The museum’s Classical Modernism collection holds international significance, above all, for its assemblage of over 100 works by Russian Expressionist Alexej von Jawlensky (1864—1941), who spent the last twenty years of his life in Wiesbaden.

The complex of works by the artist Alexej von Jawlensky, who lived in Wiesbaden from 1921 until his death in 1941, is one of the major focal points of Museum Wiesbaden today. The museum’s initial collection of Jawlensky works, built up in the late 1920s and early 1930s, was purged entirely between 1933 and 1937, as a result of National Socialist cultural politics. All of the works in the museum’s initial collection were either returned to their previous owners or removed from the premises. The museum’s Jawlensky collection today has been rebuilt through strategic acquisition over the last 25 years and now encompasses over 111 works, making it, alongside the holdings of the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, one of the largest and most significant Jawlensky collections worldwide.

The works in this collection represent all of the major phases of development in the artist’s career — the early Munich period, the Murnau and Schwabing period, exile in Switzerland and the formative Wiesbaden years. Moreover, the collection contains a number of his multifaceted graphic works of exceptional quality, including self-portraits, portraits, and landscapes.

In 2021, on the occasion of the commemorative exhibition The Lot! 100 Years of Jawlensky in Wiesbaden, Marian Stein-Steinfeld (granddaughter of Hanna Bekker vom Rath) donated to the museum the correspondence, containing 40 letters, between the artist and his patron Hanna Bekker vom Rath.

