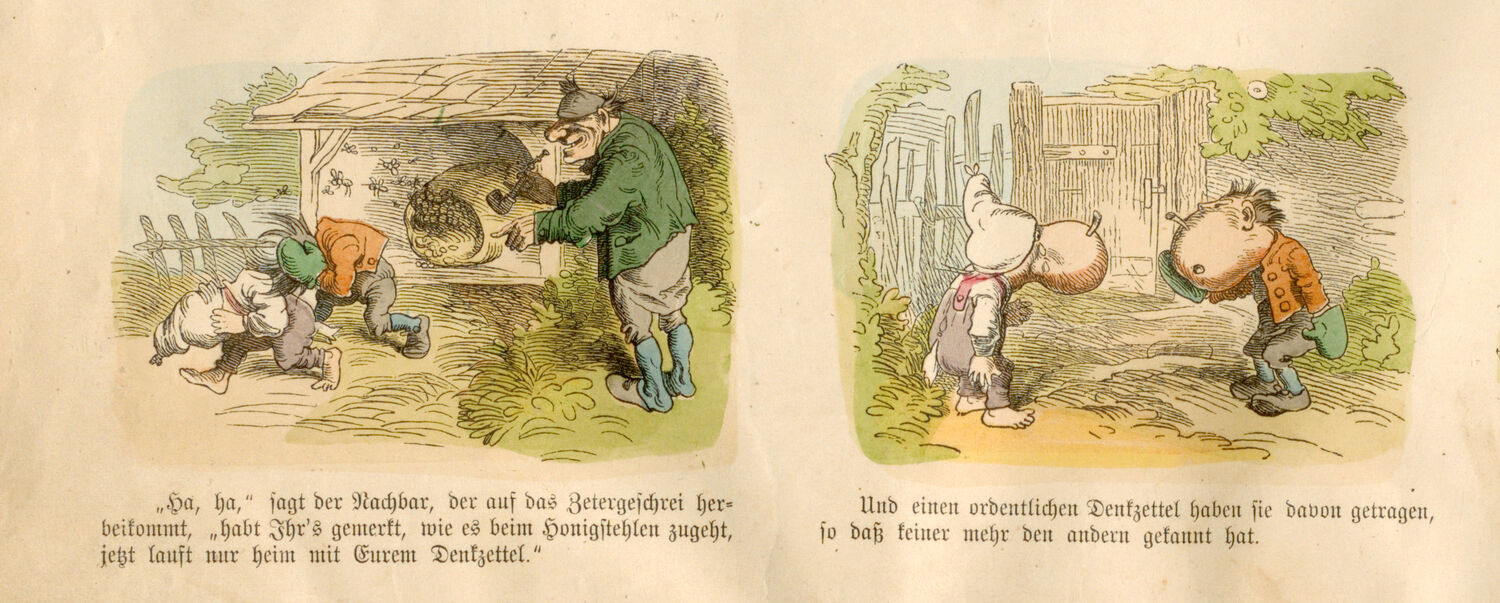

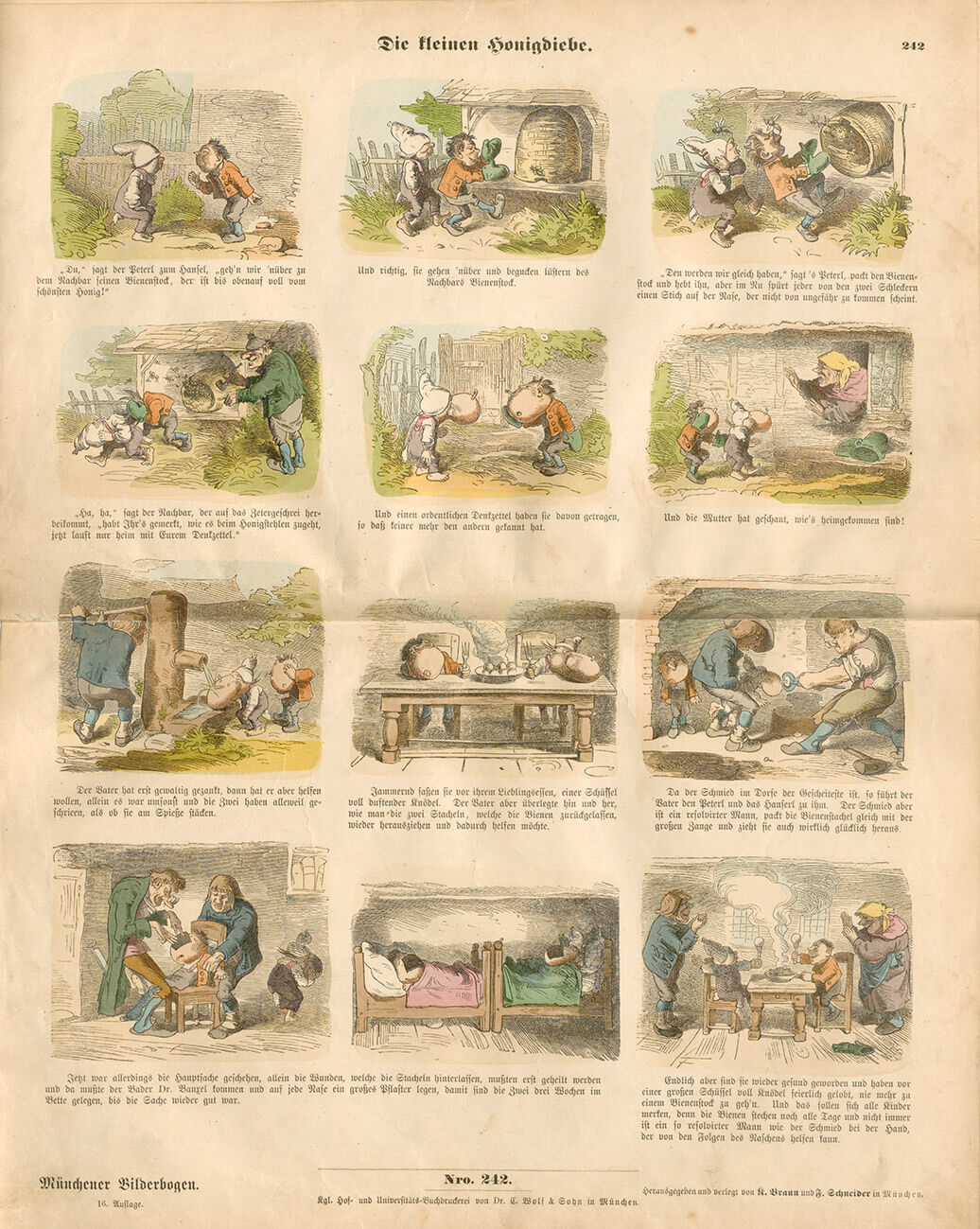

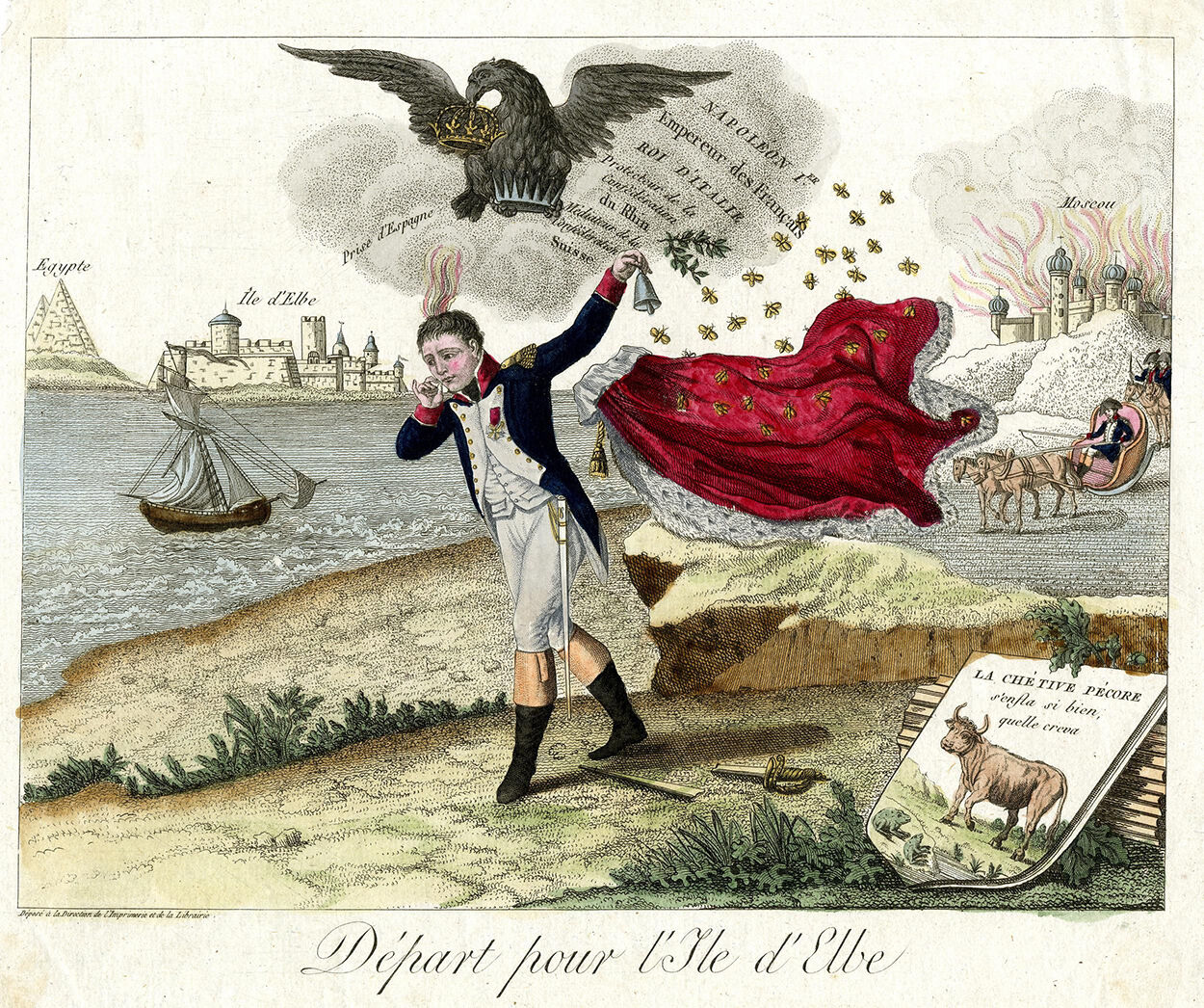

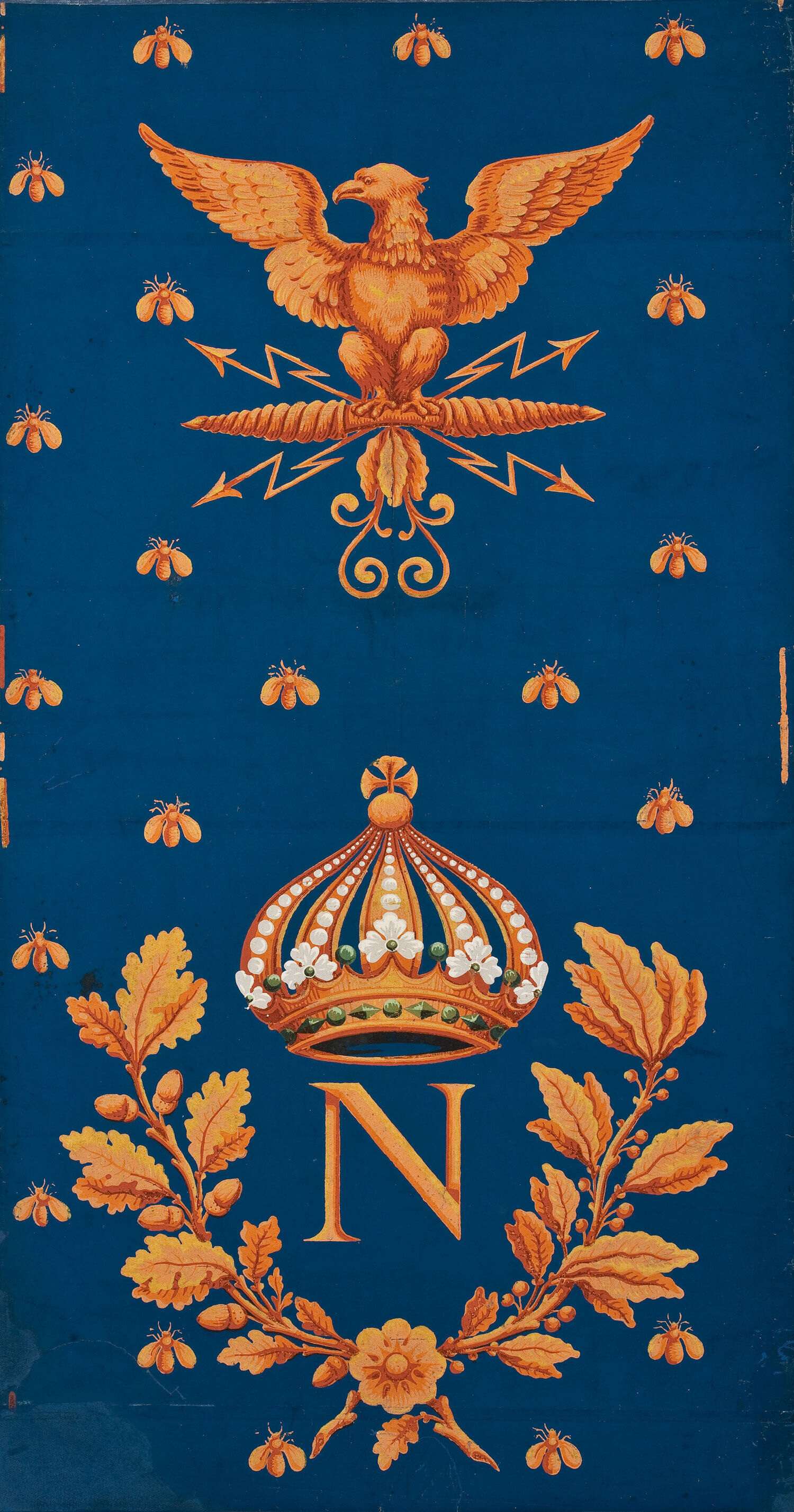

Whether as a symbol in Christianity or a symbol of general human considerations, whether as a preciously designed object of Baroque arts and crafts or in the ornamental beauty of Art Nouveau, the bee has a lot to tell us humans – and vice versa. That is why the exhibition also explains why Napoleon elevated the bee to an imperial symbol and what role the insect played in personal emblems. Of course, neither Wilhelm Busch's “Little Honey Thieves” nor Waldemar Bonsels' “Maya the Bee” are to be missed. Finally, the exhibition's parkour leads into selected positions of modern and contemporary art, including works by Joseph Beuys, Rebecca Horn and Stephanie Lüning.

The exhibition brings together more than 140 exhibits from seven centuries: paintings, sculptures, drawings, graphic art, caricatures, arts and crafts as well as medals and illustrated books. Among them are treasures from leading European museums as well as treasures from private collections, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, the British Museum in London, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the Musei Reali in Turin.

The perception of the bee in antiquity finds representation in the art of the early modern period. Many of the qualities that were associated with the bee in this era — such as diligence, a sense of community spirit, peaceableness, chastity, wisdom, and a capacity for self-defence — are still in use today. Honey was regarded as the nectar of the gods, with Jupiter’s childhood diet of milk and honey featuring as one of the most central myths. Furthermore, the Golden Age in Greek mythology was also characterised by streams of honey pouring forth from oak trees. Comparisons were also drawn between the social life of bees and that of humans, and the structure of the bee colony was applied to the structure of the Roman empire.