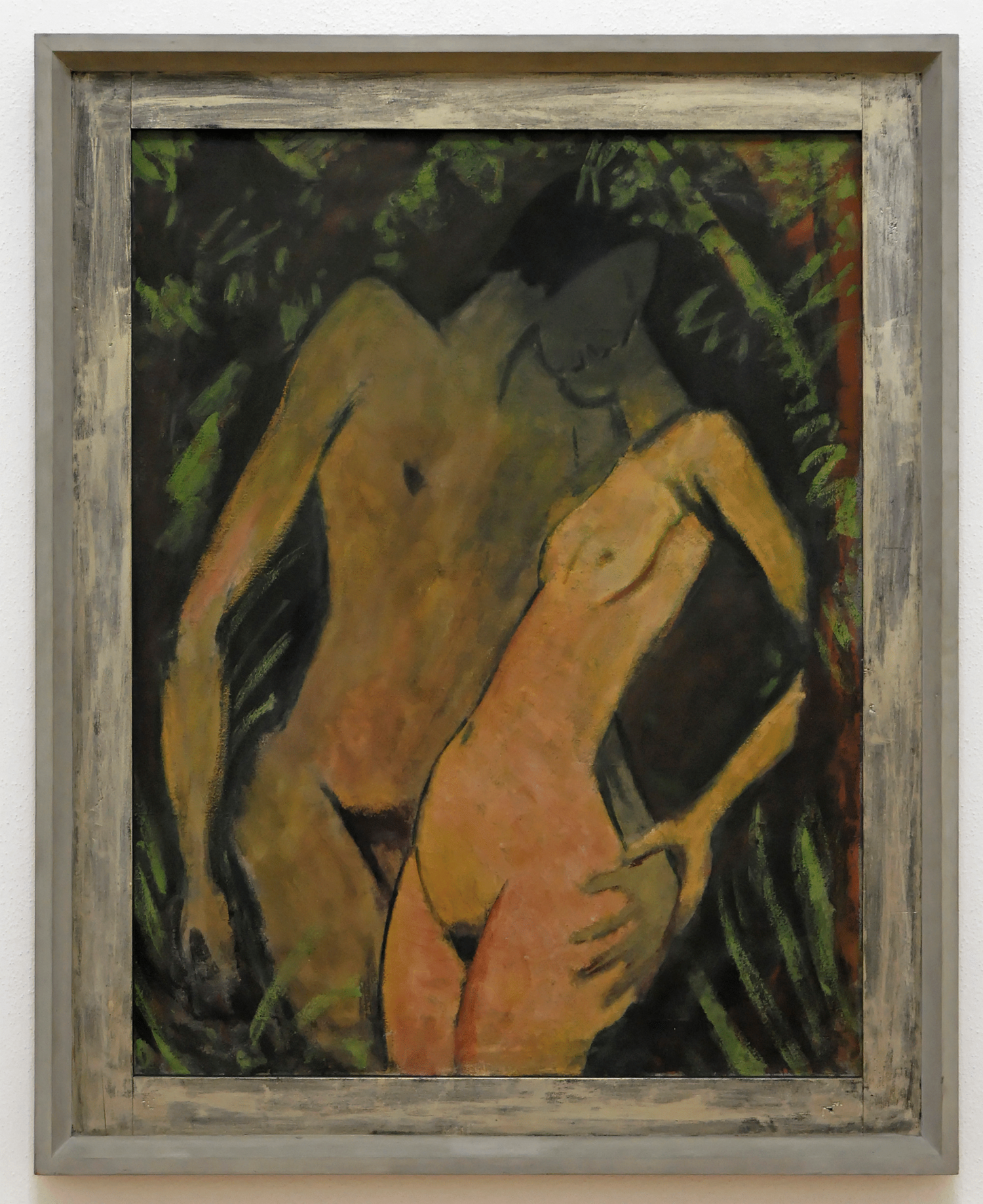

The significance of the museum’s Classical Modernism collection was augmented in 1987 with the addition of the Hanna Bekker vom Rath collection, containing works by such noted Expressionists as Ernst Barlach, Lovis Corinth, Lyonel Feininger, Natalia Gontscharowa, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Otto Mueller, and Emil Nolde, as well as major works by Willi Baumeister, Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In addition to the important Expressionists Ernst Barlach, Lovis Corinth, Lyonel Feininger, Natalia Goncharova, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Otto Mueller, and Emil Nolde, major works by Willi Baumeister, Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, among others, were added to the collection through this groundbreaking acquisition in the late 1980s.

The acquisition is inextricably linked to the name of the collector and art dealer Hanna Bekker vom Rath, whose “blue house” in Hofheim in Taunus served as a refuge for many artists labeled “degenerate” by the Nazi regime. Some 30 highly valuable paintings and drawings were purchased from her estate by the Society for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Wiesbaden and made available on permanent loan to Museum Wiesbaden.

By contrast to the Jawlensky collection, there was little expansion to the museum’s Constructivist focus in the 1950s. It was not until the 1990s that genuine expansion occurred when the Vordemberge-Gildewart Foundation in Switzerland bequeathed its vast archive of the Constructivist artist’s works to Museum Wiesbaden. Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart (1899—1962), who in the 1920s was invited by Theo van Doesburg himself to become a member of the de Stijl group, left behind an estate encompassing some 50 000 drawings, typographic works, studies, and guest books, as well as numerous sketches, photos, letters, and other papers belonging to his circle of friends and acquaintances, such as Kurt Schwitters, László Moholy-Nagy, and Theo van Doesburg. The bequeathal of this extensive material has made Wiesbaden one of the most important sites of Constructivism in Germany.

Two art prizes are associated with Museum Wiesbaden. The first is the Alexej von Jawlensky Prize of the state capital Wiesbaden, which commemorates the life's work of the great Russian painter, who lived in Wiesbaden from 1921 until his death in 1941. It is awarded every 5 years with the financial support of the Hessian state capital, Spielbank Wiesbaden, and the Nassauische Sparkasse, among others.

The second is the Otto Ritschl Prize. The artist lived in Wiesbaden from 1918 until 1976. After his early figural and, later, more Surrealist works, Ritschl began, in the 1950s, to move progressively toward geometric and, finally, more expressive abstraction. The increasingly meditative work of his late period, beginning in the early 1960s, focused on immaterial space, shaped entirely through color. The Museum Association Otto Ritschl began bestowing the prize in 2001 in Ritschl’s honor to keep the artist’s name alive.

Loading …

We are already planning new dates for this event! In the meantime, check out our calendar to see other exciting offers.

Museum Wiesbaden offers a variety of programs for all ages, from guided tours to workshops for preschools and schools, to teacher training and programs for students, private groups, or families with children.