In the Christian tradition, the bee is also held in high regard. Today, the most well-known of these allegories is probably the prophecy of the land that flows with milk and honey, adopted in Morazzone’s painting “The Honey Madonna”. Just as well-known is Samson’s riddle “Out of the eater came forth food, And out of the strong came forth sweetness” (Judges 14:14).

The sweetness of honey was also seen as a parable for rhetorical skill, as illustrated in Saint Ambrose’s miracle of the bee, painted by Bergognone. Saint John’s prophecy on the Island of Patmos is also said to have tasted sweet like honey. Wax, on the other hand, was used in the church as an ingredient to make candles and for votive offerings due to the perceived chastity of bees.

![Philipp Galle after Jan van der Straet, Capturing Swarms of Bees, 1578, engraving, 21,2 x 28 cm (plate) © Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek (Sign. 39.1 Geom. 2° [1–47])](/en/assets/components/phpthumbof/cache/Wolfenbuettel_Galle_Detail_2.6edaba8ef6689d39fb7eb303d79b4cd4.jpg)

Between 30,000 and 70,000 (female) worker bees and 1,000 (male) drones form a long-lasting colony with their queen: a superorganism. And when it comes to the world of art, it is the honey bee (Apis mellifera) in particular that takes centre stage; its wild sisters seldom make an appearance.

Depictions of beekeepers were rare in art until the seventeenth century. One motif that appears rather often is the use of sound to capture a swarm of bees — a technique that was practised as far back as antiquity. In this section, you will also learn about aspects of beekeeping such as protective clothing, tools, pest control, and honey extraction.

While certain animals such as the meek lamb or the cunning fox are associated with only one character trait, the characteristics with which the bee is associated are numerous and at times contradictory. The bee is regarded as hard-working, helpful, tidy, chaste, docile, virtuous, wise, obedient, and invested in the common good, but also as both defensive and aggressive. The bee produces sweet honey, but its sting is painful. Its life is lived according to the principles of collaboration and equitable division of labour, yet it gathers around a queen.

The symbolism of the bee varies according to era and context and does not always correspond to current conceptions; nowadays, we tend to cast a critical eye on the anthropomorphisation of animals. Yet despite this, stories of the bee continue to enrich our world. In the fourth section you will be able to explore six thematic blocks: the pain of love, virtuousness, the four seasons, sense of taste, social bees, and the moral abyss.

The fifth section will take a look at some symbols that are used to represent individual characteristics. Filarete’s self-portrait medal — the oldest object in the exhibition — likens the bee to the artist: just as the bee produces its distinctive honey from a wide variety of flowers, so does the artist take in a wide range of inspiration in order to ultimately generate their very own distinctive artwork. The swarm of honeybees discovered by Samson in the corpse of a dead lion represents earthly strength, but also the immortality of the soul. The king bee, surrounded and admired by his subjects, symbolises claims to power, whereas a female monarch represents the bees’ fulfilment of their social duties by serving the common good. Under Pope Urban VIII, the bee became a popular symbol in the art world: the three bees featured on his coat of arms can be seen in every artwork he commissioned.

Now it is time to discover two illustrated fables about the bee written by Aesop, the legendary poet of antiquity. In one fable, he explains why the bee loses its life when it stings a human, and in the other, he contrasts the bee with the bear as a paragon of patience. In Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, the bee and the bear meet once again, this time within a parable about taking timely precautionary action. We find another confrontation in La Fontaine’s fable of the hornets and the bees, which serves an example of the prudent administration of justice. And finally, Wilhelm Busch’s “The Little Honey Thieves” and Waldemar Bonsel’s “Maya the Bee” take us into the long nineteenth century.

Although the boundaries between historical epochs are only constructs, they provide us with a certain clarity and economy. After the previous sections dedicated to the Early Modern Era (15th — 18th Century) the exhibition continues with the so-called “long nineteenth century”. The middle class of the day adopted a number of existing allegories associated with the bee, including the story of Cupid the honey thief and the bee as a symbol of industriousness. The notion of the beehive as an idyllic place, on the other hand, is specific to the time, and arose as a kind of antithesis to the era’s rampant industrialisation and urbanisation. Hans Thoma’s “The Bee Friend” is emblematic of this new trend in symbolism, the roots of which can be traced back to the golden age of antiquity.

Napoleon adopted the bee as his personal emblem, while England used the image of the beehive to represent the constitutional monarchy. The bee also established itself as a popular element of jewellery — both as an ornamental emblem of Napoleon and as a motif of Art Nouveau.

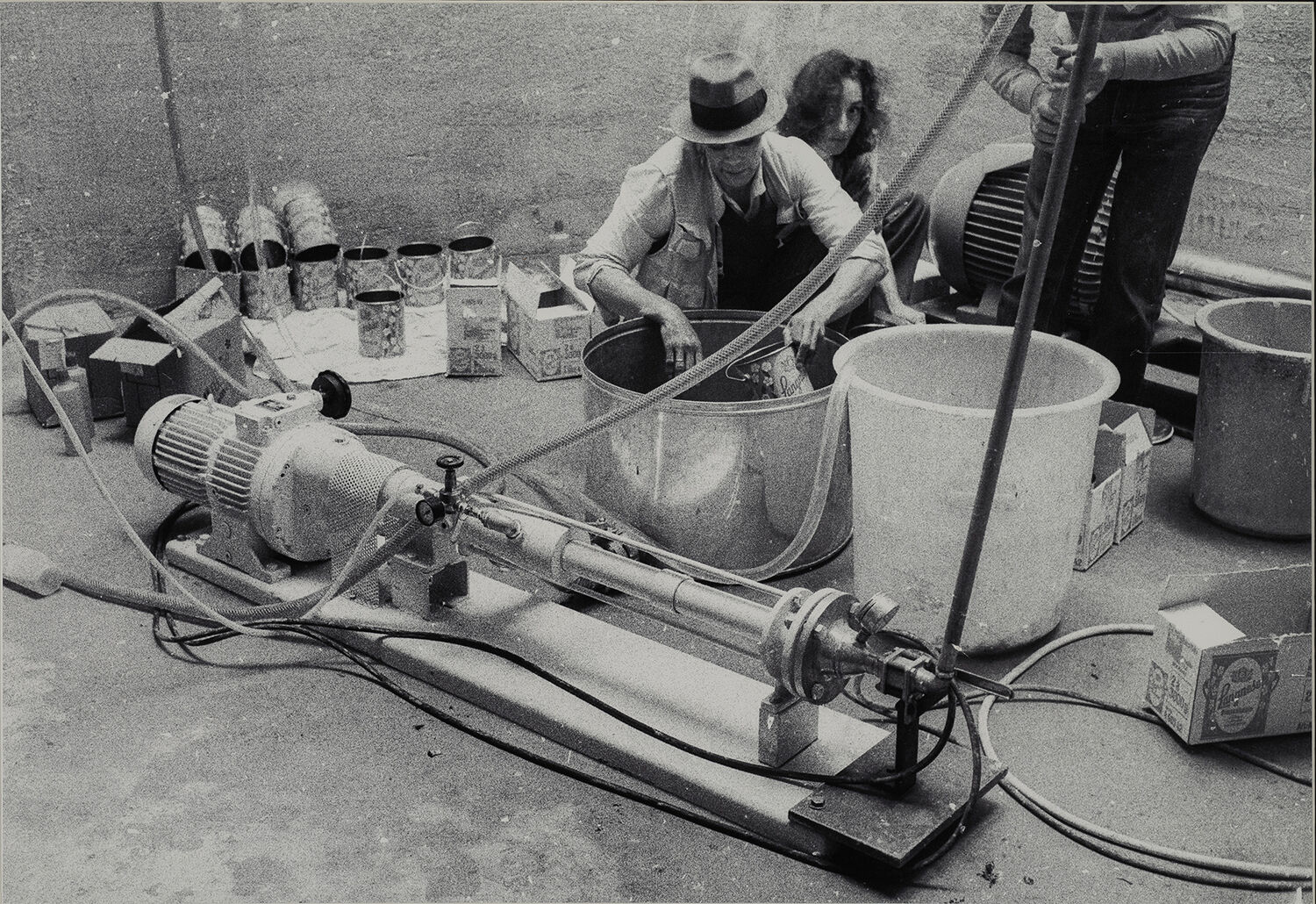

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the bee barely played a role in art. This changed, however, in the latter three decades of the century, when artists began to explore the use of wax and honey as materials in their art and to investigate the social behaviours of bees. To conclude the exhibition, we will now present a selection of such artworks that touch on the themes of this exhibition.

In 1977, Joseph Beuys initiated a site for discussion at documenta 6 with his piece Honey Pump at the Workplace. For him, honey was a living substance, which he understood to be analogous to living thought. Stephanie Lüning’s wax casts are moulded by flowing water, while Lea Grebe explores the processes that take place inside a beehive. Aladin Borioli traces the tradition of the Bannkorb or charm basket, which was used to ward off evil spirits, and Rebecca Horn’s spatial installation raises a number of important questions, such as our own individual responsibility for the bee population.

The exhibition is a feast for the eyes. It is a must for all bee fans, young and old. Anyone interested in art and cultural history will also get their money's worth. The exhibition is signposted throughout in German and English. An entertaining tour in the free MuWI app presents ten selected highlights.

Guided tours, lectures, readings and other events can be found in the calendar. We offer a wide range of guided tours, workshops and other formats for nursery and school groups, families and private groups. An entertaining tour in the free MUWI-App presents ten selected highlights.

Two cooperation partners invite us to their parks so that we can observe the bee as a living being: The State Palaces and Gardens of Hesse and Schloss Freudenberg.

ALL EVENTS ARE IN GERMAN

MUSEUM WORKSHOP FOR CHILDREN

Sat 15 Mar, 26 Apr & 31 May, each 10:15—13:00

LECTURE

Thu 27 Mar, 19:00

Clear the stage for the bee — or A stage for the bee

read by Armin Nufer, actor and speaker, Wiesbaden

FILM

Sun 6 Apr, 17:30

More than Honey — A film by Markus Imhoof, 2012

At the Filmtheater Caligari, info and tickets

LECTURE

Thu 15 May, 19:00

Don't get caught heretic!

The enigma of Pieter Bruegel the Elder's beekeeper drawing

With Prof. Dr. Jürgen Müller, Institute for Art and Musicology, TU Dresden

READING

Thu 22 May, 19:00

The song of honey. A cultural history of the bee

presented by Ralph Dutli, writer, Heidelberg

SUMMER FESTIVAL

Sat 14 Jun

FREUDENBERG CASTLE

Sat 26 Apr, 31 May & 14 Jun, each 15:00—17:00

Honey yellow — encounters with bees in the Freudenberg Castle and Park field of experience

Information and registration: kontakt@schlossfreudenberg.de, 0611 ⁄ 4110141

1 Hans Thoma, The bee friend, 1863, oil on canvas, 62.5 × 50.5 cm © Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

2 attributed to Hendrik de Keyser, 1565–1621, Crying Child, engraved by a Bee, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Netherlands

3 Lucas Cranach the Elder, Venus with Cupid as Honey Thief, 1527, Schwerin, State Palaces, Gardens and Art Collections Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

And even more bees: The Museum Wiesbaden is the Hessian State Museum for Art and Nature, and we are delighted to be able to show you another exhibition on bees in parallel in the Natural History Collections: “Honey yellow – The Bee in Nature and Cultural History” (7 Mar 2025 — 8 Feb 2026).